Inciting Democracy: A Practical Proposal for Creating a Good Society

Chapter 3:

Obstacles to Progressive Change

Download this chapter in pdf format.

In This Chapter:

There are many people trying to make the world better. Why aren’t they more successful?

This chapter first addresses some popular but faulty criticisms of progressive social change efforts. Then it describes the five main obstacles that actually thwart positive change. The next few chapters then put forth a progressive change strategy that can surmount these hurdles.

Misguided Criticisms

When change does not come the way we would like, it is easy to blame others. Progressive activists often blame those who are not working for change — calling them apathetic, ignorant, complacent, or cynical. However, labeling people does not explain their behavior nor suggest positive solutions. These labels are also unfair — it is not at all unreasonable for people to spend their time earning a living, raising their children, living their lives, and having some fun. Rather than blaming those who are not actively working for change, it is more useful to determine why progressive activists are able to live their lives and work for positive change. What has inspired and enabled them to do this?

Similarly, society assigns progressive activists full responsibility for positive change and then blames them for their limitations and blunders when they fail. For example, I often hear criticisms like these:

Too Little and Too Much Effort

- Progressive activists are not dedicated enough, and they do not do enough. They should care more and work harder. They should forfeit their careers, forgo having children, minimize social entanglements, and focus all their efforts on change.

- Activists work too hard, engaging in useless frenzy and then burning out. They should take better care of themselves and work at a sustainable pace. They should also remember what is important in life. They do not spend enough time supporting their spouses, children, and friends and enjoying themselves. To be effective, they must lead a sane, balanced life and regularly stop to smell the roses.

Orientation Too Ordinary and Too Spiritual

- Activists are not spiritual enough. They should tune into the ecological wisdom of the cosmos and open themselves to the possibilities of mystery and magic.

- Activists are too idealistic and “airy-fairy” with their heads in the clouds. They should get down to brass tacks and do the hard, demanding work necessary to bring about change.

Too Much Planning and Too Much Spontaneity

If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it.

- Activists spend too much time meeting with each other to discuss how to create change and not enough time actually doing it.

- Activists do not spend enough time considering the consequences of their actions. They too often act impulsively without adequate analysis or discussion with others — then make grievous mistakes.

Too Little and Too Much Consideration of the Poor

- Activists build too few organizations of working-class people and the poor — those who can easily see how they are oppressed and will fight on their own behalf.

- Activists spend too much time focusing on the underclass. The poor are too downtrodden to work coherently for progressive change. Those who do work for change only selfishly want to get more for themselves — they will not fight for the common good. Moreover, activists only want to align themselves with the victims of society because they pity them or identify with their pain.

Too Little and Too Much Consideration of the Elite

- Activists focus too little on educating members of the elite — those who are prosperous enough that they can attend to the common good and who can use their power and resources to end oppression.

- Activists spend too much time cozying up to the elite. The elite are inherently antagonistic to any substantive progressive change. Moreover, activists only want to align themselves with the elite because they envy their wealth and privilege.

Not Enough Purity and Too Much

- Activists should not compromise their ideals by working with others who do not share their goals. Those who share ideals should go it alone, even as a member of a small sect if necessary.

- Activists should work together in large groups and coalitions to garner enough power to create big changes instead of working in small, fragmented groups.

Focus Too Narrow and Too Broad

- Activists should work on every important problem, not just their few pet issues. All issues are connected and all are important.

- Activists should all work together on one single issue instead of scattering their efforts on a thousand different projects.

Not Enough Focus on Political, Cultural, and Personal Change

- Activists should focus pragmatically on electing progressive legislators to office by working within the Democratic Party.

- Activists should create a new political party so they can promote a truly progressive platform, even if their candidates fail to win office.

- Activists should ignore politicians and act directly to educate people and to acquire power.

- Activists should forget power and focus on shifting cultural paradigms instead.

- Activists should focus inward on their own complicity with evil and work to overcome their own power-tripping, racism, sexism, and classism.

Not Enough Attention on the Future and on the Present

- Activists should strive to teach their children progressive ideals and hope that an enlightened next generation can change society.

- Activists must change the world now so their children can grow up uninjured by current problems.

Miss the Mark

Though contradictory, these are all reasonable criticisms. Each of them reflects an important truth about the nature of society, and each may be an apt criticism of a particular change effort. Activists make many mistakes and often choose foolish or counterproductive tactics. Their understanding of the world is often incomplete or wrong and the strategies they choose are often inappropriate. However, none of these criticisms really explains why progressive change efforts do not accomplish more, and none clearly points the way to fundamental change.

These criticisms and their implied solutions miss the mark. The world is complex and diverse, so efforts to change it will also be complex and diverse. In different situations, progressive activists must act in different ways. Sometimes they must work alone — other times they must work with other groups. Depending on circumstances, they must concentrate narrowly or sweep widely, focus on highest ideals or pragmatically choose to compromise, look inward or outward, focus on the present or look to the future, work long and hard or take a much-needed vacation.

But why do activists so often choose the wrong response? And why, even when they choose seemingly effective means, do they still very often lose?

Five Primary Obstacles

Rather than simply blaming ordinary people for not working for change or blaming progressive activists for their failures, it is better to probe much deeper to discover what actually holds back social change. Why are there so few people willing or able to work for positive change? Why do progressive activists err so often? Why is it so hard for them to succeed? What gets in the way?

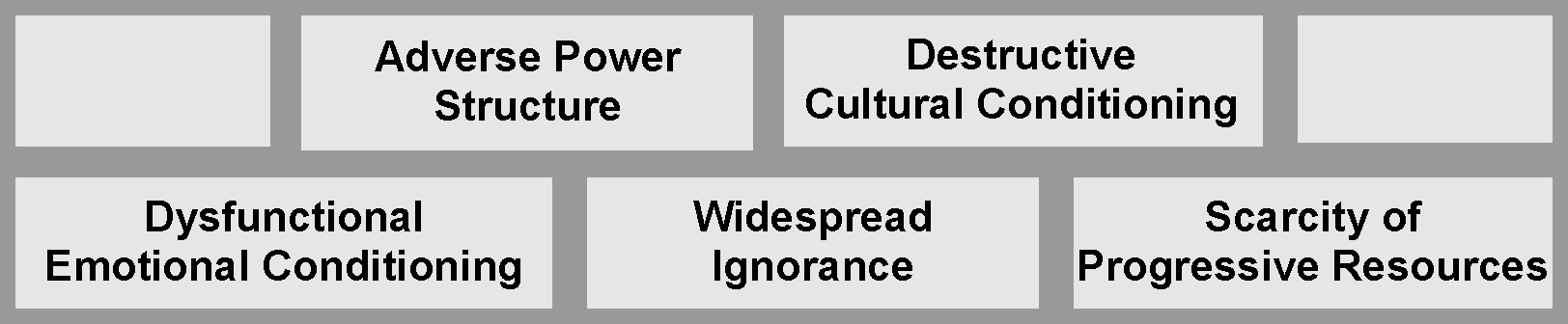

I believe five main obstacles prevent progressive activists from creating a good society:

- Adverse Power Structure: Society’s institutions and structures entice and coerce everyone into acting to perpetuate these institutions and social structures and to resist progressive change. In particular, powerful elite interests use their immense resources to thwart positive change. Regular people fear that if they stray from traditional paths they will be attacked or ruined financially.

- Destructive Cultural Conditioning: All of us grow up accepting societal norms, some of which are quite destructive. These norms powerfully dictate what is expected of us and what is permissible. Those who challenge or stray from the accepted norms in any significant way are usually criticized or ostracized.

- Dysfunctional Emotional Conditioning: All of us are hampered by internalized emotional injuries that have embedded fear and oppression deep within our psyches. This conditioning makes it difficult for us to change ourselves and often makes us resist progressive change.

- Widespread Ignorance: Most people do not know about progressive alternatives and do not have the skills to implement them. In addition, most progressive activists have few skills and little relevant experience working for change — which leads them to make many mistakes.

- Scarcity of Progressive Resources: Progressive activists have extremely limited financial resources, receive little personal support, and are too few in number.

A Wall of Opposition

Stacked together, these five obstacles comprise a huge barrier blocking positive change. Any serious effort to transform society fundamentally must overcome every one of these critical obstacles.

Obstacle 1: Adverse Power Structure

Changing society requires changing both the way people relate to each other and changing the way societal institutions are structured. The particular way that our society is structured makes it extremely difficult to bring about fundamental positive change. Our institutions and social structures entice and coerce everyone into acting in ways that perpetuate existing institutions and social structures, even those that are quite destructive.

The people who are most hurt by the current system typically have little power to make changes. They do not have the authority to order change, the money to pay for change, nor the skills to persuade others to change. Moreover, they are taught that they deserve their fate and should passively accept it.

In contrast, those who have the most authority, money, and skills have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. They are taught to believe they deserve their power and privilege and taught that they should actively fight to maintain the established order. If they feel pangs of conscience and decide to challenge the power structure or even if they just do not perform as much as is demanded by the system, they may lose their positions of power.

Most people have an intermediate level of power and awareness. They are partially hurt by the current structure, but also have a personal stake in maintaining it. They may see some of the problems caused by this structure, but they still mostly support it, often hoping that they can personally escape problems by garnering more power and money for themselves or aligning themselves with the elite.

No single person, even someone who is seemingly quite powerful, has enough power to individually bring about significant change against all the opposition generated by everyone else playing their assigned roles. Faced with broad opposition, people learn to accept the current system and to conform to its dictates, even if this means carrying out actions that oppress others.

At the Top

Our society has developed in a way that has allowed a relatively small number of people to accumulate immense power and resources. Since they reap many benefits from the present system, these wealthy, privileged members of the “upper class” have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Though progressive change would greatly improve society as a whole, it would cause these affluent individuals to lose their special privileges. So typically, members of the upper class oppose progressive change, and with their immense power, they constitute a formidable obstacle.

Sociologists C. Wright Mills and G. William Domhoff call the people who fight to maintain the privileges of the upper class the “power elite.” In a series of carefully documented books, they have systematically explored who constitute the power elite, how members of the elite exert power, and how they maintain their strength.[1]

To determine who constitute the power elite, Mills and Domhoff examined: (1) who garners most of the valued benefits of society (wealth, income, well-being); (2) who occupies important institutional leadership positions and makes societal decisions; (3) who wins when there are societal disagreements; and (4) who are considered by others to wield power. From this analysis, they conclude that the power elite encompasses primarily two sets of people: (1) leaders of the wealthy upper class who have the interest and ability to protect and enhance the privileged social position of their class; and (2) high-level employees of important businesses and organizations, particularly ones owned by the upper class. They find the power elite serves as the leadership group for the upper class and works largely on its behalf.

The Upper Class

Domhoff estimates that the upper class in the United States is a relatively small group, comprising about one-half of one percent of the total population (about one million people). Though relatively few in number, members of the upper class own 20–25% of all wealth, own about half of all corporate stock, and exercise ultimate control over a significant portion of all business.[2] They sit in a large number of the seats of power in the government and the corporate community.

Members of the upper class do not all know each other and they are not monolithic in their perspectives. However, most do share similar backgrounds, share similar lifestyles, vacation at the same resorts, and socialize in overlapping social circles. They identify with each other as the “elegant, refined, sophisticated, genteel, well-bred, upper echelon, best and the brightest.” Given their shared position in society, they also generally share an interest in maintaining their power and privilege.

Some people join or leave the upper class as their wealth and status grows or shrinks. Nevertheless, membership generally changes slowly, usually bequeathed from elite elders to their elite heirs. To ensure continuity over time, private boarding schools, elite colleges, and upper crust social clubs mold upper class children and up-and-coming new members of the elite into a cohesive group.

The Power Elite and the Power Structure

The power elite is that select group with the desire and the ability to shape public policy — often with the goals of maintaining the power and wealth of the upper class and of resisting efforts to democratize society. The power elite does not include every upper class person nor is it limited to the upper class. Still, many members of the power elite are upper class and most of the rest are aligned with upper class interests.

The power elite is not a secret cabal conspiring to oppress other people. However, members of the power elite are powerful and influential. Most do share common interests. Many of them do meet together in a variety of forums (policy conferences, business meetings, trade conferences, social clubs, and friendship networks). Many do discuss and work out mutually satisfactory policy initiatives. Many do use their power to advance these initiatives.[3] Together, their efforts to “maximize profits for shareholders,” “merge assets into more efficient units,” “reduce labor costs,” “increase productivity,” “support and defend free enterprise,” “overturn trade barriers,” “defend property rights,” “protect individual initiative,” “stamp out immorality,” “uphold law and order,” “honor traditional family values,” “maintain a strong defense,” “reform government,” and implement other seemingly innocuous and benevolent principles actually result in the oppression of billions of people here and abroad.

The owners and top-level managers in large income-producing properties are far and away the dominant power figures in the United States. Their corporations, banks, and agribusinesses come together as a corporate community that dominates the federal government in Washington. Their real estate, construction, and land development companies form growth coalitions that dominate most local governments. Granted, there is competition within both the corporate community and the local growth coalitions for profits and investment opportunities, and there are sometimes tensions between national corporations and local growth coalitions, but both are cohesive on policy issues affecting their general welfare, and in the face of demands by organized workers, liberals, environmentalists, and neighborhoods.

Many members of the power elite do not feel that they are particularly powerful. Rightfully, they see tens of thousands of other powerful people and perceive that their own ability to exert control is small. Still, compared to the average person who has few resources and does not occupy a seat of authority, members of the power elite are tremendously more powerful.

Members of the power elite are not “evil” individuals. Many deeply believe authoritarian ideology and free market rhetoric and so honestly believe their actions are benign. They typically believe they are saving the world from some greater evil like “Satanism,” “Communism,” “terrorism,” or “tribalism,” or defending against domination by “politically-correct Feminazis” or “misguided Luddites.”

The trouble with being in the rat race is that even if you win, you’re still a rat.

Some members, naïve about the true nature of social processes, go along with the system and trust that their actions are benign. Other members of the power elite, ambitiously seeking monetary gain or status, feel compelled to play according to the rules of the game even though this sometimes means they must act in ways they know are destructive and immoral. Still others try to act for the social good, but discover that the economic, political, and social structures of society force them to act in destructive ways. They find that the forces they confront are so powerful that they are not allowed to choose positive solutions. If they attempt to oppose or bypass the power structure, they are barred from acting or stripped of their power — either way, they cease being members of the power elite.

No matter what their motives, desires, or ideological bent, members of the power elite control immense resources and they use these resources to advance particular policy initiatives. These initiatives generally enable, support, and defend themselves, other members of the power elite, the upper class, and the whole power structure that permits them to continue wielding their power.

Although members of the power elite shape the power structure and generally support it, they are also manipulated and oppressed by it. They are bombarded with their own rhetoric, terrorized by their own scare stories, forced to act in proscribed ways, barred from reaching out to most other people, and prohibited from considering positive solutions to social problems. Many members of the elite feel they are trapped in a terrifying world: they feel inferior to anyone with more power, money, or status; they feel besieged by liberals, people of color, the poor, and perhaps by other members of the power elite; and their lives feel empty and meaningless.

Are You a Member of the Power Elite?

- Were you born into a prominent family? When you were a child, did most people in your community see your parents as distinguished, sophisticated, glamorous, or eminent? Are you viewed that way now?

- Did you attend a prestigious private prep school or elite college? Did/do/will you send your children to such a school?

- When you came of age, did you receive gifts or an inheritance worth more than $50,000 (beyond college tuition)?

- Are you listed in the Social Register? Do you belong to the Bohemian Club or a local upper-crust social club? Do you vacation at posh resorts?

- Does your immediate family have an annual income of more than $200,000?

- Does your immediate family have a net worth of more than $1,000,000?

- Are you a top executive or a member of the board of directors of a large corporation, bank, law firm, foundation, university, policy-formation institute, large cultural organization, or religious denomination?

- Are you an elected or appointed official at the state or national level, a top political party official, or a top military officer?

- Do you serve on any official commissions or task forces at the local, state, or national level?

- Do your direct and indirect contributions to political campaigns, political parties, or lobbyists at the local, state, and national level total more than $5,000 annually?

- Are you a member of the board of directors or do you directly or indirectly (through a foundation) contribute more than $5,000 annually to a national policy-formation institute?

If you answer yes to three or more of these questions, then you are probably a member of the power elite.[5]

The Might of the Power Elite

Backed by the enormous wealth of the upper class, members of the power elite own or exert dominant control over most of the important resources of society. Together, they have enormous holdings in land, mineral rights, factories, buildings, equipment, TV and radio licenses, patents, and copyrights. They control government commissions and regulatory agencies. They command military services, “intelligence” agencies, and police forces. They direct the news media, policy think tanks, universities, churches, banks, agribusiness, and most other industries, including the important information industries of publishing and entertainment. With these immense resources, they have the ability to obscure the truth and threaten anyone who attempts significant change.

For example, in the area of public governance, the elite can mostly control who is nominated for office, who is elected, and who is appointed to commissions and judgeships. Moreover, they can mostly determine who lobbies legislators, how issues are portrayed, which policy questions are asked, what research information is revealed, and which solutions are considered.

The public be damned!

Consider the ways that the elite controls who is elected to public office. In the current political system in the United States, candidates for public office can usually win election only if they raise hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. Candidates with large amounts of money can poll voters to discover what they want to hear, then craft dazzling television advertisements filled with alluring messages, and blast them at every voter in the district. They can completely overpower honest political discussion with verbiage and spectacle. They can also blast their opponents with vicious accusations and nasty innuendo.

Candidates who cannot raise large amounts of money have no way to tell voters about themselves or their positions on policy issues and no way to counter the misinformation broadcast by opponents. Even so-called “grassroots campaigns” (with many volunteers making telephone calls and delivering literature door-to-door) typically require large amounts of money to pay for telephones, printing, and travel. Given this environment, the candidate who spends the most money usually wins.

We have the best government money can buy.

Realistically, candidates can only raise large sums two ways. They can tap their own reserves if they are multi-millionaires like Ross Perot or Steve Forbes. Alternatively, they can solicit big donors — who are usually members of the upper class. Consequently, most candidates able to win office are members of the power elite, ideologically sympathetic to elite interests, or beholden to the elite. Tellingly, the Senate is known as “the millionaire’s club” for its large number of extremely wealthy members.

Once elected, these officeholders usually want to (or feel they must) propose legislation that supports and protects their elite sponsors. Hence, tax reductions for the rich are usually on the congressional agenda, but reductions for those below the poverty line rarely are.[6] To bolster their policy positions, politicians aligned with the elite can easily rely on reports generated by universities and think tanks — that are also backed by elite interests. In stark contrast, those who oppose elite domination usually have only the research of small, poorly funded public-interest groups.

Politicians who vote against elite interests are targeted by moneyed congressional scrutiny groups. These groups can distort the purpose of their legislation and rally people to flood them with calls and letters of opposition.

We have a governing system of the power elite, by the power elite, and largely for the power elite. Excluded from the decision arena, most ordinary people are relegated to watching silently from the sidelines as elite interests dictate the contours of their lives.

To ensure that Congress passes no law detrimental to their interests, large business and professional interests also hire thousands of lobbyists to visit officeholders in Washington and state capitals regularly. Besides barraging officeholders with their political arguments, lobbyists often confer lavish gifts and campaign contributions in a manner tantamount to bribery.[7]

The power elite also largely controls the news media.[8] The “major” news media, owned by large conglomerates, usually report on issues with enough dazzle to attract viewers and readers, but also in a way that does not offend their corporate owners. Top reporters for these news outlets usually have an upper middle-class background and aspire to wealth and prominence. This tilts their sympathies toward upper class and business interests. Those few reporters who challenge the elite are sometimes directly reprimanded by their editors or publishers, but more often, their editors simply do not assign them to important stories until they change their ways. They soon learn to censor themselves.[9]

Consequently, it is generally difficult to hear other than elite perspectives about anything but the most trivial topics. Most news articles approach issues from an elite perspective — pointing out how various options would affect “us” (the elite) and what the most prudent course of action is for “us” (the elite).[10]

When politicians and pundits say the American people want free trade, capital gains tax reductions, and less government regulation, it makes no sense. Most people couldn’t care less about these things. But if you substitute the phrase “the power elite” for “the American people,” the meaning becomes clear.

For example, the news media extensively cover issues concerning capital, trade, and military might. These issues are portrayed as important since they concern “our” (elite) interests. Other issues, even if they affect millions of people — like the health and welfare of children, unemployment, toxic wastes, or family violence — receive little or no coverage. Proposed solutions seldom include any that seriously challenge the power or wealth of the elite. As a result, virtually the only “controversial issues” covered by the media are those involving a struggle between different factions of the power elite.

When reporters do point out injustice, wrongdoing, or corruption by members of the elite, they typically frame it as an unusual aberration caused by a few greedy people. Alternatively, they may frame it as a larger problem, but one that occurred in the distant past and that responsible authorities have now fixed. They seldom place these problems where they belong in the larger context of ongoing, systemic corruption, chicanery, connivance, and domination by the elite.

On the local level, communities are usually dominated by bankers, real estate developers, and the owners and top managers of large local industries, law firms, and newspaper and TV stations. Members of the local power elite usually support the national elite, and members of the national elite support the local elite — or at least they passively tolerate each other.[11]

Elite Interests Usually Win

Domhoff finds that with their immense wealth and authority, elite interests can usually exert enough power to win struggles on important societal issues — especially those concerning economic matters like tax law, consumer protection, workplace safety, and environmental standards.

As one clear example, Domhoff details how elite interests watered down a full employment bill — one that working people greatly desired — until it had virtually no substance.[12] The Employment Act of 1946 began its life as the Full Employment Act and would have made “the federal government underwrite the national investment needed each year to ensure full employment. It would be the task of government to determine what amount was needed each year, then to make available to private industry and state and local governments the loans necessary to bring total private and public investment up to the target figure. If the loans were not utilized, the Congress would authorize money for public works and other federal projects.” (109)

This bill, which might have ended unemployment and poverty,[13] was fought by the Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, the American Farm Bureau Federation, and others. The moderate-conservative “Committee for Economic Development” then put forward a substitute bill that “fit their conception of the limited role government should have.” By the time the bill passed Congress, it “merely called for a yearly economic report to provide suggestions for dealing with threats of inflation or depression that might be on the horizon… [It] also called for a three-person Council of Economic Advisors to help the President prepare this report.” (113)

No one can earn a million dollars honestly.

Behind every great fortune there is a crime.

Two recent cases are also telling. Elite financial interests engineered deregulation of the savings and loan industry in the early 1980s, which led to wild financial speculation. When the industry collapsed in the late 1980s, federal regulators gently slapped the wrists of those who had committed fraud. Meanwhile, the federal government bailed out the industry with hundreds of billions of dollars. The news media mostly ignored this gigantic government handout to wealthy investors and instead focused its attention elsewhere — on poor welfare cheats stealing a few thousand dollars. The federal government might have taxed the rich to pay for the bailout. Alternatively, it might have taken partial ownership of savings and loan institutions or garnered some portion of S&L’s future profits in exchange for bailing them out. But these options were never considered, even though these alternatives would probably have been better for the country as a whole.

The elite agenda also governed the 1994 debate on health care reform. At the beginning of the debate, about 70% of Americans expressed strong interest in a universal, Canadian-style system of health care. In such a “single-payer” system, a government agency would serve as the single payer for all care in place of the many insurance companies that perform that role now. By avoiding the bureaucracy needed to determine who gets health care (since everyone would), a single-payer system would provide a great deal more health care at less cost to everyone. Moreover, in this kind of system, doctors would maintain their independence and would continue to decide what is appropriate care — not insurance company bureaucrats.

Progressives own or control few banks, corporations, stores, universities, think tanks, television stations, or churches. Members of the power elite own or control thousands of these institutions.

Though fair, efficient, and popular, the single-payer option was virtually ignored by the news media and Congress. The main options offered by the Democrats and Republicans involved expanding insurance company coverage, not replacing it. The debate — as portrayed in advertising and the news media — concerned only how much insurance coverage should expand and who should pay for it. Since the power elite did not favor it, the single-payer alternative was dismissed as “politically unrealistic.” As usually happens in a battle between a large industry and the public, Congress sided with the industry.

Perhaps the clearest example of elite power is the U.S. tax structure. In America: Who Really Pays the Taxes?, journalists Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele document how the wealthy are able to keep their tax rates low at the expense of the poor and middle class.[14] Barlett and Steele demonstrate the inequity of the tax code by comparing the taxes paid by two representative families in the early 1990s: Jacques Cotton, a single father of two small children living in Portland, Oregon, who earned a little less than the median family income, and then President George Bush and his wife Barbara. In 1991, the Bushes paid 18.1 percent of their $1,324,500 income for federal, state, and local income taxes, Social Security tax, personal property tax, and real estate tax. In 1992, Cotton paid 19.8 percent of his income of $33,500 for the same taxes. The tax rate on Cotton’s moderate income was nine percent higher than the rate on the Bushes’ enormous income. (17–20)

This case is not unique. The tax code allows wealthy people to write off much of their income so they only pay taxes on a small portion of the total — greatly reducing their effective rate of taxation. In 1989, more than five thousand households with income over $200,000 paid federal income tax at an effective rate of less than five percent. In contrast, over seven million households with income between $25,000 and $30,000 paid federal income taxes at an effective rate of ten percent. (46)

Barlett and Steele document how politicians change the tax code to protect the wealthy and shift the tax burden onto the middle class and poor. Summarizing, they write:

Just what kind of a [tax] system is this?

Very simply, a system that is rigged by members of Congress and the executive branch. A system that caters to the demands of special-interest groups at the expense of all Americans. A system that responds to the appeals of the powerful and influential and ignores the needs of the powerless. A system that thrives on cutting deals and rewarding the privileged. A system that permits those in office to take care of themselves and their friends. (21)

Not only have the wealthy been able to keep their taxes low, but they have also managed to mollify people by propagating several myths. Defenders of the elite contend the tax system currently soaks the wealthy and at a rate greater than ever before. They further argue that burdensome taxes discourage new investment and hinder job creation. They also maintain that American corporations cannot compete overseas because onerous taxes hobble them. (15)

Actually, taxes on the wealthy have dropped dramatically over the last five decades. An IRS study shows that the effective tax rate on the richest one percent has dropped from about 45% in 1950 to about 23% in 1990.[15] Corporations now pay much lower taxes than they did in the 1950s and at a much lower rate than corporations in other industrialized countries do.

Defenders of the elite have also routinely distorted the terms of the debate to obscure their true goals. In looking at the history of federal income taxes, Barlett and Steele conclude:

Over time, much of the debate concerning tax rates would boil down to two phrases. Tax legislation that would increase the rate on the wealthy was called “class warfare.” Tax legislation that would reduce the rate on the wealthy was called “tax reform.” (65)

Figure 3.1: Approximate Distribution of Wealth

in the United States, 1989

Source: New York Times quoting U.S. Federal Reserve data[16]

Figure 3.1 shows how skewed is the distribution of wealth in the United States. A study by the Federal Reserve shows that in 1989 the wealthiest one percent of households — those with net worth of at least $2.3 million — owned nearly forty percent of the nation’s wealth. The next wealthiest nineteen percent — with net worth of $180,000 to $2.3 million per household — owned another forty percent. This left only twenty percent of the nation’s wealth for the other eighty percent of U.S. households. The United States has become the most economically stratified of industrialized nations, surpassing even countries like the United Kingdom which have moved away from their feudal pasts.

Gross Inequity is Indefensible

There is no reasonable justification for one person to make as much money in a few days as another earns in a lifetime. No matter how smart, beautiful, refined, charismatic, brave, clever, educated, experienced, or hard working, no human being deserves to receive five thousand times as much money as another. But billionaires in our society today typically realize more return on their investments in just two days than someone paid the minimum wage earns in fifty years of hard work.[17]

Our economic system rewards luck, inheritance, chicanery, and raw power. It scarcely rewards effort and usually discounts virtue. In defending this absurd system, apologists can ultimately cite only its supremacy and invincibility: it exists, and so far, no one has been able to change it, therefore it must be worthy. Skewed political and social relations rest on similarly specious logic and equally lame excuses. They too are indefensible in a civilized society.

Elite Interests Dictate Foreign Policy

When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint.

When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.

In the realm of foreign affairs, Noam Chomsky and other critics have extensively documented how the U.S. elite supports the elite in other “friendly” countries. Atrocities committed by countries aligned with U.S.’s elite interests are usually ignored or downplayed, but those of “terrorist” countries are vociferously condemned. Indigenous peoples’ struggles against exploitation by multinational corporations or local elites are usually labeled “communist aggression” or “terrorist rebellion” by U.S. elites and are subject to U.S. military intervention or covert action by the CIA.[18] But those countries that allow western corporations to operate without restriction (“free trade”) are granted Most Favored Trade status.

For example, the United States has vigorously condemned every possible violation of human rights in Cuba and maintained a devastating blockade of this small nation for forty years. In contrast, despite the massive brutality shown in the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, the United States has downplayed much worse transgressions in China. Similarly, the United States launched the Persian Gulf war against Iraq when it invaded the autocratic government of Kuwait. However, when Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975 and killed over one-third of the civilian population, the United States did nothing to stop the violence and, in fact, continued to sell weapons to Indonesia.

I spent thirty-three years and four months in active military service as a member of this country’s most agile military force, the Marine Corps. I served in all commissioned ranks from Second Lieutenant to Major-General. And during that period, I spent most of my time being a high class muscle-man for Big Business, for Wall Street, and for the Bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism.

I suspected I was just part of a racket at the time. Now I am sure of it. Like all the members of the military profession, I never had a thought of my own until I left the service. My mental faculties remained in suspended animation while I obeyed the orders of higher-ups. This is typical with everyone in the military service.

I helped make Mexico, especially Tampico, safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefits of Wall Street. The record of racketeering is long. I helped purify Nicaragua for the international banking house of Brown Brothers in 1909–1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for American sugar interests in 1916. In China, I helped to see to it that Standard Oil went its way unmolested.

Elite Power is Hidden

The extent of elite power is concealed from most people — hidden behind a pluralist facade. In a true pluralist system, individuals band together according to their interests and struggle on behalf of their group. In an ideal pluralist system, each group wins sometimes and loses sometimes. If all groups are equally powerful, then each receives approximately an equal share of resources. Even if some are more powerful than others, over time, the theory goes, victory shifts from one to another and everyone is eventually rewarded.

However, in our actual society, the overwhelming power of elite interests ensures that they completely win most of the battles and they strongly shape the outcome in the rest. The lower echelons — the homeless and the working poor — are virtually shut out.

You can fool all the people all the time if the advertising budget is big enough.

Our society only resembles the pluralist ideal in those few cases when a conflict is between comparably powerful factions of the power elite. Regular people may also be able to win a battle if they are able to organize themselves into large enough groups to wield a significant amount of power.

Unfortunately, even in these two circumstances, the spoils are usually divided solely among the winners, rather than allocated in a way that might be best for the common good. Weak or invisible entities like young children, future generations, and the environment have no way to compete and may completely lose out.

Progressive Change is Subverted

Those progressive groups that play the pluralist game and work entirely within the existing political system are often manipulated by the elite and compromised. Since these groups have limited resources, they must enlist the help of more powerful, but less progressive players such as the news media, business people, congressional moderates, mainstream foundations, and moderate voters. However, in order to maintain their support from and influence with these groups, they usually must also adjust their political stance to fit within the norms of the established order. This often requires them to abandon their positions and limit their demands.

A politician thinks of the next election; a statesman thinks of the next generation.

Especially in Washington, D.C., progressive organizations often must bargain, haggle, and compromise to achieve even small gains. Fair-minded activists must compete with well-funded political hacks and lobbyists. Fair and sensible solutions must compete with the vested interests of businesses, trade groups, parochial labor unions, and dogmatic religious groups and with the fetishes and whims of powerful fat cats. Elite interests deliberately malign and distort reasonable solutions until these solutions seem foolish or dangerous. Those who refuse to play these power games are ignored by the influential powerbrokers and media barons or are dismissed as extremists.

As difficult as it is to play the pluralist game, it is even more difficult to bring about any truly fundamental change since this usually requires working outside the political system and challenging the core of elite power. When directly challenged, elite interests employ the full range of their formidable arsenal to resist and retaliate. Dissident groups are pointedly ignored until they grow quite large in size and stature. Then they are often slandered, harassed, belittled, infiltrated, burglarized, defrauded, and entrapped. When progressive activists are able to create some significant change, they are often threatened, jailed, fired from their jobs, assaulted, or even killed.

Help the police. Beat yourself up!

As a pointed example, in 1990 in Oakland, California, a car bomb seriously injured Judi Bari and Darryl Cherney. These two EarthFirst! organizers had been particularly effective in bringing together environmentalists and loggers to oppose clearcutting of ancient forests, the export of mill jobs overseas, and other destructive logging company practices. In investigating the case, the Oakland police and the FBI brushed aside the many death threats directed at these activists in the previous year. Instead, the authorities accused Bari and Cherney of planting the bomb, even though the physical evidence showed this was absurd.[20]

To further distract, weaken, or disrupt effective change groups, elite interests sometimes actively encourage racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia. For example, company owners often attempt to disrupt labor unions by encouraging hatred towards new immigrants, women, or less-skilled laborers. Currently, many mainstream commercial radio stations (owned and controlled by the elite) carry incendiary “hate radio” talk shows in which hosts and callers hurl racial and sexual epithets and discuss ways to kill their enemies. Federal regulatory agencies ignore the antisocial behavior of these stations but closely scrutinize progressive, nonprofit stations, which right-wing critics accuse of airing “one-sided political diatribes” and “filth.”

Vulnerability and Fear Induce Conservatism

Given the enormous power of elite interests and their ability to crush opponents, most people are quite aware of their vulnerability. The power structure does not tolerate much dissent or divergence, and people fear being singled out as rebels. People accurately perceive that the personal risk of stepping out of line and challenging the structure is usually quite large compared to the benefits they will personally gain. The risk looks worthwhile only if there is a high probability that their efforts will somehow bring about dramatic positive change.

No other offense has ever been visited with such severe penalties as seeking to help the oppressed.

This fear may also feed on early conditioning. In our childhoods, probably most of us tried at least once to stand up to the oppression we saw around us. Rather than being praised and supported for our efforts, our parents or peers may have criticized, ridiculed, ignored, ostracized, or even physically brutalized us. Small and powerless in the situation, we learned not to challenge the status quo. Even now that we are adults and even in situations where we are unlikely to be punished, our painful memories and internalized fears may hold us back.

Not only is it difficult to rebel in this society, but even those who play strictly by the rules are vulnerable. Bad things happen to good people, and our unforgiving society provides only a minimal safety net. Multitudes of omnipresent homeless people continually remind us how much worse our lives could become if we are not careful.

Many people rightfully fear that change of any sort will just make their lives worse. Power struggles are disruptive, and those people with the fewest resources usually suffer the most. For them, though the current situation may be miserable, it is at least a known and limited misery.

Moreover, our current society is not the worst possible. Though elite powers are tyrannical and oppress billions of people here and around the world, they do maintain U.S. society at a certain functional level, enabling many people to have a tolerable life. Our rich society — with its free public schools, rule of law, balance of powers, and free enterprise — does a minimal job of providing for basic needs and restraining hatred, greed, and craziness. It does mitigate — at least to some extent — bigotry and other social oppressions. It does curb the most egregious corruption and domination. People still have some freedom of religion, freedom of expression, the right to vote, and the right to form and join independent organizations. They can still exert influence on some issues.

Under capitalism, it’s dog eat dog. Under Communism, it’s just the opposite.

In comparison, alternative institutions proposed by progressive activists often seem paltry or pathetic, and activists do not usually have the resources to implement these alternatives. Those few times when activists can implement them, elite interests malign, undermine, or destroy them. Consequently, there are few viable alternatives. Many people then conclude that conventional institutions are the best ones possible.

For these reasons, many people argue philosophically, as did Dr. Pangloss in Voltaire’s Candide, that “all is for the best” in this “best of all possible worlds.” Even many poor and oppressed people, believing they will never do any better, adamantly support the status quo and oppose efforts to change it.

Obstacle 2: Destructive Cultural Conditioning

Humans are creatures of habit. Typically, we do the same things every day in about the same manner. If we did not, we would have to make decisions constantly about every facet of our lives: what to eat, when to sleep, where to go, what to do, what clothes to wear, who to talk to, what phrases to speak, what mannerisms to use, and on and on. It is much easier to find a reasonable way to act just once and then do it the same way after that.

Consequently, we adopt habitual ways of behaving, and we raise our children to act these same ways too. We socialize and civilize each other by discouraging destructive or unpleasant behavior and encouraging decorous behavior. This process establishes broad cultural norms that specify what is acceptable and expected.

All humans set up and adhere to cultural norms; it is generally a desirable way to run society. However, when cultural norms are destructive or limiting, they can block our potential as human beings.[21] For example, cultural norms dictate that young men accept their “duty” to go off to war stoically, even though they may be maimed or killed for no legitimate purpose. If young men did not accept this norm, they might refuse to fight and instead demand the end of the war system. They could save their own lives and make the world safer for everyone.

Sometime they’ll give a war and nobody will come.

Cultural norms include traditions, customs, religious practices, rituals, fashions, fads, peer pressure, and gossip. Some norms are codified into laws and regulations, but most are simply accepted as “normal behavior.” Norms may be based on deeply held moral values or they may actually violate them. For instance, many commonly accepted sales tactics violate the ethic of honesty. Advertisements also frequently depend on (and promote) the “seven deadly sins” — especially avarice, lust, and envy.[22] Most cultural norms are relevant to our current society, but some are remnants of some ancient purpose, now long forgotten yet still passed along from generation to generation.

Cultural norms are widespread and deeply instilled. Some, like fashions, are easily recognized, but most cultural norms are so pervasive that we discount their potent influence on our lives. Frequently, what we consider personal decisions are actually dictated by strong societal norms. For instance, the dominant culture urges us to marry, bear two children, eat junk food, drink coffee and soft drinks, watch television, drive cars, shop in malls, buy presents for everyone we know for an ever-increasing number of holidays, compete with others, and scoff at the government. Women are expected to shave their legs and armpits, and wear makeup and jewelry. Men are expected to follow sports avidly, drink alcohol, and act tough around other men. Most people accept without question these and thousands of other norms, large and small. It is usually only when someone refrains from owning a car, fails to buy presents for others, or commits some other heinous cultural crime that people notice.

People in groups tend to agree on courses of action which, as individuals, they know are stupid.

Norms surround us in an extensive and mostly unseen web that profoundly affects who we are, how we act, what we believe, how we vote, what we consider pleasurable, and how we think. Cultural norms influence every aspect of our lives from superficial aspects like our music preferences and shopping patterns to important societal functions like our childrearing practices.

Cultural norms even dictate the various ways that people rebel against the dominant culture. American individualism is a cultural norm. The counterculture of the 1960s required long hair, blue jeans, work shirts, and peasant dresses. Punks today must have tattoos and body piercings. Hip artists must wear black clothes and dour expressions.

Much of our core culture and norms derive from our ethnic heritage. Because everyone in our immediate family shares the same culture and norms, they are usually invisible to us. It is only in a multicultural environment that our cultural upbringing comes into view. For example, my German and English ancestry directs me to be logical, responsible, and hard working, but also perfectionistic, emotionally impassive, and uptight around physical closeness. Living and associating with people from other backgrounds and cultures for the past thirty years — especially progressive and new age activists — has led me to notice and change some of my ways. I am now much more comfortable with mistakes, emotions, and closeness. I have also learned that when other people are not logical, responsible, or hard working in the way that I am, it is usually not because they are irrational, irresponsible, or lazy (as I was led to believe), but because they are operating from different cultural norms.

Children are natural mimics who act like their parents despite every effort to teach them good manners.

Chauvinism, prejudice, bigotry, homophobia, and other oppressive attitudes typically emanate from cultural norms. Because they are implanted at an early age and held so widely, they are difficult to identify or change.

For instance, classism completely infuses our culture and deeply affects how everyone thinks and acts about money and worth. Often owning-class people are arrogant and disdainful of others. They typically do not discuss money openly. Middle-class professionals frequently are uptight, insecure, squeamish, and overly polite. They usually are embarrassed to talk about money issues. Working-class people frequently are insecure, reticent, and distrustful, yet completely open about discussing money issues.

Because classism is so common and its effects so convoluted, most people do not recognize it as the source of these myriad behaviors and attitudes. Instead they accept this conduct as normal or attribute it to quirks of individual personality. This leaves classism difficult to recognize or challenge.

The most important factor for the development of the individual is the structure and the values of the society into which he was born.

Most cultural norms are mindlessly passed along from one generation to the next. Norms that do not work eventually fade away, and new norms arise to deal with changes caused by weather, migration, or new technology.

However, some cultural norms are deliberately promoted. Cultural leaders such as newspaper columnist Ann Landers, talk show hosts Rush Limbaugh and Paul Harvey, and prominent religious leaders like the Pope, Billy Graham, and Louis Farrakhan promote particular standards of acceptable behavior. Entertainers, employers, teachers, and gang leaders also establish cultural norms in their areas of influence — some positive, some destructive. Generally, the more exposure we have to these cultural leaders, the more prestige they hold with us. Also, the more they can exert power over us, the more they influence our attitudes.

Give me a child for the first seven years, and you may do what you like with him afterwards.

With their control of society’s resources, elite interests can encourage cultural norms that bolster their power and wealth. Through corporate advertising and the entertainment industry, they have the ability to steer the dominant culture in particular directions. They promote some positive norms like litter reduction, but some elite interests also promote cigarettes, alcohol, sex, violence, militarism, mindless consumerism, deference to authority, apathy towards politics and progressive change, and hatred towards racial minorities, foreigners, immigrants, homosexuals, the poor, and anyone who challenges the status quo in other than “acceptable” ways. They relentlessly promote the idea that “capitalism is good, socialism is bad” to the extent that most people fervently believe this mantra even though they have no idea what the terms “capitalism” and “socialism” mean.

A Few Examples of Destructive Cultural Norms

- Individualism, selfishness

- Materialism and consumerism

- Competition

- Drug consumption (alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, etc.)

- Classism, sexism, racism, ageism, homophobia, etc.

- Militarism

Corporate advertising is especially effective in establishing cultural norms since it is slick, pervasive, and incessant. Every day, the average American is bombarded by three thousand marketing messages. No one can completely resist this torrent of ideas and images. Children are especially susceptible to advertising’s influence since they have less experience and understanding of the world. Typical American children now see more than 100,000 TV commercials between birth and high school graduation.[23]

There is no absurdity so palpable but that it may be firmly planted in the human head if only you begin to inculcate it before the age of five, by constantly repeating it with an air of great solemnity.

Besides promoting particular products, advertising insidiously sells the idea that any need or dissatisfaction can and should be rectified by buying something. Under the onslaught of consumer advertising over the last hundred years, selfish individualism has displaced traditional norms of community cooperation and support.

Because social norms are so strong, those who challenge or stray from the accepted order in any significant way are usually criticized or ostracized, even if their new ways are more reasonable and humane. There is strong pressure to conform and to pressure others to conform. This makes it difficult to create and diffuse new, positive cultural norms.

Obstacle 3: Dysfunctional

Emotional Conditioning

As described briefly in Chapter 1, research over the last few decades has shown that when a person is severely or repeatedly traumatized, especially as a small child, the trauma is etched into her psyche. She is then much more likely to “act out” destructive or dysfunctional behavior for the rest of her life.

Severe trauma can induce rigid, patterned behavior — behavior that may have been protective at the time of the trauma but is not a rational response to current circumstances. For example, many victims of childhood sexual abuse, whose trust was severely betrayed, find it difficult to trust other people — even their supportive, loving friends.[24]

Many people truly believe they are stupid, ugly, or worthless because they were told this repeatedly throughout their childhood.

Childhood trauma also frequently induces low self-esteem or self-hatred. Victims assume they must somehow be evil enough to warrant the physical, sexual, or verbal abuse that was directed at them. This causes them to feel fearful, uncertain, docile, worthless, depressed, cynical, hopeless, and suicidal. Many people with low self-worth become addicted to alcohol or other drugs to suppress these deep, painful feelings.[25] With a low opinion of themselves, victims of abuse are also often desperate for loving attention, but incapable of loving or supporting others. This makes them poor parents.

Severe trauma affects some victims in a different way: they become violent and domineering. Some grow up to become violent criminals; some abuse their own children.[26]

In our society today, an alarming number of children are subjected to severe mistreatment in their homes. There are almost one million substantiated cases of child abuse or life-threatening neglect each year in the United States.[27] A federal advisory panel estimated that every year 2,000 infants and young children die from violence in the home and 140,000 (about 0.2% of all children) are seriously injured, leaving 18,000 children permanently disabled.[28]

Many parents do not physically hurt their children but still injure them psychologically by berating, bullying, fondling, rejecting, or ignoring them. Some children are traumatized by witnessing their parents venomously fight with each other.

Sticks and stones can break your bones, but words can break your heart.

Even children who grow up in stable, loving families may nevertheless face violence at school or in their neighborhoods. Children who are small, shy, or perceived as being different in some way are especially vulnerable to being ridiculed, threatened, isolated, or beaten by their peers.

Overall, a very large percentage of U.S. children are traumatized in some way. A recent survey of 4,000 adolescents (aged 12–17) found that 13 percent of females had been subjected to unwanted sexual contact, 21 percent of males and 13 percent of females had been physically assaulted, and 43 percent of males and 35 percent of females had witnessed firsthand someone being shot with a gun, knifed, sexually assaulted, mugged, robbed, or threatened with a weapon. An astonishing 72 percent of all the adolescents had directly observed someone being beaten up and badly hurt.[29]

Human Being

Contents: 100% Pure Human Being

Care Instructions: Hand wash with mild soap, towel dry. Regularly shower with warm affection. Leave self-worth intact. Use no bleach. Do not tumble, squeeze, or wring dry.

Trauma does not end with adolescence, of course. Adults suffer from domestic violence, rape, assault, murder, and war. In the United States in 1997, there were 18,200 murders, 300,000 sexual assaults, 1.8 million aggravated assaults, and 5.5 million simple assaults.[30] It is estimated that about 1.5 million women are raped or battered each year by their husbands or partners.[31]

Insults, threats, belligerence, and hostility are also prevalent in our culture. Moreover, we are all affected by the affront to dignity inherent in poverty, sexism, racism, classism, ageism, militarism, cultural chauvinism, and so on. Even relatively minor trauma can affect us — nibbling at our self-esteem, making us less flexible, inducing irrational fears and prejudices, and hindering our ability to address problems effectively.

Consequently, we all have been wounded in a variety of ways and have some emotional scars. Our injuries are buried deep within our psyches where they are difficult to fathom or remove. For example, most of us have long-term addictions of some sort — that is, we have compulsive, obsessive, fanatical, or inhibited behavior around alcohol, cigarettes, caffeine, sex, food, sweets, drugs, gambling, sports, shopping, TV, money, religion, or work that interferes with our ability to live good lives.[32]

Common Emotional Dysfunctions

- Irrationality

- Chronic rage

- Depression

- Low self-esteem

- Inhibitions, phobias

- Compulsions, obsessions

- Addictions

Emotional injuries usually dissipate with time, but the worst injuries can be quite persistent. Even many decades later, our most severe emotional wounds are often still raw and tender. When poked, they stir up a swarm of intense feelings — fear, grief, and anger — that may lead us to respond in seriously dysfunctional ways. Those people who have been most severely injured typically behave the worst, terrorizing and wounding others. But in times of stress, all of us tend to behave badly, often directing our anger at those who are unable to escape or fight back: small children. In this way, the disposition toward hostility and violence is irrationally conveyed from generation to generation.

A Sick Society

Even worse for society, those who share the same dysfunctional behavior or attitudes sometimes band together, develop a rationalization for their warped perspective, and promote their ideas to others. For example, some women — who have been severely brutalized by men — have argued that men are inherently evil brutes and that the only solution is to imprison or castrate them all. Because this perspective is so harsh and unusual, it seems bizarre to most of us.

The floggings will continue until morale improves.

However, in a similar fashion, people have concocted equally irrational ideas that are now widely tolerated. They have promoted their fears (xenophobia, homophobia, gynephobia, and so on), their angry responses (lynchings, corporal punishment, vengeance, militarism, hazing, hierarchical domination, cultural chauvinism), and their compulsions (smoking, gambling, drinking alcohol, using drugs, dogmatism). All of these are twisted, misdirected, and ineffectual responses to oppression. Nevertheless, they have become so pervasive that many of them are now institutionalized in schools, fraternities, churches, business, the military, and advertising. They are accepted as cultural norms.

Consequently, we live in a “sick society” with a culture dominated by racist, homophobic, vindictive, and violent ideas.[33] We are routinely bombarded by images and stories of brutality in graphic television coverage of automobile crashes, executions, bombings, and wars. Children learn spite and prejudice from their parents, other adults, and their peers. Fears are passed along through books, movies, television, and games.

Living in a crazy society makes all of us more fearful and isolated from one another. We are afraid to talk about our troubles for fear others will criticize us for our shortcomings and reject us. We are afraid to get too close to others for fear we will be forced to bear their problems and woes. We are afraid to disagree with others for fear they will show us to be wrong or assault us. We are even afraid of working with those with whom we agree for fear they will abandon us in trying times. This isolation and fragmentation make it difficult for us to get together to solve our mutual problems or to challenge the power elite. For this reason, elite interests often encourage individualism, social isolation, and fear of others.

Emotional Shackles

The greater the feeling of inferiority that has been experienced, the more powerful is the urge to conquest and the more violent the emotional agitation.

Clearly, it would be far easier to create a good society if everyone were happy and acted rationally. It would even be a bit easier to bring about positive change if just the majority of progressive activists were rational most of the time. But progressive activists share the same cultural conditioning and carry the same emotional baggage as others. Just like everyone else, activists are often self-righteous, arrogant, guilt-ridden, fearful, dogmatic, bureaucratic, irrational, depressed, dishonest, violent, vindictive, and fanatical. Many activists act out chauvinism and prejudice. They have addictions, compulsions, phobias, and deep feelings of self-doubt.*

* Lest my phrasing erroneously convey that I am somehow beyond irrationality or above petty foolishness, let me assure you that I am as crazy as the next person and I have done my fair share of acting out inappropriate and counterproductive behavior.

Emotional injuries often limit activists’ ability to listen to others, discern the truth, or lovingly support or even cooperate with others. Activists’ behavior is often patterned and rigid, making them unable to address new situations flexibly. More than a few activists crave raw, gut-level retaliation more than they desire positive change. When they spew these feelings and behaviors at other activists or manifest them in political action, they can wreak havoc on progressive change movements.

Madness takes its toll. Please have exact change.

Emotional baggage can also disempower activists. In difficult times, activists may erroneously feel their situation is as grim as it was during the worst days of their childhood when they were small, weak, and ignorant. Emotional injuries may also prevent activists from recognizing positive solutions or remembering them once discovered.

Though progressive activists seek change, their internalized fears may limit how much change they can imagine or tolerate. Even those who seek to change society down to the roots often fear changing themselves if it means risking the loss of the bits of security and control they have accumulated over the years.

I know that most men, including those at ease with problems of the greatest complexity, can seldom accept even the simplest and most obvious truth, if it be such as would oblige them to admit the falsity of conclusions which they have delighted in explaining to colleagues, which they have proudly taught to others, and which they have woven, thread by thread, into the fabric of their lives.

The nature of progressive change sometimes pushes activists towards especially bad behavior. Struggling nearly alone in a hostile world, they may huddle together for comfort, spawning the elitist and irrational behavior that Irving Janis calls “groupthink.”[34] Out of desperation or self-righteousness, a small number of change organizations employ some of the techniques of mind control to recruit, indoctrinate, and manipulate their members. Some activists — those especially vulnerable to manipulation because of emotional hurts — are drawn into these organizations.[35]

Some Symptoms of Groupthink

- Moral self-righteousness, elitism

- Pressure for conformity, vicious attacks on anyone who questions the group’s direction

- Self-censorship

- Single-mindedness and tunnel vision

- Suppression of bad news

- Insulation from outside criticism or ideas

Obstacle 4: Widespread Ignorance

Many people have limited knowledge about how society functions, and they passively accept conventional notions about democracy, free enterprise, addictions, personality disorders, and so forth. Most are also woefully ignorant of progressive alternatives. Hence, when people do learn about a useful alternative idea or method, they usually have little idea how to implement it in their own community.

This ignorance derives from many sources. Our public schools do a poor job of teaching people even the most basic information. For example, a 1992 national survey for the Department of Education found that more than 40 million adults (about 21% of the adult population) are illiterate or only barely literate.[36] A far greater percentage of students do not learn the basics of how our government and our economy operate. Few learn even rudimentary interpersonal skills.

The trouble with people is not that they don’t know, but that they know so much that ain’t so.

As noted in the sections above, this state of affairs exists in part because people tell each other erroneous ideas based on outmoded cultural norms or prejudice and pass these ideas on to their children. Moreover, elite interests actively use the news media to obscure their mechanisms of societal control and to circulate myths that perpetuate racism, sexism, classism, and so on. The elite also suppress information about progressive alternatives and belittle the ones that publicly emerge.

Clearly, it would be easier to create a good society if everyone had basic literacy and cooperation skills. It would be easier if activists were knowledgeable and skilled, but most progressive activists are also quite ignorant. Activists typically have limited progressive change experience, only a rudimentary understanding of how the world functions, and only dim visions of possible alternatives. Their ignorance and lack of experience often lead to inefficient, ineffectual, or even counterproductive change efforts.

Just because you watch a television set, doesn’t mean you know how to build one.

There are several reasons why most activists are inadequately prepared:

- Progressive change is one of the few complex endeavors in which it is assumed that, after watching others do it a few times, activists will be able do it themselves. Conceptually, progressive change seems straightforward, but to do it well requires extensive knowledge and skills. It is at least as difficult as building a skyscraper, programming a computer, performing surgery, or assembling a television. Yet it is often lumped in with other “simple” tasks like eating, washing dishes, or driving an automobile — and think how many years of our childhoods we spent mastering these tasks. Many of the skills required of activists are the same ones required of managers, planners, lawyers, social workers, and therapists — skills taught in multiyear college programs and honed through years of practice.

- As in the complex job of building a skyscraper, not everyone who works for progressive change needs to know how to do every task well — and some activists may only need to know how to do a few jobs. Clearly though, in each change organization, there must be some activists who understand and have experience performing each of the essential tasks. Furthermore, every activist must be able to work with other activists to coordinate their efforts.

- A large percentage of progressive activists have only worked for change a short time. It is often just a few months from the time an activist is first stirred to join a progressive organization and fight for change until the time she burns out and leaves.

Experience is a hard teacher because she gives the test first, the lesson afterwards.

- Since activists are generally not active for long, they often have little idea how to conduct a social change campaign. Many are unaware of historical change efforts (including how other activists overcame problems) and ignorant of theoretical analyses (like socialism, anarchism, feminism, pacifism, environmentalism, multiculturalism) that help explain larger political, economic, and cultural processes. Few have a chance to learn or develop the skills they need to work cooperatively with other people. Moreover, many harbor unexamined racist, sexist, xenophobic, or other reactionary attitudes. Moreover, many activists are young and so are inexperienced in basic life knowledge and skills.

- Since progressive organizations have little money, they usually focus narrowly on their primary change work and skimp on “extraneous” education. Often the educational opportunities they do offer focus on immediate tactical skills, not strategic planning or visionary thinking.

- Activists often favor quick action over study and reflection. Our consumer culture encourages shallow, short-term, reactive thinking and discourages skill-building and long-term planning. Activists often thrash each other with stories about horrendous calamities that they feel they must immediately correct. This fosters a movement culture of desperate urgency.

Ignorance Greatly Hinders Change

After suffering years of frustration, many progressive activists are content merely to “make a statement” instead of actually being heard or to be heard rather than having influence or to have influence instead of having decision-making power or to seize decision-making power rather than creating a true democracy of empowered citizens.

Activist ignorance creates a myriad of obstacles for progressive organizations. Here are just a few of the many ways progressive activists blunder primarily because of their ignorance:

• Hold Low Expectations and Feel Powerless

Like others in society, many activists accept that humans are inherently evil, greedy, or crazy or believe that humans cannot change very much. Others believe the claims of invincibility made by the power elite. Without knowing that ordinary people have generated major positive changes in society countless times before, activists believe they have little power.

Activists with these beliefs are likely to feel discouraged and hopeless even before they begin — they are programmed to fail. Feeling powerless, they often content themselves with inflicting some bit of revenge against a few powerholders. This may provide some immediate personal gratification, but it usually does not create much positive change.

• Hold Shallow Analyses or Goals

I don’t want you to follow me or anyone else… I would not lead you into [the] promised land if I could, because if I could lead you in, someone else could lead you out.

Activists often put forth simplistic, bumpersticker critiques of social problems and organize flashy, but inconsequential political demonstrations. Though these tactics can quickly generate a great deal of excitement and may seem to elicit quick responses, the potential for real, long-term change is usually limited.

If progressives can guide people to the left with shallow, flamboyant rhetoric, then manipulators like Ronald Reagan or Newt Gingrich — with their armies of propaganda specialists and immense advertising resources — can lure them even further to the far right. A progressive movement for change is quite fragile unless it can instill into a large number of people a deep understanding both of society’s problems and of progressive alternatives. There are no easy shortcuts.

• Focus Narrowly on Superficial Change or Social Service

Elite interests continually provide assurance that everything is fine — when social problems surface, the powerholders swear they need only rein in those few people who cheat, steal, or murder. Inexperienced activists often do not understand how deep and tangled are society’s problems and how extensive the changes must be to get to the root causes. These activists usually offer superficial or feeble reforms that, if implemented, would not count for much in the long run.

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root.