Inciting Democracy: A Practical Proposal for Creating a Good Society

Chapter 2:

Elements of a Good Society

Download this chapter in pdf format.

In This Chapter:

What would a “good society” look like?

Since every person has her own definition of a good society, there cannot be a single, universal standard — there are at least as many definitions as there are people. Only in a dictatorship could one person unilaterally decide what constituted the elements of a good society and impose this definition on others. Certainly, most people would agree that having one person dictate to everyone else is not acceptable in a good society.

However, this point does indicate one area of agreement: most people probably concur that a good society must be responsive to the people who live in that society. Further, most people probably agree that a good society must be an amalgam of everyone’s best ideas. Hence, the first element of a good society must be rudimentary democratic consent: everyone must at least passively accept how the society is constituted and agree that it basically conforms to their own conception of a good society.

The good of the people is the highest law.

I also believe virtually everyone can endorse the principle of the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” A good society would treat every human being in the same way each of us would like to be treated — with fairness, kindness, consideration, forgiveness, support, generosity, and love.[1] From this fundamental principle, there are several basic elements that most people would readily agree must be present in a good society. These are described below.[2] The next section then lists a few additional elements that I believe also follow from the Golden Rule and belong in a good society though they currently are not as widely endorsed. Of course, the actual good society that would emerge from progressive transformation would be determined by everyone using consensual procedures.

Appendix A lists some specific, near-term policy changes that could begin the shift toward a good society.

Basic Elements of a Good Society

Rudimentary Democratic Consent

In a good society, everyone must at least passively endorse the basic structure. At a minimum, everyone must agree that the primary elements are configured in a sensible and just way.*

* I hope that in a good society, people’s consent would be far stronger. Preferably, the vast majority would feel that most aspects of the society were not only reasonable, but actually desirable — they would not just tolerate their society, but actually like it.

Universal Access to Human Essentials

Every human being requires certain things to live: air, water, food, protection from harsh weather (clothing and shelter), and safety from harm. In a good society, everyone would have her basic human needs met.

If there are homeless people on the streets while rooms in mansions sit empty, we do not have a good society.

If children go hungry while others eat, we do not have a good society.

If some are idle while others work too much, we do not have a good society.

This seems elementary, but some philosophers and politicians have argued that satisfying everyone’s basic human needs is not critical. They argue that some greater virtues can only be achieved by allowing or forcing some people to be destitute. They value these greater goods more than universal access to necessities.

But these thinkers are almost never themselves lacking essentials, and they do not offer to relinquish them for others. In stark contrast, those people who are destitute almost never believe they live in a good society — their definition requires that they rise out of poverty. Clearly, everyone needs the basics and a society that does not provide them is not very good.

Access to Other Desirable Items

I’m not at all contemptuous of comforts, but they have their place and it is not first.

There are other basics that nearly everyone desires: tasty food, comfortable housing (with furniture, running water, and electric lights), transportation, a clean and healthy environment, healthcare, meaningful work, regular exercise, rejuvenating leisure, fulfilling relationships, family, and a close-knit community. People also want material goods like basic household appliances (such as a stove, refrigerator, kitchen tools, broom, vacuum cleaner, washing machine, clothes dryer, bathtub, shower), other basic items (like paper, pencils, books, magazines, newspapers, a bicycle), and luxuries (like an automobile, television, VCR, sound system, and a computer). People also desire good literature, music, theater, poetry, sculpture, and the other arts.

None of these is essential, but life without at least a few of them is not much fun.* To me, a good society would enable most people to have most of the basic desirable items and would allow everyone to have at least a few luxuries.

* Some of these items may seem essential, but consider what you would be willing to relinquish if it meant that a loved one could have enough to eat. Forced to make such a choice, all of these items would clearly be desirable, but not essential.

Society Out of Balance

Work

- In 1998, the average full-time worker in non-agricultural industries worked an average of 3.1 hours overtime per week — the equivalent of about 7.0 million full-time jobs.[3] In the same year, there were 6.2 million unemployed people.[4]

- The typical American worker worked 163 hours more in 1987 than in 1969 — the equivalent of one month more.[5]

- Every European economy except Italy and the United Kingdom requires employers to offer annual paid vacations to their workers of from four to six weeks. The United States requires none. U.S. workers average just over three weeks of paid vacation.[6]

- In 1990, Americans spent an average of 3.7 hours just commuting to and from work each week.[7]

Motor Vehicle Accidents

- In 1997, there were 13.8 million serious motor vehicle accidents in the United States, which killed more than 43,000 people. More than 6 million people were injured.[8]

Poverty and Homelessness

- In 1999, despite record employment, 32.3 million people (11.8 percent of the total U.S. population) lived in poverty. This included 11.5 million children under age eighteen (16.3 percent of all children). The poverty rate for African Americans was 23.6 percent. The poverty rate for American Indian and Alaska Natives was 25.9 percent.[9]

- “Even in a booming economy, at least 2.3 million adults and children, or nearly 1 percent of the U.S. population, are likely to experience a spell of homelessness at least once during a year.”[10]

Poor Health Coverage

- In 1999, despite record employment, 42.6 million people (15.5 percent of the total U.S. population) did not have health insurance. This included 10.0 million children under age eighteen (13.9 percent of the total). Nearly one-third of Hispanics were uninsured.[11]

- The World Health Organization (WHO) reports “the U.S. health system spends a higher portion of its gross domestic product than any other country but ranks 37 out of 191 countries” in overall performance.[12]

Freedom and Liberty

In a good society, seldom would anyone be dominated, oppressed, or thwarted by another person or group. Whenever someone was oppressed, most everyone else in the society would immediately work to end her oppression. People would also be free from intrusion into their private behavior. People would be free to think, do, and believe whatever they wanted as long as it did not hurt others.

The ultimate end of all revolutionary social change is to establish the sanctity of human life, the dignity of man, the right of every human being to liberty and well-being.

Of course, in any society where people live near one another and interact, they will inevitably conflict with each other. However, in a good society, people would do their best to stay out of each other’s way. When people did conflict, they would use rational debate, appeals to conscience, mediation, nonviolent struggle, amiable separation, or other conflict resolution measures to resolve their differences.

In a good society, children would learn to respect others and would learn how to restrain themselves from hurting others. They would also learn how to work together cooperatively and to resolve conflicts graciously so that, when they grew up, their conflicts would be minimal.

Still, in a few cases, people’s freedom and liberty must be restricted. There must be some way to prevent those who have transgressed against others from doing it again — methods like required emotional counseling, jail, or banishment. But these methods must be used sparingly and employ a bare minimum of force so as not to harm or dehumanize the transgressors.

Equity and Fairness

If women are afraid to walk outdoors at night, we do not have a good society.

If dissenters fear speaking out, we do not have a good society.

Life is not fair and there is no way for a society to be completely equitable. But to me, a good society cannot be grossly imbalanced, and it certainly would not encourage or allow anyone to prosper at the expense of others through fraud, deception, corruption, intimidation, domination, or oppression.[13]

In a good society, everyone would at a minimum have equal access to information, resources, and opportunities. As much as possible, everyone would also have roughly the same amount of the material goods listed above, and no one would have significantly more than anyone else. How much is “significantly more” would, of course, need to be determined by everyone in society — again, everyone must give rudimentary consent. The methods used to ensure equitable distribution (investigation, reporting, regulation, enforcement) must also use a bare minimum of force so as not to harm anyone.

Society Out of Balance (continued)

The Environment

- The United States represents 5 percent of the world’s population and uses 26 percent of its oil. In contrast, India has 16 percent of the world’s population and uses 3 percent of its oil.[14]

- In 1998, about 40 percent of U.S. streams, lakes, and estuaries that were assessed by the EPA were not clean enough to support uses such as fishing and swimming.[15]

- Eleven of the world’s fifteen most important fishing areas are in decline and 60 percent of the major fish species are either fully or over- exploited.[16]

- On average, U.S. children eat a combination of twenty different pesticides daily.[17]

- Nearly 46 percent of the nation’s federally subsidized apartments (870,000 units) are within a mile of factories that produce toxic pollution.[18]

Voting

- In the November 1996 presidential election, only 49.0 percent of adults voted. In the November 1998 federal election, only 32.9 percent of adults voted.[19]

Foreign Policy

- The United States has not signed a number of human rights treaties signed by most other countries of the world. These include:

-

- International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

- Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women

- Convention on the Rights of the Child[20]

Environmental Sustainability

Humans have evolved for thousands of years closely linked to nature. We are adapted to the earth’s environment and can live quite well in it. A good society would mesh seamlessly with the natural environment, maintaining and supporting natural systems. We would live in consonance with all other species.

Balance

There are unavoidable conflicts in society — conflicts between self-interest, the common good, the natural environment, privacy, personal liberty, and equity. Differences invariably lead to conflicts. For example, there will always be some people who want to engage in behavior that others find lewd or disgusting. A good society would balance everyone’s interests and resolve these inherent conflicts in ways that a sensible person would find acceptable.

Don’t judge a person until you have walked a mile in his moccasins.

For example, the right of people to make loud sounds (music, construction noise, and so on) must be balanced against the needs of others for quiet. A sensible solution would allow anyone to make as much sound as she wanted when no one else was around, a certain amount of sound during the daytime when others were not likely to be bothered, and very little during the night when others were sleeping.

Similarly, people could engage in any kind of private behavior they wished as long as it did not hurt anyone else. However, in public, society might expect them to stay within certain bounds. Society might also try to limit self-destructive private behavior (like riding a motorcycle without a helmet or smoking tobacco) that would ultimately affect the society (when they needed medical care to treat their accident or illness).

In like manner, a good society would fashion a balance between the inherently conflicting needs of people for stimulation and relaxation, sensuality and propriety, spontaneity and deliberation, impulsive drive and caution, indulgence and moderation, exhibition and modesty. A good society would also reconcile end values with process values (such as justice with compassion) and would reconcile conflicting process values (such as democracy and expediency, acceptance and dissent).

Forging a sensible balance is difficult, but is almost always possible when undertaken by people of goodwill.

Society Out of Balance (continued)

Childrearing

- The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children be breastfed for at least a year. However, in 1995, only 59.4 percent of women in the United States were breastfeeding at the time of hospital discharge, and only 21.6 percent were still nursing six months later.[21]

- “87% of parents of children aged two to seventeen feel that advertising and marketing aimed at children makes kids too materialistic.” Also, “almost half of all parents report that their kids are already asking for brand name products by age 5.”[22]

Firearms

- There are approximately 192 million privately owned firearms in the U.S. — 65 million of which are handguns.[23] An estimated 39 percent of households have a gun — 24 percent have a handgun.[24]

- The overall firearm-related death rate among U.S. children under age fifteen is nearly twelve times higher than among children in twenty-five other industrialized countries.[25]

Prisons

- In 1999, there were 1.3 million people in state and federal prisons — more than five times as many as in 1970. An additional 606,000 people were held in local jails.[26]

- In 1997, there were 5.7 million adults in prison or jail, on probation, or on parole — about 2.9 percent of the total adult population.[27]

- The 1999 United States’ rate of incarceration of 682 inmates per 100,000 population was the second highest reported rate in the world, behind only Russia’s rate of 685 per 100,000 for 1998.[28]

- If incarceration rates recorded in 1991 continued unchanged in the future, an estimated 5.1 percent of all persons in the United States would be confined in a state or federal prison during their lifetime. A man would have a 9.0 percent chance of going to prison during his lifetime, a black male greater than a 1 in 4 chance, an Hispanic male a 1 in 6 chance, and a white male a 1 in 23 chance.[29]

Additional Characteristics of a Good Society

What I mean by Socialism is a condition of society in which there should be neither rich nor poor, neither master nor master’s man, neither idle nor overworked, neither brain-sick brain workers nor heart-sick hand workers, in a word, in which all men would be living in equality of condition, and would manage their affairs unwastefully, and with the full consciousness that harm to one would mean harm to all — the realization at last of the meaning of the word commonwealth.

Beyond these basic elements, I imagine a good society would also be:

Humane and Compassionate

People and institutions would be sympathetic towards, appreciative of, and considerate of other people, other species, and the overall environment. The primary goal of the society would be to support all people to live enjoyable lives and to achieve their full potential as human beings. Human welfare would take precedence over money, property, and power. Society would generously offer extra help to those who had suffered from disability, poor upbringing, illness, injury, or some other misfortune. Society would also encourage altruism and cooperation.

Democratic and Responsible

As part of their everyday daily lives, people would have permission, would be encouraged, and would actually be active participants in governing and controlling all aspects of their society — political, economic, social, and cultural. It would be a society truly of the people, by the people, and for the people. No person or group would dominate decision-making.

Democracy is not a spectator sport.

The society would value citizen involvement and would try to inform, educate, and empower each person to be a full participant in societal decision-making. Everyone in society would be encouraged and expected to take personal responsibility and initiative, not only for themselves but for the whole society — each person obligated and entrusted to look out for the common good and to set right anything that was amiss. Moreover, this responsibility and care would not be limited to a citizen’s particular neighborhood, city, state, or nation, but would extend to the whole world. People would consider themselves global citizens.

To support democracy and responsibility, society would encourage people to be truthful and deal with each other in an honest and straightforward fashion. To further make democracy possible, society would also encourage people to work to heal their internalized emotional problems and overcome their fears and addictions.

Moreover, all the main institutions of society (government, schools, business, news media) would be responsive to the people in the community (not responsive only to shareholders). These institutions would treat people not just as voters, taxpayers, consumers, or spectators but primarily as citizens who ultimately “own” their society. As citizens, people have the right to be treated well and supported by all institutions. Moreover, as citizens, people have the right to know the truth about all aspects of society.

World Imbalances

From Human Development Report, 1999, United Nations Development Programme:[30]

- In 1997, the richest 20 percent of the world’s population had an annual income that was 74 times that of the world’s poorest 20 percent, up from 30 times as much in 1960. The most affluent 20 percent of the population of the planet consume 86 percent of the total goods and services in the world. The poorest 20 percent consume about 1 percent. [p. 3]

- In the past four years, the world’s 200 richest people have seen their net worth double to $1 trillion. Meanwhile, the number of people surviving on less than $1 a day has remained unchanged at 1.3 billion. [pp. 37, 28]

- In 1998, the top 10 companies in telecommunications controlled 86 percent of this $262 billion global market. The top 10 companies in pesticides controlled 85 percent of this $31 billion global market. [p. 3]

- “In 1995 the illegal drug trade was estimated at 8% of world trade, more than the trade in motor vehicles or in iron and steel.” [p. 5]

- “The traffic in women and girls for sexual exploitation — 500,000 a year to Western Europe alone — is one of the most heinous violations of human rights, estimated to be a $7 billion business.” [p. 5]

- “At the root of all this is the growing influence of organized crime, estimated to gross $1.5 trillion a year, rivalling multinational corporations as an economic power.” [p. 5]

- In 24 countries, life expectancy is estimated to be equal to or exceed 70 years, but in 32 countries life expectancy is less than 40 years.[31]

Tolerant and Wise

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain Unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

A good society would value the wisdom of every person. Every decision-making institution would invite a wide range of perspectives and truths. Society would encourage people to be respectful, tolerant, and understanding of others. Society would value dissent and diversity. Schools and other institutions would not teach people to be docile or to accept dogma and authority passively, but instead would encourage them to be creative and flexible and to think rationally for themselves.

Furthermore, people would be encouraged to challenge conventional wisdom whenever they believed it was outmoded. Societal norms would also encourage people to open themselves to other beliefs and perspectives and to let go of their own limited or obsolete ideas. People would be guided and helped in their efforts to resolve their conflicts without resort to physical violence, threat, or attack and with a minimum of social coercion. The society would have sensible mechanisms for rationally sorting out different perspectives and disseminating the distilled wisdom to everyone, especially to young people. As a result, individuals would continually learn and grow, and society would steadily improve.

Freedom rings where opinions clash.

Fun

In a good society where everyone’s basic needs were met, people could devote time to endeavors such as music, theater, art, adventure, travel, and self-education. Instead of narrowly focusing on work and constantly rushing around, they could contemplate truth and beauty, they could develop their creativity, and they could build close relationships with others.

A good society would allow and encourage people to live exciting and joyful lives. Secure and unafraid, people could be as passionate, playful, outrageous, and funny as they wanted to be. Every day, people would sing, paint, dance, write poetry, explore, lie under trees, play with children, and gaze at the stars.

A good society enables and encourages everyone to practice her best behavior.

Overall, I imagine that in a good society, people would labor out of their love for their fellow human beings and for the joy they derived from tackling difficult challenges, they would play because it’s fun, and they would laugh for no reason at all.

Lessons from Young Children

Young children are energetic and joyful. There is much we can learn from them.

- What if we enjoyed exuberant play every day, exercising and feeling our body strength — walking, running, skipping, bicycling, skating, dancing, hiking, skiing, swimming — without trying to compete with anyone else?

- What if we spent time each day exploring, investigating, and making sense of our world?

- What if we spent time each day making silly statements, telling jokes, and laughing with our friends?

- What if we spent time each day cuddling with our friends?

Not Paradise

The good society described here may seem like a blissful paradise, completely free of suffering or discord. However, as noted in the Preface, there will always be conflict and pain in this world — we cannot escape the realities of life. Still, in the good society I envision, people’s difficulties and sorrow would be greatly reduced and their love and joy would outshine their woes and disputes. It would be a far more productive and pleasant society than our current one.

A Comprehensive Mix of Four Components

Achieving a society with these positive characteristics does not require perfection. Rather, a good society needs only a comprehensive mix of these four components:

- Individuals who are (1) educated and informed enough that they understand their connection and responsibility to others, and (2) emotionally healthy enough that they generally act well and seldom behave in irrational or destructive ways.

- A culture that largely promotes socially responsible behavior such as honesty, cooperation, tolerance, altruism, nonviolent conflict resolution, and self-education.

- Structures of incentives — rewards, penalties, and forms of accountability — that ensure people generally find it in their best interest to behave well.

- Institutions (political, economic, and social) that promote education, individual emotional health, and a socially responsible culture, and that implement structures of incentives for positive behavior.

These components can be incomplete and imperfect, as long as together they are sufficiently positive to offset their flaws and reinforce the best in the other components.

Examples of a Good Society

Based on these principles, what would a good society look like?

Reporter: Mr. Gandhi, What do you think of Western Civilization?

Mr. Gandhi: I think it would be a good idea!

Fortunately, dreamers and visionaries have thought about this a great deal. There are many books and articles with innovative ideas about particular aspects of a good society and several novels that depict comprehensive visions of desirable societies.* Though some of these visions are ridiculous, some are truly sensible and practical. Many of the ideas have been tried successfully on a small scale.

* See Chapter 12 for a list of visionary books.

Below, I describe in general terms how a few important institutions might look in a good society and how society might deal with some age-old problems. Please view these descriptions only as tentative examples. Invariably, as society improves, people will come up with better ideas.

Family, Children, and Social Interaction

If suicide and depression are common, we do not have a good society.

Since humans are social beings and need warm affection every day, in a good society most people would live in close connection with others. Many would live in traditional extended families (children, parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles under one roof or living close by). Others might live in configurations more common today: nuclear families (children and one or two parents), same-sex partnerships, co-housing, cooperative households, and communes. Others might even try unusual arrangements like group marriage or line marriage.[32] Some people would live alone. But everyone would have many ways to connect intellectually, emotionally, and physically with other people whenever they wanted.

To best provide for children’s needs, they would generally live in some configuration where many able adults provided nurturance, guidance, and support (in contrast to today’s single-parent and nuclear families where there are only one or two adults). By having many adults around, children would receive more attention, support, and affection, and they could learn from many approaches to life. All adults in the household would be encouraged to take on a proportional share of parenting responsibility, and they would have time in their lives to do this.

Unbearable Lives

- Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, and is the third leading cause of death for young people aged 15–24.

- Suicide took the lives of 30,535 Americans in 1997 (11.4 per 100,000 population).

- From 1952 to 1995, the incidence of suicide among adolescents and young adults nearly tripled.

— Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[33]

Parents and other adults who spent time with children would be taught the basics of compassionate childrearing including essential skills like how to change diapers, interpersonal skills such as counseling someone through grief, and parenting skills like how to teach and guide an inexperienced child. In addition, they would be coached by more experienced elders such as grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Trained counselors in each community would provide additional therapy and support to children or adults in distress. Conflict resolution facilitators would offer mediation for parent/child disputes.

To allow the development of normal self-esteem, parents would treat children as full human beings (albeit smaller, less knowledgeable, and less mature than adults). From birth, each child would be allowed and encouraged to develop her own selfhood, not treated as her parent’s property or servant. Parents would be encouraged to practice democracy within their household and include the children whenever possible in making decisions that affected them.

As children matured and demonstrated they could take on more responsibility, they would be given more control over their lives until they graduated into adulthood. When young adults demonstrated that they were responsible enough to nurture, guide, support, and live cooperatively with others, they would be encouraged to bear their own children.

In a good society, there would be fewer spectator events than now and many more cultural events geared toward bringing people together and participating such as dances, rituals, songfests, and cooperative games. These social events might be facilitated by trained social directors who knew how to encourage positive interaction. Young people would have special safe, structured venues for interacting with potential mates, and they would be offered clear and supportive guidance for dealing with the strong emotions and difficult issues that surround love and sexuality. In addition, people would be encouraged to perform community service tasks that would help the young, sick, or infirm and engender compassion for and connection to others in society.

A society that supported its children well, taught them personal responsibility and democracy, and preserved their self-esteem would eventually grow into a society of capable, self-assured adults who looked out for others. These adults would be emotionally healthy and could get along with their family and neighbors. If this society also provided connection and support, far fewer people than now would be isolated or feel lonely or unloved. Problems of alcoholism, drug abuse, mental illness, sexual abuse, domestic violence, suicide, and teenage pregnancy would be far less common, perhaps even rare.

Education

He who opens a school door, closes a prison.

Like now, schools in a good society would offer information about how to do useful things (read, write, compute, and so on). Furthermore, they would offer a range of perspectives and ideas, explain the merits and pitfalls of each, and help students evaluate each perspective for themselves. Schools and other cultural institutions would encourage people to think for themselves rather than blindly accepting what they are told.

Additionally, schools would address everything children need to learn to be happy and responsible citizens including human values and rights, interpersonal relationships, emotional counseling, nonviolent conflict resolution, democratic decision-making, economics, health, leisure, music, drama, visual arts, sex, and spirituality. Students would also learn about other people and their religions and cultures to help prevent racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, and so forth.

In addition, schools would teach democratic ideals by example: the schools themselves would be organized as democratically as possible, giving substantial power to students on issues that concern them. Students would work cooperatively together and teach each other.

For much of their education, students would go out into their communities and learn by watching, querying, or working with adults. When they were mature and skilled enough, students might also research critical community concerns and publicize their findings. Not only would they learn research and evaluation skills — important skills for any citizen — but they would provide a useful service to their community.

Economics

In a good society, businesses would produce only useful goods and services, and they would produce these items in a way that is not destructive either to the people who do the work or to the environment. Businesses would prosper only when they provided useful goods or services to people, not through luck, dishonesty, corruption, intimidation, or pandering to people’s addictions. Furthermore, decisions about what is produced and how it is produced would be made democratically, and the proceeds of production would be equitably distributed to everyone.

Too many people spend money they haven’t earned, to buy things they don’t want, to impress people they don’t like.

For example, several utopian novels describe economic systems that mostly achieve these goals:

In Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel Looking Backward, everyone — whether working or not — is issued a “credit card” at the beginning of each year. Each of these cards has the same value — thus ensuring equal consumer power for every person. Each person is free to buy whatever goods and services she wants throughout the year — thus ensuring privacy and liberty. To provide these goods and services, everyone is required to work a certain amount each year until retirement at age forty-five.

In Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia, all production must adhere to strict environmental requirements. Moreover, in this people-oriented society, service workers insist that every customer treat them as peers, not as machines performing a service.

On the planet Anarres in Ursula LeGuin’s The Dispossessed, there is no money. Raised to value their fellow citizens and to take responsibility for their planet, everyone just takes what they need to live a simple life from storage warehouses and does the work that is required to stock the warehouses. Everyone does both manual and intellectual labor.

Most current economists see competitive markets as efficient ways for consumers to express their individual needs and desires, for producers to satisfy these requests cheaply, and for entrepreneurs to address unmet needs by starting new businesses. Markets enable individual parties to accomplish this all privately by directly bargaining between themselves. However, most progressive economists also support strong government regulation to protect the environment, to protect worker health and safety, and to prevent concentration of power in powerful monopolies. In addition, they support strongly progressive taxation to redistribute income and wealth more equitably. Most progressive economists also support worker- and consumer-owned cooperatives.

Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone.

Some progressives go further. For example, Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, in Looking Forward: Participatory Economics for the Twenty First Century, propose a radically cooperative and non-hierarchical economic system that emphasizes treating everyone well. In this system, information about the value and cost of goods and services would be exchanged directly between consumers and producers. Both groups would mutually make decisions about what and how much was produced. Everyone would consensually decide the appropriate level of overall production.

In this system, every adult would be a member of two committees: a committee comprising every person at a workplace and a consumer committee made up of every person in a neighborhood. Workplace committees would decide what that workplace produced or what service it provided. The committee would also decide how people produced the product or service and who did each job task. Every person in a workplace would make work decisions on an equal footing with everyone else. Moreover, each job would consist of a balanced set of tasks — some conceptual, some manual, some fun and empowering, some boring and rote — so that everyone shared the good and bad, and everyone developed confidence and skills in all areas. Job tasks would be optimized to be efficient, enjoyable, and educational (rather than optimized for profit). Products and production would also be adjusted to reduce pollution and preserve natural resources.

At the receiving end, every consumer would get roughly equal shares of the total production of society. Each person could decide individually which of the particular goods and services produced she wanted for herself. Each person would decide with her neighborhood committee which community facilities to build (like new housing or medical facilities) and — with everyone in society — which national and international facilities to build.

Through ever-larger councils of these committees, everyone in their roles as consumers would negotiate with everyone in their roles as workers to decide for the society exactly how many goods and services would be provided each year. There would be an extensive, iterative process, guided by skilled facilitators that would start with the previous year’s levels and then adjust them to reflect current desires. Proposals for particular consumption levels made by individuals, neighborhood committees, and workplaces would be summed through the councils until there was an overall societal balance between production and consumption. Then each workplace would produce or provide whatever it had agreed and consumers would receive whatever they were promised.

As a society, people could decide that everyone would work hard throughout the year and receive many goods and services or that they would all work less and have less. They could also decide to use large amounts of natural resources, or they could choose to conserve resources and minimize the impact on the environment.

As consumer desires or production techniques changed, workplaces would change the work they performed. When an item was no longer needed, the work group that produced it would switch to producing something else.

In this system, no one would be rich, and no one would be poor. Every able-bodied person would work, but no one would be exploited. Children and those who were disabled, sick, or infirm would all receive their fair share even though they might contribute less time or work. Everyone in society would have roughly equal power and wealth.

When human rights conflict with property rights, I must choose humanity.

By providing the essential basics and an equitable distribution of some luxuries to everyone in society, this system would encourage cooperation, altruism, and mutual aid and discourage greed and possessiveness. Since no one would fear economic disaster, there would be no need for personal savings or insurance. Since all children would be provided for, there would be no need for inheritances. There would also be no need for advertising to convince us to buy things we do not need.

No one would pay taxes since every service now provided by government would be provided by a work group just like any other important service. Also, there would be no large corporations threatening workers with job loss or manipulating government agencies.

Albert and Hahnel lay out a detailed plan covering the making of decisions and the provision of goods and some services. Less developed are their ideas about how services like long distance freight hauling, news reporting, housework, education, and emotional counseling would be provided. It is also unclear how decisions would be made about who did the work and how hard people worked. Albert and Hahnel do not even begin to address more difficult areas such as how society would decide who would do theoretical research, produce fine art, or provide entertainment. Clearly, these subjects need more development.

Still, a society based on their ideas would be far superior to our current system. It would eliminate poverty, encourage cooperation, and encourage full democratic participation in economic decisions.

The exact nature of the economic system in a good society must be decided consensually. It is possible that different regions would make different decisions and, accordingly, a good society would include a variety of cooperative economic systems.

The Mondragon Cooperative

The large, long-lived Mondragon cooperative in Spain provides a real-world example of an alternative system that incorporates many social goals.[34] Mondragon, started in the mid-1950s, is a network of more than 170 worker-owned cooperatives serving 100,000 people and employing 21,000. It includes a worker-controlled bank, a chain of department stores, high-tech firms, appliance manufacturers, and farms as well as housing, education, and research and development organizations.

Though certainly not ideal, Mondragon has forged innovative and mostly responsive democratic decision-making structures and encouraged participation and community. For the most part, people decide cooperatively how to allocate capital and which products to manufacture.

Resources

A good society would husband its resources carefully by re-using and recycling materials whenever possible and only mining, logging, or tilling when it was absolutely necessary. To minimize damage to the environment and to human health, a good society would only produce and apply fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides when there were no other options. Plants would be bred primarily to be healthy, tasty, and disease-tolerant and only secondarily for appearance and long shelf life.

A society that honored good citizenship more than consumption would encourage people to spend their time helping their neighbors and looking out for the common good instead of shopping for and showing off possessions. A good society would also encourage low-impact fashions and lifestyles. For example, computers could be manufactured so that it was easy to dismantle them and recycle all their components. Clothes would inflict a much smaller toll on world resources if they were made to last for many years, they were made from easy-to-grow materials like hemp, and they were dyed only with biodegradable dyes. If designed well, these simple clothes could still have flair and flatter their wearers. People would need fewer kitchen and household items if they lived in larger households (as in extended families or co-housing) or if they shared more with their neighbors. Video conferencing could replace a large percentage of business travel. Vacation travel would be less necessary if neighborhoods were desirable living places and work were not so onerous.

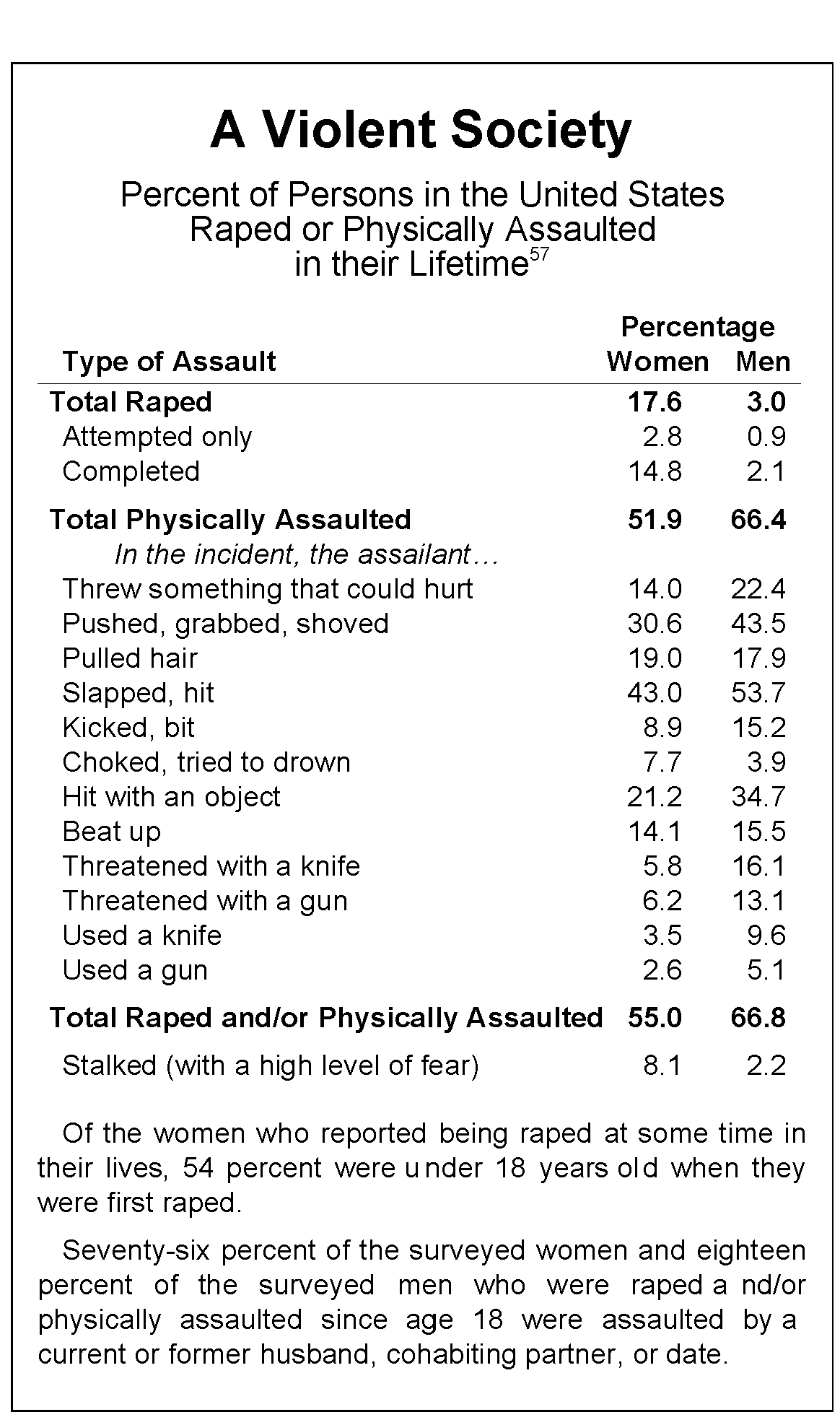

[Picture of Figure 2.1A]Figure 2.1: Good Responses to Conflict Situations

Conflict is inevitable between people unless they are all perfect or identical. However, conflict does not necessarily mean that people must fight with each other in horrible ways. In a good society, people would employ positive responses to conflict such as the ones listed here.

| Society Conflict Point | Assumed Root Cause | Typical Unhealthy Solutions | True Root Cause | Preferred Solutions in a Good Society |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Inability to produce good work Not allowed to try |

“They are stupid, lazy, or lack talent” “That’s not something girls/ young people/ new employees, etc. can do” |

Condemnation, belittlement Domination by those with more information or skills Channeling into “jobs they can do” or “appropriate jobs” |

Youthful ignorance, inexperience, lack of skills Ignorance about other cultures Emotional hurts Prejudice, oppression |

Education (formal or informal) Skill training Apprenticeship, guidance Tutoring Travel Support, nurturance Provide equal opportunity and affirmative action to those disadvantaged |

|

Honest disagreement among those trying to work together |

“Those people had an inferior upbringing” “Those people don’t know what they are talking about” “They’re crazy” |

Control by leaders or patriarchs (hierarchical authority) Majority rule backed by police Abdication by those who are more easy going Individualism, isolation, escape |

Different experiences, perspectives, cultures, or insights |

Rational debate based on facts Scientific experiments to test theories of reality or to determine the best way Cooperative decision-making (problem solving and consensus) Negotiation, mediation Amiable separation |

|

Craziness (irrationality, obstinacy, inhibitions, compulsions, prejudice, addictions, depression, violence) |

Genetic inferiority Stupidity Innate personality defects (evil) Incurable emotional hurts |

Tough it out Cultural/social control (social sanctions, condemnation, belittlement) Psychiatric hospitals and asylums Laws, police, courts, jails Threats, intimidation Monitoring, surveillance, reconnaissance |

Emotional hurts (typically from childhood) |

Support, nurturance Altruism, compassion Emotional counseling therapy Appeals to conscience Nonviolent resistance or intervention Non-destructive childrearing |

|

Privilege (injustice and domination — congenital, inherited, or developed imbalances in resources or power) |

Innate destiny (birthright, luck, or reward for hard work) “There’s not enough to go around” |

Promotion of myths that those who are wealthy or powerful deserve to be so and those who are poor or powerless are unworthy and deserve their poverty and lowly place Hierarchy of domination (everyone gets to dominate someone else except those at the very bottom who are powerless to do anything about it) Guilt-induced charity or pity Violent insurrection or revolution to overthrow powerholders |

Systemic forces in the society that propagate themselves (those with power or wealth have the means to maintain and increase their power and wealth) “Power corrupts” |

Altruism, compassion, gift-giving Redistributive laws (progressive income taxes, estate taxes, wealth taxes, etc.) Nonviolent struggle |

Figure 2.1 Good Responses to Conflict Situations (Continued)

| Society Conflict Point | Assumed Root Cause | Typical Unhealthy Solutions | True Root Cause | Preferred Solutions in a Good Society |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conflicting wants |

Innate personality defects (envy, jealousy, greed, lust for power) Inherent reality (not enough to go around) |

Moral condemnation Channeling onto work treadmill (encourage people to work hard so they can buy what others have) |

Contempt, scorn, ridicule, disdain, and slight by those who have more Advertising that induces wants and needs |

Eliminate imbalances in wealth and power New society attitude: adjust wants and needs to what the society can reasonably produce Emotional counseling therapy and healing Non-destructive childrearing |

|

Difficult work (arduous, boring, etc.) |

Nature of reality Laziness |

Poverty (to force everyone to work) Slavery The allure of upward mobility: great wealth, privilege, and power for those who work hard |

Nature of reality (but not nearly as much as we now assume) Societal contempt for routine or repetitive work |

New society attitude: value work that is important to the creation and sustenance of a good society Reevaluate work to see if it is truly needed (all essentials can be provided with much less work) Reduce hours in the work week Rotate jobs so no one has to do the same task for too long a time Allow people to have control over their work so they do not feel hemmed in Allow people to see the results of their work so they can take pride in it Provide assistance when the work gets overwhelming |

|

Especially unpleasant or dangerous work that must be done |

Nature of reality Laziness |

Poverty or slavery (to force those who are ignorant or less powerful to do unpleasant jobs) Convince people they are unworthy to do anything but “bad” jobs Excessive incentives (excessive pay or privilege) |

Nature of reality (though not nearly as much as we are led to believe) |

As much as possible, automate all unpleasant and dangerous tasks Value all jobs that are important to the maintenance of a good society Rotate unpleasant tasks so everyone shares them equitably Provide incentives commensurate with the unpleasantness of the work |

|

Isolation, lack of community and social support |

Nature of reality Character flaws |

Hiring or coercing some people to support or entertain others (including prostitution) |

Time constraints Fear of being emotionally hurt |

Reduce the work week so people have more time to interact and support each other Emotional counseling therapy Bold, loving steps towards others (initiative and compassion) |

Cities, Neighborhoods, and Transportation

Cities would be planned by city planners (with input from and ultimate control by the residents) to make them as livable as possible — rather than planned in the ways they usually are now: by real estate developers and builders who are trying to maximize their profits. Communities would be designed so that people could live near their workplaces and their friends as well as near stores, health clinics, theaters, and parks. Then most people could walk or ride a bicycle for the majority of their daily needs and desires, and they would spend much less time and far fewer resources commuting. Automobiles would only be needed to visit rural or distant places, and buses or trains could satisfy this need. Much of the half of all urban land now devoted to automobiles (for roads, parking lots, gas stations, new/used car lots, and so forth)[35] could then be used for other purposes or left as open space.

Currently, people often move to rural or suburban areas to escape from noise, pollution, and crime, or they move to rich neighborhoods with good schools and relatively low property taxes. Several changes, positive in their own right, would eliminate these reasons for abandoning cities:

- Schools would be improved so that each was as good as the best are today and all would be essentially equal in quality.

- Industrial plants would be cleaned up so that they did not emit noxious fumes and chemicals into the air and water around them. Sound-absorbing barriers or hedges would be constructed to keep industrial noise away from nearby residential areas.

- Houses would be built solidly so neighbors could live near one another without being bothered by each other’s noise.

- Street crime would be vigorously pursued so that no area became dangerous. Eliminating poverty and drastically reducing child abuse would also end the underlying impetus for most crime.

U.S. Militarism

“The American military is, at this moment, more powerful relative to its foes than any armed force in history — stronger than the Roman legions at the peak of the empire, stronger than Britannia when the sun never set on the Royal Navy, stronger than the Wehrmacht on the day it entered Paris… The United States of the year 2000 is the greatest military power in the history of the world.” — Gregg Easterbrook, “Apocryphal Now: The Myth of the Hollow Military”[36]

The United States has essentially no military enemies. Moreover, there are virtually no countries even capable of attacking U.S. territory. Still, the U.S. military controls vast resources — enabling it to dominate the world.

Military Budget

- The U.S. military had budget authority of $311 billion in FY 1999 — about 41 percent of the total federal funds budget.[37]

- The United States and its close allies spend more on the military than the rest of the world combined, accounting for 63 percent of all military spending. The United States by itself spends 36 percent of the world’s total military budget — up from 30 percent in 1985.[38]

- The U.S. military budget request for FY2001 is more than five times larger than that of Russia, the second largest spender. It is more than twenty-two times as large as the combined spending of the seven countries identified by the Pentagon as likely adversaries (Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Libya, North Korea, Sudan, and Syria). It is about three times as much as the combined spending of these seven potential enemies plus Russia and China.[39]

Military Might

- In 2000, the United States military included:

-

- 12 Navy aircraft carrier battle groups

- 10 Navy air wings

- 12 Navy amphibious ready groups

- 55 Navy attack submarines

- 12 Air Force fighter wings

- 163 Air Force bombers

- 10 Army divisions

- 2 Army armored cavalry regiments

- 3 Marine Corps divisions

- 3 Marine Corps air wings

- It also included thousands of support ships, vehicles, and aircraft as well as over 5,000 nuclear warheads on submarine- and land-based ballistic missiles and thousands of conventionally armed missiles.[40]

- “The U.S. Navy boasts more than twice as many principal combat ships as Russia and China combined, plus a dozen supercarrier battle groups, compared with zero for the rest of the world. … America today possesses more jet bombers, more advanced fighter planes and tactical aircraft, and more aerial tankers, which allow fighters and bombers to operate far from their home soil, than all the other nations of the world combined.”[41]

Military Personnel

- At the end of FY1999, there were 1.4 million active-duty U.S. military personnel, 860,000 reservists, and 700,000 civilians.[42] Over 250,000 of the active-duty personnel were stationed in foreign countries or on ships.[43]

Foreign Deployments

- “America is the world’s sole military whose primary mission is not defense. Practically the entire U.S. military is an expeditionary force, designed not to guard borders — a duty that ties down most units of other militaries, including China’s — but to ‘project power’ elsewhere in the world.”[44]

- The U.S. Army has more than 100,000 soldiers forward stationed around the world — and more than 25,000 are deployed in over 70 countries every day of the year.[45]

- U.S. Navy deployments abroad have increased by 52 percent since 1993. Army deployments have increased 300 percent since 1989. Air Force deployments have quadrupled since 1986.[46]

- The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) provides military training to more than 100 countries annually.[47]

Arms Exports

- In FY1995, the federal government spent over $477 million and dedicated nearly 6,500 full-time equivalent personnel to promote U.S. arms sales overseas.[48]

- From 1995 to 1997, the United States exported $77.8 billion in arms, about 55 percent of the global total.[49]

- From 1995 to 1997, the United States exported $32 billion in military arms to developing countries. 51 percent of these arms went to non-democratic regimes.[50]

Military Industry

- The defense industry now (1999) employs 2.2 million people, about 2 percent of the civilian workforce.[51]

Research and Development

- In 1997, the U.S. Department of Defense spent $33 billion for research and development (R&D), while the Department of Health and Human Services, a distant second, spent about $12.2 billion for R&D.[52]

Waste and Fraud

- The U.S. General Accounting Office reports that no major part of the DOD has been able to pass an independent audit. The DoD is not able to properly account for billions of dollars of property, equipment, and supplies, nor can it accurately report the costs of its operations.[53]

News Media

“The information citizens need to know to responsibly govern their society.“

Without solid information, citizens cannot make good decisions. In a good society, there must be a wide variety of information sources and the main sources must be held to high standards of journalistic integrity. Journalists always bring their own prejudices to their work and have a tendency to support the people they know or like. So there also must be checks and balances to minimize this influence. Some examples of news reporting in a good society:

- There would be many news organizations working independently of each another. At least two or three main news organizations would cover any particular region, and many smaller news organizations would focus on a particular issue or present a particular perspective.

- Funding for news reporting would come from sources other than advertising to eliminate dependence on sponsors. Individuals might pay for their news sources or the government might support them with tax dollars.

- The amount of resources allocated to each news organization (including the number of journalists, the number of TV channels, and the amount of radio spectrum) might be determined each year largely by how many people watched, listened, or read their newspapers and broadcasts. To ensure that dissenting voices were allocated ample resources to express themselves, a group who disagreed with the main news organizations might still be given resources for one year to launch a newspaper, TV show, or radio show. This would give them enough time to win over viewers, listeners, or readers.

- Journalists would be prohibited from accepting gifts or favors from anyone they covered.

- Oversight groups would challenge poor, misleading, or inaccurate coverage or socially destructive perspectives.

A Militarized World

- Since World War II, the world has spent $30–35 trillion on arms.[54]

- Global spending in 1999 on education was $80 billion. Global spending on the military was $781 billion.[55]

- In the wars of one decade, more children were killed than soldiers. Child victims of war include an estimated two million killed, four to five million disabled, twelve million left homeless, and more than one million orphaned.[56]

Foreign Policy and National Defense

In this society, it is considered immoral to walk around wearing no clothes, but perfectly acceptable to build weapons of mass destruction.

In a good society, the United States would no longer exploit the resources (oil, minerals, timber, agriculture, and labor) of other countries. This would greatly reduce the need for foreign military bases and for a bloated military budget. The cost of these foreign goods would probably go up, but this would be offset by the decrease in the vast resources now consumed by the military.

As much as possible, the people of the United States would cooperate with the people of other countries and treat them honestly, fairly, and compassionately. People would think of themselves as global citizens in fellowship with all other humans, not as U.S. nationals competing with other countries.

To provide defense against whatever enemies might still exist, everyone would be trained in nonviolent, civilian-based defense techniques and organized into nonviolent reserve militia units. If necessary, the country might maintain some minimally sufficient level of armaments and a small, trained military.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.

Government

In a good society, government would exist to nonviolently protect and support all people, instead of defending the property, wealth, or ideology of the wealthy and powerful. The government would be responsive and responsible to ordinary people. It would work to eliminate corruption, inefficiency, waste, and dishonesty.

To achieve these goals would require a different governmental structure than our current one — one that vastly reduced the temptations of wealth and power and that had even more checks on power. It would also need to be a more activist government that sought to restrict the concentration of power everywhere in society.

For example:

- The government would have more regulatory agencies with broader power to challenge society’s institutions. Moreover, these regulatory agencies would be regulated by independent oversight agencies that would be made less susceptible to their own misconduct by having only the power to expose corruption.

- When appropriate, decisions that are now made at a global, national, or state level would be decentralized to the local level, thus limiting the power of any individual person or group. Only those decisions challenging another large institution or those requiring a broad response would be made at high levels.

In your public work, don’t be afraid of exposure: If you do it, be proud of it. If you’re not proud of it, don’t do it.

- Regulations would ban all gifts and favors to any current or past government officials. Authorities with broad power would be forced to shift to other work after a time to prevent them from becoming entrenched or susceptible to corruption.

- To prevent unsavory backroom deals, all decision-making meetings would be publicized in advance and open to journalists and citizens.

- The government would also provide a democratic forum for all of us to struggle together — providing skilled facilitators who could help us decide how we wished to balance our conflicting needs and desires with those of others, with those of future generations, and with the global environment. Currently, we are usually only spectators, relegated to watching from the sidelines while wealthy interests dictate our society’s future.

Democratic Structures

Our current democratic system relies on majority votes to elect representatives who then use majority votes to pass laws. Individuals have little input into the process. To protect them from possible oppression by the majority, minority factions are granted basic rights of privacy and well-being.

The voice of the majority is no proof of justice.

This system of “majority rule, minority rights” gives too much power to majorities and does not go far enough in protecting the rights of minorities. It assumes and encourages self-interest and competition, which often leads to selfish and anti-social behavior. Under such a system, a group can garner a majority honestly by convincing others of the merit of their proposals. But under this system, a group can also secure a majority disingenuously by misrepresenting their motives or the impact of their proposals or by coercing, bribing, or manipulating supporters. With this ill-gotten majority, they may then grab control and secure benefits for themselves while taking no responsibility for the common good. They may deliberately or inadvertently exploit and oppress individuals or minorities. It is particularly easy for an unsavory majority to ignore or overrule those who cannot participate in the process such as animals, plants, the natural environment, unborn generations, infants, children, and people who are mentally retarded, disturbed, senile, weak, or homeless. Because the current system rewards greed, it can rarely find good solutions or determine a fair allocation of benefits.

A man must be both stupid and uncharitable who believes there is no virtue or truth but on his own side.

A good society demands a much better system — one that requires the consent of everyone and provides stewardship for those who cannot speak for themselves. Further, such a system must encourage everyone to work honestly and cooperatively with one another to meet everyone’s basic needs and to support everyone fairly. Such a system would seek to provide for community needs without infringing on individuals’ rights.

This type of democratic system can only occur when virtually everyone in the society wants it to work and everyone attempts to look out not only for themselves but also for other individuals and for the society as a whole. They must care about the society and feel a strong sense of responsibility for others — as people often do in a tight community. They probably must also feel a strong connection to one another — much as they feel towards members of their family. Establishing such a system requires people to feel they “own” the society and reap great benefit by being part of it. People must be strong and responsible: adhering to their own beliefs and values as well as supporting community goals.

Decision-Making System

Rather than a system of winner-take-all elections for representatives who may or may not represent a constituency or may or may not look out for the common good, a good society would have a more direct and participatory decision system. If important decisions were decentralized to the local level, people could meet in relatively small groups to discuss the issues and look for solutions that would best solve society’s problems. This might require a great deal of time, but would result in much better decisions. It would also ensure that society was responsive to the needs of people.

Liberty means responsibility. That is why most men dread it.

Most issues would not require everyone’s participation — only those interested in a particular issue would absolutely need to attend. Some people would likely devote much of their time to civic affairs while others would only participate when crucial issues arose or when they were concerned that poor decisions were being made. To ensure accountability to the whole community, any final decision might require a 95 percent or 99 percent acceptance vote by everyone affected. This would not be a vote of desire or preference but merely an acknowledgment that the decision was tolerable and that a valid body made the decision (one with a large enough quorum and that included all those concerned).

Ensuring Democratic Decision-Making

A good society allows everyone to have a say in the important matters that affect their lives. But to sustain a good society, they must also make decisions that are good for the whole community. This requires that everyone be included in the decision process, have access to all the necessary information to make good decisions, and take responsibility for making decisions that are good for the group. They must have the interest, time, and skills to listen carefully to everyone’s perspectives and concerns, evaluate the truth of each perspective, work cooperatively with others to come up with creative solutions, and finally decide on a solution that best addresses the needs of the group. Anything less will result in poor or irrational decisions or domination by one or a few people. Bad decision processes, like our current system, often simply tally the ignorance, prejudices, and biases of the dominant group or the majority.

Nothing is more odious than the majority, for it consists of a few powerful leaders, a certain number of accommodating scoundrels and submissive weaklings, and a mass of men who trot after them without thinking, or knowing their own minds.

True democracy thus probably requires using some form of consensus decision-making process, practiced skillfully and effectively by those affected. Our current society has prepared us very inadequately for such a task. A good society must devote extensive resources to teaching everyone the skills of cooperative decision-making, providing everyone with the information necessary to make good decisions, and ensuring time to make good decisions.

To encourage cooperation and high principle, there might be a short community-building ritual (like standing in a circle and holding hands with others or reading an inspiring quotation) before each session. When information was needed to inform a decision, researchers would turn to a variety of sources and investigate each thoroughly. Advocates for particular positions could add their information and make their desires known. Then the group would prepare a wide range of options and delineate the advantages and disadvantages of each one. Once the group thoroughly explored all options, most people would probably see that a few were superior and the rest could be eliminated from consideration. Most people would also recognize that none of the remaining options was perfect, but all were acceptable. Then strong preferences for a particular option or a majority vote of those at the meeting could determine the final choice. On highly controversial issues, the group might make decisions by a super majority vote (perhaps 66 percent or 75 percent), or it might defer the decision for a few months or years until a true consensus emerged.

Cooperation would be essential, but dissent would also be accepted and supported. Dissidents would be encouraged to question assumptions, criticize decisions, and closely monitor the effects of policies over time. Lobbying would be tolerated, but discouraged in favor of mutual exploration and a principled search for truth.

National or global decisions could be made by spokespeople from each local area. These spokespeople might be empowered to agree only to decisions that their local group had already endorsed. In cases of impasse, they would attempt to forge new options based on the best ideas of their local groups. Then they would take these new options back for ratification by the local groups. If ratified, they would then meet again with the other spokespeople and make a final decision. This cumbersome process might be expedited by traveling discussion facilitators, video conferencing, electronic mail, electronic bulletin board discussion groups, and other techniques.

Safety

Unlike our current society in which war and violence are often glorified, children would be raised so that they considered the idea of assaulting another person repugnant. As adults, they would then have no desire to hurt another person, and they would recoil from any kind of violence. They would also be taught how to resist aggression nonviolently.

A good society would be safe at all times of the day and night. Men and women could walk alone anywhere without fear of assault, rape, or harassment.

It costs the same to send a person to prison or to Harvard. The difference is the curriculum.

Rather than relying solely on police, everyone would be encouraged to recognize destructive behavior and to interrupt it whenever it arose. Individuals working together would use the methods of rational argument, appeals to conscience, mediation, emotional counseling, and nonviolent struggle to enforce community standards. Militaristic ideas of domination, control, hatred, punishment, and revenge would be discouraged. Weapons would be restricted. To handle the worst situations, unarmed police would be trained to intervene and to subdue people without hurting them.

Courts would primarily mediate disputes. They would provide a forum for people to explain how others’ destructive behavior hurt them and ask for restoration. For malicious crimes, specially trained counselors would support and counsel the transgressors to heal them of whatever emotional disturbance drove them to hurt others. Those who could not change would be required to live and work in a special area separate from the rest of society and be continually monitored so they could not hurt anyone. Their crimes would be condemned, but they would not be tormented, rejected, or hated.

Addictions and Drug Policy

A good society would discourage the use of mind-numbing drugs. It would also try to help anyone trapped by an addiction to drugs, alcohol, tobacco, nicotine, sugar, sports, gambling, sex, television, computers, or any other substances or practices around which people develop destructive obsessions. Anyone who wanted help to end her addiction would be assisted by trained counselors and supported by others trying to overcome the same addiction. Only those whose addictions caused antisocial behavior would be prevented from pursuing the addiction.

This is just a preliminary description of a few elements of a good society. The books and articles listed in Chapter 12 are invaluable in filling out this vision and suggesting other possible elements. Appendix A describes a variety of interim measures that could move the United States toward this vision.

Making This Vision Possible

Many of the ideas described here seem impossible in our current society and they are. In our current society, power is much too concentrated to allow many of these ideas to work. In our current society, there is so much misleading propaganda that most people are severely misinformed. Moreover, our current society breeds large numbers of angry, misanthropic, cruel, violent, and savage people with whom it is extremely difficult to cooperate or even to co-exist. It is only as our change efforts begin to transform people and society that we could produce sufficiently favorable conditions to allow these ideas to be implemented.

The rest of this book explains how we might go about this task.

Next Chapter:

3. Obstacles to Progressive Change

Notes for Chapter 2

What I call “a good society” is similar to that described by many other authors and given a variety of names. For example:

Activists in the Civil Rights movement of the early 1960s, including Martin Luther King, Jr., called it “the beloved society.”

Charles Derber, in The Wilding of America: How Greed and Violence Are Eroding Our Nation’s Character (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996, HN90 .V5D47 1996), uses the term a “civil society” and contrasts it with “wilding” (self-oriented behavior that hurts others and damages the social fabric):

Civil society is the underlying antidote to the wilding virus, involving a culture of love, morality, and trust that leads people to care for one another and for the larger community. A civil society’s institutions nurture civic responsibility by providing incentives for people to act not just in their own interest but for the common good. (p. 145)

Riane Eisler calls it the “partnership way.” Riane Eisler, The Chalice & The Blade: Our History, Our Future (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, HQ1075 .E57 1987); Riane Eisler and David Loye, The Partnership Way: New Tools for Living and Learning (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1990, HQ1075 .E58 1990). The Center for Partnership Studies, P.O. Box 51936, Pacific Grove, CA 93950, (831) 626–1004.

For another list of basic elements of a good society, see Lester W. Milbrath, Envisioning a Sustainable Society: Learning Our Way Out (Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1989, GF41 .M53 1989), pp. 79–83. He proposes that a good society (one that would sustain a viable ecosystem) would include the following four core values:

• A high quality of life

• Security

• Compassion

• Justice

These values would be supported by eleven instrumental values:

• Fulfilling work

• Goods and services

• Health

• Freedom (lack of unnecessary restraints and provision of meaningful opportunities)

• Participation in community and societal decision-making

• Sense of belonging to a community

• Powerful knowledge (broad and deep)

• Variety and stimulation (recreation, education, research)

• Peace

• Order

• Equality

These, in turn would be supported and implemented by eight societal processes:

• Sustainable economic system (produces goods and services, provides fulfilling work, maintains economic justice, utilizes resources in a sustainable manner that preserves the ecosystem)

• Health system (medicine, self-help)

• Safety system (police forces, fire protection, defense)

• Legal system (laws, courts)

• Participation system (decision-making processes, community, civic organizations)

• Recreation structure

• Research and education system

• Convenience structure (transportation, compact city design)

The thirty articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948 by the General Assembly of the United Nations, also describe the elements of a good society. This document can be found on the United Nations’ website http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html or on this site maintained by the Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute http://www.udhr.org/UDHR/default.htm.

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum, in “Human Capabilities, Female Human Beings,” Martha Nussbaum and Jonathan Glover, eds., Women, Culture, and Development: A Study of Human Capabilities (Cambridge: Clarendon Press, 1995, HQ1236 .W6377 1994), pp. 61–104, provides a more rigorous list of eleven basic human capabilities that should be fulfilled in any good society, based especially on her study of women in developing countries:

1. Being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length, not dying prematurely, or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living.

2. Being able to have good health; to be adequately nourished; to have adequate shelter; having opportunities for sexual satisfaction, and for choice in matters of reproduction; being able to move from place to place.

3. Being able to avoid unnecessary and non-beneficial pain, as so far as possible, and to have pleasurable experiences.

4. Being able to use the senses; being able to imagine, to think, and to reason — and to do these things in a way informed and cultivated by an adequate education, including, but by no means limited to, literacy and basic mathematical and scientific training. Being able to use imagination and thought in connection with experiencing and producing spiritually enriching materials and events of one’s own choice; religious, literary, musical, and so forth. I believe that the protection of this capability requires not only the provision of education, but also legal guarantees of freedom of expression with respect to both political and artistic speech, and of freedom of religious exercise.

5. Being able to have attachments to things and persons outside ourselves; to love those who love and care for us, to grieve at their absence; in general, to love to grieve, to experience longing and gratitude. Supporting this capability means supporting forms of human association that can be shown to be crucial in their development.

6. Being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection about the planning of one’s own life. This includes, today, being able to seek employment outside the home and to participate in political life.