Inciting Democracy: A Practical Proposal for Creating a Good Society

Preface

Download this chapter in pdf format.

In This Chapter:

Why I Wrote This Book

As long as I can conceive something better than myself I cannot be easy unless I am striving to bring it into existence or clearing the way for it.

Imagine a society where no one lives in poverty. Imagine a society where it is safe to walk city streets at any hour of the day or night. Imagine a society where addiction to cigarettes, alcohol, and other destructive drugs is rare. Imagine a society where corruption in business and government is not tolerated and is quite uncommon. Imagine a society where murder, rape, domestic violence, and sexual abuse of children are extremely rare occurrences. Imagine a society that values the health and welfare of its citizenry more than anything else — more than power and more than money. Imagine a society where racism, sexism, and other irrational hatreds are virtually unknown. Imagine a society where every citizen is encouraged to understand and participate in civic affairs and most actually do. Imagine a society where people laugh freely, openly, and often. Imagine a society where people are glad to be alive.

If it were your job to create such a genuinely good society, what would you do? What resources would you need? How would you go about it?

These are the questions I address and try to answer in this book. As a long-time progressive activist and student of change, I believe it is possible to create a good society.* But I am also frustrated that those who have worked toward this goal over the last several hundred years have not yet succeeded, and I grow discouraged when it seems we will not achieve this objective anytime soon. I am sure many other people share my frustration and discouragement.

* I use the term “progressive change” to mean efforts to create a good society (as defined in Chapter 2). “Progressive activists” are people of goodwill who are actively working to create such a society and behave as described in Figure 4.2.

I wrote this book to confirm that it is possible to create a good society and to detail a way it could be done. By showing that it is possible, I hope to encourage us all to do the hard work necessary to accomplish it. By showing one practical way to do it, I offer one possible plan of action.

A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step.

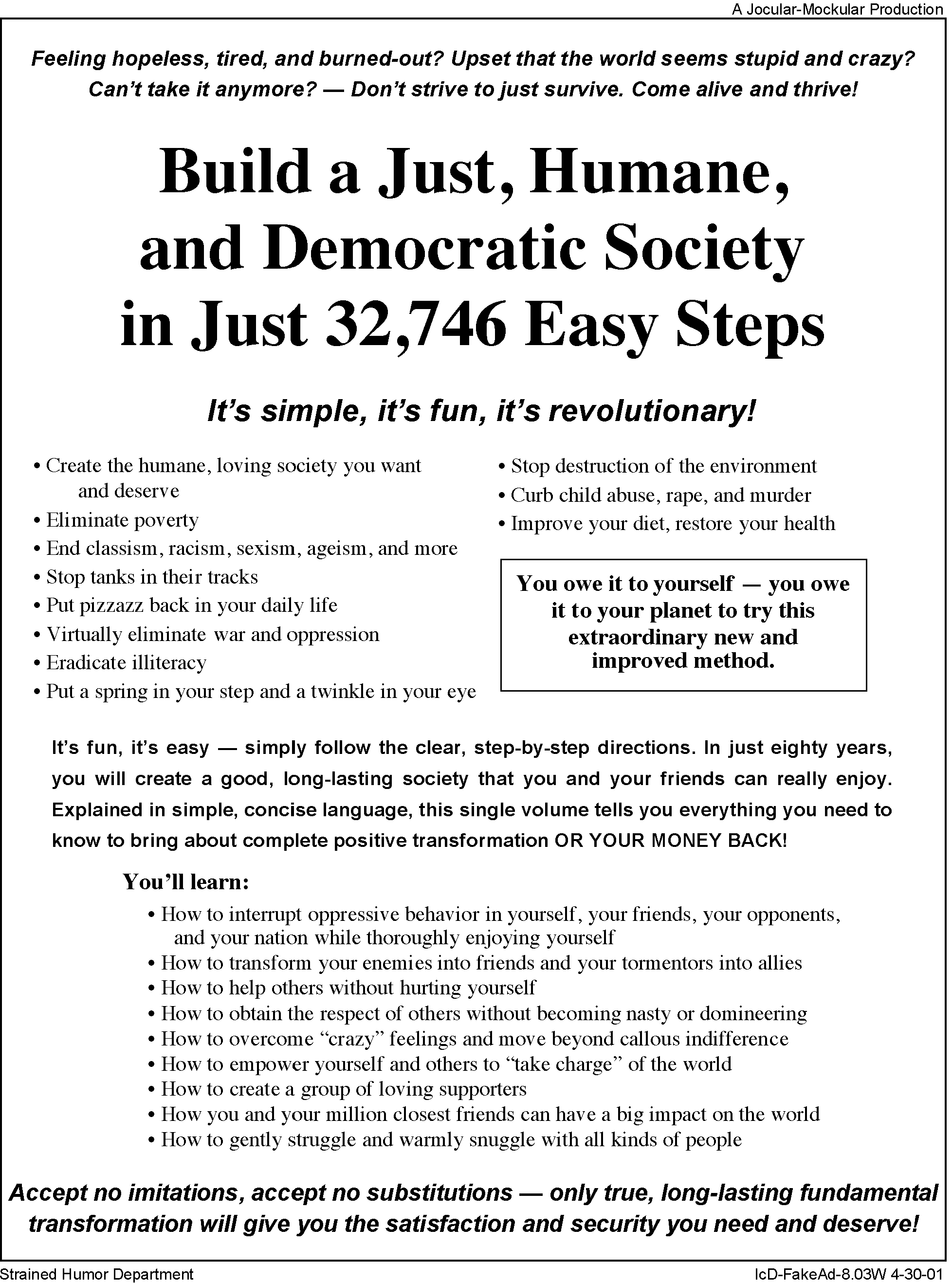

This book does not really detail the 32,746 steps necessary to build a just, humane, and democratic society as the facetious notice [below] proclaims. Rather, it explains what I mean by a “good society,” lays out the case for creating a good society, details the obstacles that hinder current efforts, and describes the factors necessary for a progressive change effort to overcome these obstacles. The book then describes what a progressive movement that hopes to bring about fundamental and enduring change might look like as it transforms society over eighty years. Finally, the book specifies a way to bring such a movement into existence by means of an education and support program. The last chapter is an annotated bibliography of books, magazines, radio programs, and web pages covering various social change topics.*

* I have tried to make this book readable and understandable to both experienced progressive activists and those new to social change work. For those who are less familiar with social change ideas and methods, Chapter 12 lists many of the books and magazines that have most informed and influenced me over the years. These works provide a good introduction to progressive social change.

When you have finished reading this book, I hope you are convinced it is possible to create a good society. Furthermore, I hope you are inspired to work towards this goal.

We can create a good society. Let’s do it!

A Vision

As a way to introduce these ideas, let me describe one possible scenario — first the finale, then the steps leading up to it.

An Educated, Broad-Based Movement

I visualize a time, perhaps forty years in the future, when there are a million people in the United States working earnestly for deep, far-reaching positive change. These progressive proponents are knowledgeable and skilled in the methods of individual empowerment, critical thinking, scientific investigation, liberating education, cooperation, participatory democracy, organization building, coalition building, respectful conflict resolution, emotional therapy, and nonviolent struggle.

As I envision it, these advocates are largely free from dependency on mainstream institutions. Instead, they support each other — and thereby protect themselves from being attacked or manipulated by powerholders or swayed too much by the dominant culture. They develop a wide array of alternative institutions based on progressive values — personal responsibility, freedom, democracy, respect for dissent, cooperation, altruism, and global stewardship.

There are those, I know, who will reply that the liberation of humanity, the freedom of man and mind, is nothing but a dream. They are right. It is. It is the American Dream.

With skills, values, and alternatives in hand, these million progressive advocates forcefully challenge existing institutions. They work together in strong, cooperative organizations. They pass on their ideas, skills, and methods to other people directly — without the distorting influences of the news media or other intermediaries — and they do so repeatedly over a long enough time to let the ideas sink in.

Over time, they influence vast numbers of people, build a variety of successful alternative institutions, and win many significant changes. By consistently and continuously challenging the old order over several decades, their successes in democratizing power compound at an ever-increasing rate. Each successive generation has incrementally less allegiance to the old order and greater understanding of the new. Moreover, elders wedded to the status quo pass away while young people grow up learning alternative skills and expecting progressive change.

With the active cooperation of a large portion of society and the passive acceptance of most of the rest, these million progressive advocates eventually surmount their own dysfunctional cultural and emotional conditioning and overcome the resistance of the power structure. At a time perhaps eighty years from now, they bring about fundamental and enduring changes in every aspect of society — political, economic, social, and cultural.

In this vision, I do not assume that progressive activists are any more intelligent or virtuous than activists today — only that they are more experienced, have more knowledge, and have greater skills than most current activists. I also do not assume they employ new techniques or strategies — although they might. Instead, I see an expansion of the best of what I have already seen — creative problem solving, potent nonviolent action, convincing alternatives, powerful emotional therapy, a supportive activist community, constructive alliance building, and so forth. Our best is very impressive and — multiplied severalfold — I believe it would energize activists and captivate the whole world.

Into each life some rain must fall.

Let me also say here, before I am misunderstood, that the good society I envision is not a blissful paradise, completely free of suffering or discord. There will always be pain and conflict in this world since (1) natural resources are limited, (2) severe natural events such as storms, earthquakes, and disease will always batter us, and (3) humans regularly make mistakes, often disagree with one another, have conflicting desires and interests, and always die eventually. However, in the good society I envision, our difficulties and sorrows are greatly reduced. Conflict is constrained and directed so that it does not demean or destroy people. Life is still hard in many of the ways it is now, but unlike now, people’s love and joy vastly outshine their woes and disputes.

The difficult is done at once; the impossible takes a little longer.

Could a million dedicated and skilled activists accomplish enough to bring about such changes? Honestly, I do not know. No one can really know what it would take. Still, I assume there is some level of effort that would be sufficient to bring about fundamental societal transformation. One million activists (about 1/2 percent of the U.S. adult population) working steadily for change over many decades seems like the largest effort for which we could reasonably hope. Based on my experience as an activist, my reading of history, and my careful study of this question, I believe it would also be sufficient. As the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the liberation of South Africa showed, dramatic positive change occurs more easily than we usually suppose. Our hopelessness is often much greater than is actually warranted by reality.

But How Is It Possible?

How could we get a million dedicated progressive activists to work together for change? Where would they get the experience and develop the skills they need to be effective? How could they get the support they need to live and work together?

Again, I see a possible scenario:

Every year, six thousand activists — who are wholly dedicated to making the world a better place — attend a yearlong education program where they learn skills and acquire practical experience. In this program, they develop a deep, broad view of how society currently works and how it could be radically better. They learn a variety of change skills as well as methods to avoid most of the pitfalls that now plague movements for progressive change. They also form bonds and develop trust with many other activists, thus establishing a source of deep, ongoing support. This enables each of them to work diligently for many years and ensures that, consistently, more than 25,000 of them continue to work at least twenty hours per week for fundamental change.

As I envision it, each of these skilled and dedicated activists is able to inform, support, and inspire about six other steadfast activists (150,000 total), each of whom is enabled to work at least three hours each week for change. Each of these activists, in turn, informs, supports, and inspires about six progressive advocates (900,000 total) who are able to work an average of one or two hours each week for change. Together, these progressive activists and advocates number more than a million and constitute a force for change that is several times more powerful than current progressive efforts.

How Does It Begin?

What would inspire thousands of people to attend this education program and then devote their time for many years to working for change and supporting other activists?

I see a few thousand people reading a book outlining this scenario. Inspired by the vision and convinced it might work, a few of them decide to make it a reality.

They develop a curriculum that can provide activists with the necessary skills and experience. Then they recruit thirty activists to attend the first education session. Pleased with the program, these early students tell their friends and colleagues. As the program becomes better known, it grows rapidly in size and then is replicated in fifty locations across the country. As more and more people learn of this change scenario and see it being implemented, they become more hopeful about the prospects for fundamental change. They develop an interest in attending one of the programs offered by this education network. Within a decade, thousands are enrolling, learning skills, supporting each other, and working together for change.

As anyone knows who has been part of a movement, a demonstration, a campaign, or a strike, struggles undertaken for the most limited and prosaic goals have a way of opening the most profound and lyrical sense of possibility in their participants. To experience even briefly a movement’s solidarity, equality, reciprocity, morality, collective and individual empowerment, reconciliation of individual and group, is to have a foretaste of the peaceable kingdom. . . . Once we have experienced solidarity, we can never forget it. It may be short-lived, but its heady sensations remain. It may be still largely a dream, but we have experienced that dream. It may seem impossible, but we have looked into the face of its possibilities.

The Structure of This Book

Chapter 1 describes the events and information that led me to believe it is possible to create a good society.

Chapter 2 clarifies the term “good society” by detailing some of the basic elements of such a society.

Chapter 3 investigates the obstacles that stand in the way of creating a good society. As I see it, these obstacles fall into five main categories: opposition from the power structure, destructive cultural conditioning, dysfunctional emotional conditioning, widespread ignorance (especially of progressive alternatives), and a scarcity of progressive resources.

Chapter 4 briefly reviews and evaluates the strengths and limitations of several historical strategies for fundamental transformation. This exploration uncovers eight crucial characteristics of effective fundamental change efforts, particularly that they be powerful, principled, and democratic. This chapter then outlines a strategy for transformation that consists of widespread education carried out by mass change movements.

Chapter 5 describes a four-stage strategic program for creating a good society that incorporates these characteristics. In the first stage, progressive activists would lay the groundwork by finding other activists, educating themselves, overcoming their destructive and dysfunctional conditioning, and forming supportive communities with other people of goodwill. In the second stage, they would gather support by raising others’ awareness about the possibility of creating a good society and the means to achieve it. They would also build powerful political and social organizations. In the third stage, they would use their strength to challenge vigorously both the power structure and dysfunctional cultural norms by using a variety of nonviolent methods. They would also develop attractive alternative institutions based on progressive ideals. In the last stage, they would diffuse change throughout all of society.

This chapter also outlines a democratic, bottom-up structure in which progressive activists would personally persuade and support others. A small number of dedicated activists would inform, support, and inspire a larger number of steadfast activists who would, in turn, inform, support, and inspire a much larger number of progressive advocates. Together, these activists and advocates would inform, challenge, persuade, and inspire everyone in society.

In this model, the most skilled and experienced activists would constitute a stable and reliable core of activists who would support other activists. They would also broaden other activists’ understanding of society, suggest innovative and effective ways to tackle difficult problems, and continue doing tedious or grueling work when other activists stray or falter. This would help to ensure that progressive organizations grow and prosper — and do not go off course, stagnate, or erupt in infighting.

The end of this chapter explains the dynamics of nonviolent struggle since this method would play a crucial role in the project and is often misunderstood.

Chapter 6 outlines a specific project we could undertake to implement this strategic program and especially to launch the first stage (the “Vernal Education Project”). This project would establish a yearlong education program for dedicated progressive activists. Designed to be inexpensive and practical, this education program would include facilitated workshops, self-study groups, internships, and support groups. It would offer activists a chance to experience and learn direct democracy, cooperation, emotional therapy, personal support, and a variety of social change methods while building strong bonds with other local activists. Students in this program would be encouraged to work for fundamental progressive change at least twenty hours per week for seven years after they graduated.

This chapter also describes how this education program could be replicated across the United States in fifty communities so that, eventually, six thousand students could attend a program every year.

The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today. Let us move forward with strong and active faith.

Chapter 7 shows that this education project could greatly bolster and support progressive change organizations. Calculations, based on reasonable assumptions about the growth of the project and the number of activists who might participate, show that after forty years there would be 25,000 graduates of the yearlong education program working at least twenty hours per week for fundamental progressive change, 150,000 other steadfast activists working at least three hours per week, and an additional 900,000 progressive advocates working a few hours per week. This would constitute an unprecedented force of over one million progressive proponents in all.

I estimate this many activists — most of whom would have much greater knowledge and skill than activists today — could generate an effort perhaps three or four times more powerful than current efforts for fundamental change. Dispersed all across the country, they could create an immense and sustainable movement for progressive change.

Chapter 8 tells a story that illustrates the many ways this education project could actually inform and support activists.

Chapter 9 first describes the unique dynamics of social change. It then shows how the Vernal Education Project could affect those dynamics and bring about fundamental transformation of society over eighty years.

Chapter 10 lays out a specific timeline for implementing this education project, especially the tasks required to launch it.

Chapter 11 summarizes the main points of the book and then responds to questions and concerns raised by critics.

Chapter 12 is an annotated list of useful books, articles, and other resources on progressive change.

Appendix A outlines some near-term policy changes that could move the United States towards becoming a good society.

Appendices B and C contain additional figures that I used to verify that this project is workable and feasible. Number-oriented people like me will probably find this interesting; most normal people can safely ignore these appendices without any regrets.

A witty saying proves nothing.

Cleverness is not wisdom.

I hate quotation.

Despite the warnings of Voltaire and Euripides and the disapproval of Emerson, I have also chosen to include throughout the text many clever sayings that I believe succinctly and memorably illuminate ideas. I hope they also add some spice to this treatise and make it easier to digest.

In places, I have also added my own side comments, distinguished by double bars above and below.

Ways to Read This Book

I have tried to make this book approachable and readable for many different kinds of people. The main proposal for the Vernal Project is presented in chapters 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10. The earlier chapters explain why I developed this particular proposal and not some other. Those readers interested in the objections raised by critics should turn to Chapter 11. Those who want to know what books have informed my thinking should turn to Chapter 12.

Those readers repelled by tables and charts should still be able to understand the thesis from reading the text. Conversely, those readers who are bored by expository text will probably be able to understand the thesis by studying the tables and charts. Those readers who prefer narrative text may choose to read only the vision section of the Preface and Melissa’s Story in Chapter 8.

Feel free to read this book in whatever way works best for you.

The Focus on the United States

This book focuses exclusively on fundamental progressive transformation of the United States, but not because I am xenophobic or parochial. I am fully aware of the innumerable interconnections between the United States and other countries, especially as the world’s economies become globalized. All parts of the world are now interdependent. Fundamental change in the United States is linked to change in the rest of the world.

I focus on the United States for three main reasons:

(1) The United States is the most influential country in the world — militarily, politically, economically, and culturally.

The United States maintains a military presence in more than 140 countries.

- Militarily: The United States is the only military superpower and has military bases and warships in every part of the globe. It is responsible for supplying more than half of all arms sold globally.[3]

- Politically: The United States dominates the United Nations Security Council, NATO, and other military and political alliances. Furthermore, through covert means, the CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies regularly manipulate governments and militaries around the world.

- Economically: The U.S. financial system comprises about a quarter of the world monetary system. A large percentage of transnational corporations are headquartered in the United States, and economic decisions made here affect other countries much more than the reverse. The United States dominates the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, and other global economic institutions.

- Culturally: U.S.-generated movies, television shows, advertising, business products (like computers), and consumer products (like Barbie dolls) pervade the rest of the world, propagating U.S. business and pop culture everywhere.

Because of this dominant position, positive change in the United States would likely engender positive changes in other countries. Moreover, without fundamental transformation of this country, the United States will probably continue to thwart positive change elsewhere.

My country is the world, and to do good is my religion.

(2) I grew up in this country, have lived here all my life, and am tuned into its culture. I feel I have some understanding of how it operates and how to change it in a positive direction. I have no similar comprehension of any other country or culture.

I assume the changes advocated in this book would be positive if applied to most parts of the world. But without a better understanding, it would be arrogant to tell others how their countries or cultures should change. If people of goodwill in other places find this book useful and applicable to their situation, I hope they will adopt it or adapt it in whatever way they believe best.[4]

He loves his country best who strives to make it best.

(3) I feel it is my primary responsibility to help change my own country and culture. Although there may be greater evils in other places, much must be changed here, too. As a responsible citizen of this country, I feel an obligation to make my country as good as it can be. Especially since I know that the United States is responsible for creating or bolstering much of the evil in other places, I feel a particular responsibility to change this country and curtail its support of oppression elsewhere.

A Note on Usage

Like every modern progressive writer trying to write clear English, I am hindered by the lack of any reasonable gender-neutral terminology. Where possible, I use neutral terms like “people” and “humankind” and rely on the universal singular (“one”) or the indefinite plural (“they”). However, sometimes I am forced, for clarity’s sake, to use a more specific singular. In most of these cases, I use the terms “she” and “her” in an effort to counter the traditional usage that implies that every important human is male. I considered using “person” and “per” — as in Marge Piercy’s novel, Woman on the Edge of Time — but feared this unusual terminology would be confusing or distracting.

I hope readers will understand that, regardless of the wording, I consider women and men equally capable and I desire political, economic, and social equality for all people.

Join the Dialog

Answers — 50 cents

Answers requiring thought — $1.00

Correct answers — $2.00

Dumb looks are still free.

After you have read this book, I would love to hear what you think. If you have the capability, it is easiest for me to respond to electronic mail. I will do my best to respond promptly.

Randy Schutt [Contact Info]

The Vernal Project website also contains a moderated dialog among all those who are interested in helping the project succeed. Please join this dialog. [Sorry, this is not happening.]

Next Chapter:

1. Background

Notes for the Preface

Note: References include a Library of Congress number — when available — to facilitate locating them in a research library.

Ronald Aronson, After Marxism (New York: Guilford Press, 1995, HX44.5 .A78 1994), p. 278.

This is Fact 205 gathered by PEN, the People’s Education Network.

The Defense Almanac can be found here:

http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/almanac/index.html

From 1995 to 1997, the United States sold more than $77 billion in arms, about 55% of the global total. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Arms Control, World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers 1998, Table 3, p. 165.

http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/bureau_ac/wmeat98/table3.pdf

See the summary (“Fact Sheet Released by the Bureau of Verification and Compliance, Washington, DC, August 21, 2000”) here:

http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/bureau_vc/wmeat98fs.html

See the complete report here:

http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/bureau_vc/wmeat98vc.html

From 1987 to 1997, the United States sold more than $280 billion in arms, about 5.2% of all U.S. exports for the period. The United States was one of only three countries in which arms exports represented more than 5% of its total exports. Israel and North Korea were the other two countries. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Arms Control, World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers 1998, Table 2, p. 158.

http://www.state.gov/www/global/arms/bureau_ac/wmeat98/table2.pdf

Dennis Altman, in Rehearsals for Change: Politics and Culture in Australia (Victoria Australia: Fontana/Collins, 1979, JQ4031 .A45) analyzes the prospects for progressive social change in Australia. He discovers many of the same obstacles there as I do in the United States, and advocates a similar kind of transformation that focuses on both cultural and political change. However, he also points out the many differences in culture and politics between the two countries.

IcD-Pr-8.08W 4-30-01

The Vernal Project

The Vernal Project