Inciting Democracy: A Practical Proposal for Creating a Good Society

Chapter 6:

The Vernal Education Project

Download this chapter in pdf format.

In This Chapter:

- Design Criteria for the Vernal Education Program

- Overview of the Vernal Education Program and Network

- Details of the Vernal Education Program

- A Vernal Student’s Time

- A Possible Vernal Curriculum

- Vernal Staffmembers

- Vernal Students

- The Vernal Education Network

- The Growth of the Vernal Education Network

- Vernal Project Finances

- Meeting the Design Criteria

- Other Educational Programs

- Carrying Out Stage 1 of the Strategic Program

- Notes

The last chapter described a four-stage strategic program for bringing about fundamental transformation of society. This chapter specifies a project to implement the first stage by developing a network of fifty educational centers across the United States. These centers would bolster the knowledge, skills, strength, and endurance of thousands of dedicated progressive activists each year, enabling them to support and educate hundreds of thousands of other activists (as described in Chapters 7 and 8). Together, all these activists would then be able to carry out the rest of the strategic program for fundamental change (as described in Chapter 9).

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.

In order to discuss this project and distinguish it from other education programs and other progressive change efforts, I have named it the Vernal Education Project. I chose the term “vernal” to evoke the image of a new, vibrant effort to revitalize society in a fresh, lively way, reminiscent of springtime.

ver•nal \vûr' núl\ adj.

1. Of, relating to, or occurring in the spring.

2. Fresh or new like the spring; youthful; energetic.

Please note that I have formulated this education program and the plan for its development in some detail to show that it is feasible to create such an enterprise.* I have spent a great deal of time considering all the necessary elements and testing many combinations of size and cost factors to come up with a self-consistent set that also seems both realistic and desirable. I believe this particular plan is sound, and I hope to work with others to implement it. However, this design is only one possible scheme among innumerable alternatives, and it is not set in stone. As the other developers and I work together to create the first education center and replicate it, we will invariably modify this plan in a variety of ways, probably changing it substantially.

* This chapter summarizes the design. Appendix B includes many additional figures that provide more extensive detail. Chapter 10 lays out a specific timeline for developing and implementing the design.

Moreover, other activists might admire some aspects of the Vernal Education Project but have other ideas about how to implement them. They might create their own independent endeavors. Inevitably, what actually unfolds will surely be quite different from what is described here. I present this plan simply to show there is at least one way to carry out such a project and to offer it as a first draft for a project.

Design Criteria for the Vernal Education Program

There are many classes, workshops, internships, and schools for progressive activists, but they are generally oriented toward beginning activists, toward a particular organization and its needs, or toward specific issues.* With its unique goal of fundamental societal transformation, the Vernal Education Project has a distinct orientation. To successfully implement Phase 1 of the strategic program for change outlined in Chapter 5, it must meet these criteria:

* A few of these educational programs are described at the end of this chapter.

• Offer a Wide-Ranging Education to Progressive Social Change Activists

When the only tool you own is a hammer, every problem begins to resemble a nail.

The Vernal Education Project must offer activists a broad and diverse education that lets them truly understand how the world now functions and shows them ways to transform all aspects of society.

• Vastly Increase the Skills, Strength, and Endurance of Activists

The project must provide a deep education to a large number of progressive activists. It must provide enough skills and offer enough support that activists have the strength and knowledge to effectively transform society. It must offer activists practical skills and useful information they can directly apply to their progressive change work. It must also provide enough support so that activists can carry on their work for many years.

• Facilitate the Development of a Cooperative Community

The project must support a cooperative community of progressive activists.

• Operate Efficiently

The project must produce substantial results, yet consume few resources. The overall cost must be quite low. The project must also supplement and bolster existing progressive change efforts, not detract from them or compete with them for funding or activist energy.

• Span the Country

The project must reach large numbers of activists all across the United States.

• Integrate with Activists’ Lives

The project must not disrupt activists’ lives. In particular, it must educate them without diverting them from their change work.

• Grow Rapidly and Continue for Decades

The project, starting from square one, must grow rapidly so that it can quickly reach a large number of activists. It must then be able to continue providing education and support to many activists for many decades.

• Conform to Progressive Ideals

The project must be consistent with progressive ideals in its structure, operation, and methods.

Philosophy of Education for Progressive Change

The last design criterion is especially important. Not only must the Vernal Education Project offer extensive education to thousands of activists, but it must do so in a way that is consistent with a good society. Traditional schools often view students as empty vessels into which wise teachers pour knowledge, filling them with The Truth. But this approach is actually more conducive to fostering a dictatorship of docile slaves than to building a democratic, cooperative society of empowered, responsible citizens. It assumes students are not only ignorant, but unable to think for themselves. It also assumes there is a single, absolute truth which teachers know and students must learn.

The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically… Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education.

Education is not filling a bucket but lighting a fire.

The world is infinitely complex. Important truths conflict with other truths, each valid in its way. For students truly to learn, they must have exposure to the full spectrum of ideas. They must also have the opportunity to weigh each new idea — evaluate its merits and flaws, relate it to their previous experiences, compare it to other ideas, explore its ramifications — and then wrestle with it to find an appropriate place for it in their own worldview. Furthermore, to become powerful citizens, students must practice using their own judgment, choosing their own directions, working cooperatively with others, and taking responsibility for their individual and collective choices.

I have tried to design the Vernal Education Program to offer a supportive environment for activists to explore a broad range of ideas about society and social change. Vernal students would be free to envision the kind of world they seek to create and free to choose whatever means they believe are best to get there. They would also have a safe place to try out their ideas and to practice using them with each other.

Overview of the Vernal Education Program

and Network

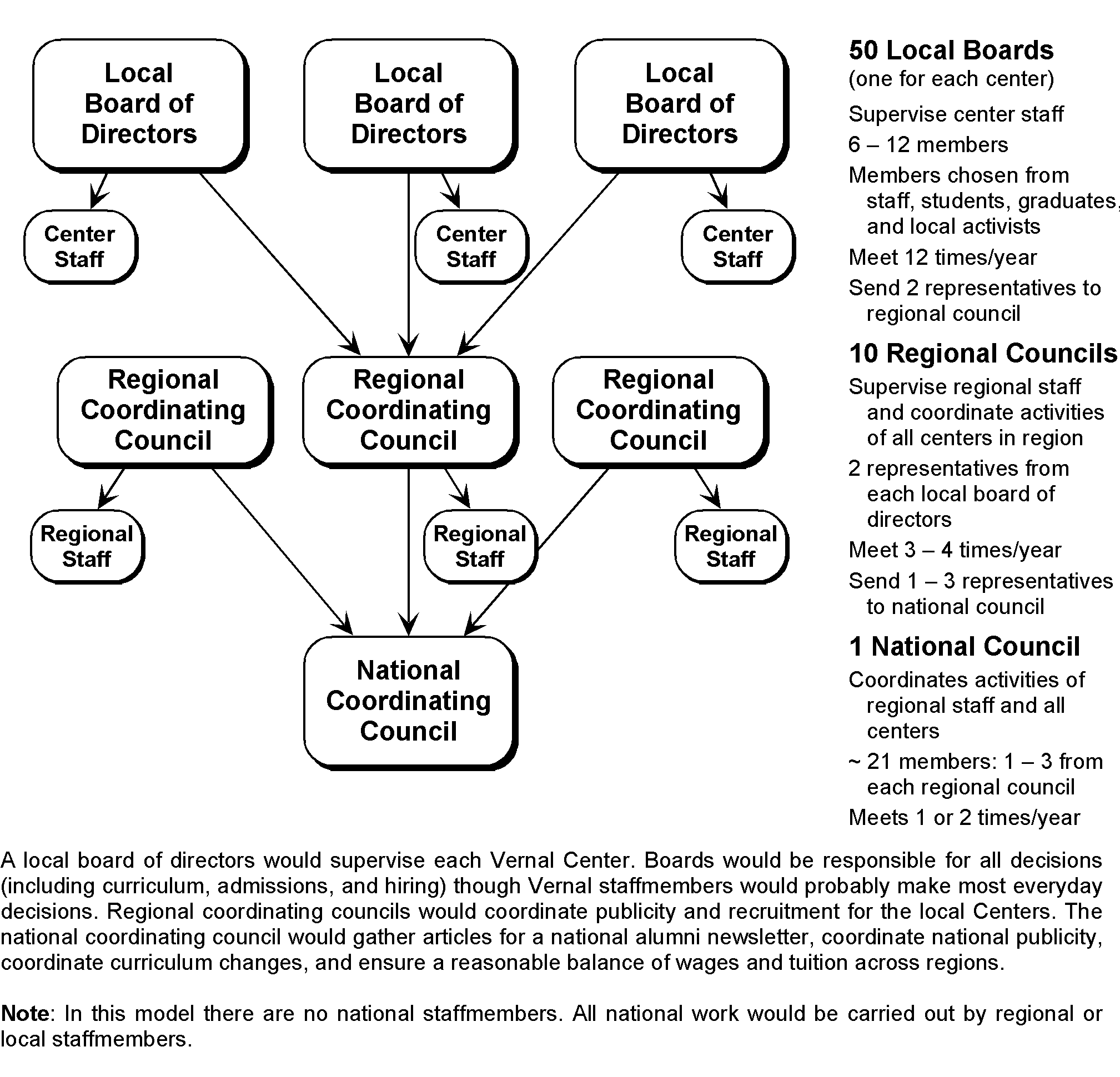

As I envision it, the Vernal Education Network would consist of fifty Vernal centers spread across the United States. Each Vernal center would be operated locally, but each would use a similar curriculum and similar educational methods. Each center would also coordinate with the others regionally and nationally.

The Vernal Program would be oriented toward activists with at least a year of social change experience and a desire to support other activists. It would offer Vernal students a wide variety of information, skills, and ongoing support so that after graduating they could do effective, powerful, progressive social change work. Each one-year session, about as intensive as the combination of two semesters of college and a summer job, would consist of these main parts:

- Student-run study groups

- Internships with existing social change groups

- Some independent social change work

- A small amount of social service work

- Self-study of current affairs

- A series of five staffmember-facilitated workshops

- Student-run emotional support groups or individual therapy

- Special events for Vernal students to socialize and network with each other

In addition, Vernal staffmembers would provide information about other educational resources and encourage students to partake of the ones they needed. Students would also be encouraged to maintain good physical health and to exercise regularly.

The first three months of the yearlong session would emphasize academic study of theory and history, though it would also include practical, hands-on learning. The next six months would include less theory and be more practical. The last three months would emphasize direct social change work. This last period would also pave the way for Vernal students to make a smooth transition to the change work they would do after graduating.

Students would live at home and do most of their studying, internships, and social change work in their home communities. In this way, their learning would be directly related to the change work they chose to do, and they would not incur any costs of going away to school. This would also significantly decrease the overall cost of the Vernal Program.

Each yearlong Vernal session would enroll about thirty students who lived near each other, learned together, and supported each other. Each session would be largely independent of others, though students would periodically socialize with students from other local sessions.

Four full-time Vernal staffmembers would work together in a team to simultaneously facilitate four sessions in the same area. Vernal staffmembers would provide overall guidance to students, arrange internships, facilitate the workshops, develop and update the curriculum, develop and update lists of local resources, and ensure that students were offered what they needed to become effective activists. Staffmembers would also provide administration for the whole program including recruitment and admission of students, collection of tuition, accounting, hiring new staffmembers, and so on.

To ensure the resources of the Vernal Program were used wisely, admission would be limited to activists who were already knowledgeable and experienced with social change and were committed to long-term progressive change. In particular, the program would be limited to those who intended to devote most of their time to nonviolent, fundamental social change for at least seven years after they graduated from the session and who were willing to support and educate other activists. The program would also be limited to activists who agreed to work to end their own addictive and oppressive behavior and to conduct all their social change work in an exemplary manner so as to serve as positive role models for other activists and the general public. In selecting students, Vernal staffmembers would also seek to assemble a group that reflected the diversity of the region in age, race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexual orientation, and so forth.

Once again, note that I have outlined a specific format for the Vernal program here, but it is likely to change as the developers of the Vernal Project test a variety of possibilities and see what works best.[1]

Some Definitions

Vernal Education Program — an educational program that would use a particular curriculum and methods to educate progressive activists

Vernal Session — a one-year course of study and mutual support that would involve thirty students who learned together

Vernal Staffmembers — experienced activists who would administer and facilitate Vernal sessions

Vernal Team — four full-time equivalent (FTE) Vernal staffmembers who would facilitate and administer four different Vernal sessions at a time; they would assist the study groups, arrange internships, research and prepare materials, facilitate workshops, mentor and support students, hire and prepare new staffmembers, and administer the whole program; typically, a team would launch a new session every three months

Vernal Center — another name for a Vernal team located in one metropolitan area; note that a Vernal center would be conceptual, not physical — the Vernal team might not even have an office

Vernal Education Network — the network of fifty Vernal centers around the United States.

Regional Administrators — Vernal staffmembers who would provide additional administrative help to Vernal centers and provide coordination between centers; they would not be associated with a particular center, but would work with all the centers in a region

New Staff Preparers — Vernal staffmembers who would help to hire, support, and teach new staffmembers how to do their jobs; these staffmembers would also not be associated with a particular center, but would work wherever necessary across the country

Vernal Students — activists who enrolled in a Vernal session

Vernal Graduates — activists who graduated from a Vernal session

Very Active Graduates — Vernal graduates who saw progressive social change as their primary focus and worked at least twenty hours per week for fundamental change

Less Active Graduates — Vernal graduates who spent less than twenty hours per week working for progressive change — these people would probably spend some time working for social change, but their primary focus would be on some other activity (such as pursuing a traditional career or raising a family)

Vernal Activists — all Vernal students, very active graduates, and less active graduates who were working for progressive change

Vernal Education Project — the effort to create and sustain the Vernal network and to support Vernal activists in their progressive social change work

Note that I have deliberately chosen not to use the term “school” since this word often conjures up images of classrooms, grades, and obedience to authority — the Vernal Education Program would have none of these. I have also chosen to avoid traditional terms like “training,” “instruction,” and “teachers” to escape the negative connotations sometimes associated with these words.

Mission of the Vernal Education Program

The main mission of the Vernal Program would be:

- To pass along the lore of social change to activists — including social change history, social change skills, political theories, critiques of current society, visions of alternatives, and methods for imparting change skills to other activists

- To develop activists’ critical thinking skills

- To provide progressive activists with a chance to experience and practice the skills of direct democracy, consensus decision making, individual and collective responsibility, cooperation, conflict resolution, systematic problem solving in a group, nonviolent struggle, and other methods of progressive social change

- To spread social change skills widely across the entire range of movements for progressive change and across the United States

- To create a community of activists sympathetic with one another’s perspectives who could support one another emotionally and physically

- To provide a safe forum for diverse activists to discuss and debate social change ideas with their colleagues

- To sustain progressive activism, especially during hard times

- To inspire hope by serving as a bright beacon of progressive ideals, exemplary moral values, and effective social change shining out through the darkness of conventional society and politics

- To inspire hope by producing enough Vernal graduates who would work assiduously for change so that each graduate would know she was not alone

We have come out of the time when obedience, the acceptance of discipline, intelligent courage and resolution were most important, into that more difficult time when it is a person’s duty to understand the world rather than simply fight for it.

Details of the Vernal Education Program

After studying a variety of progressive change schools, I have tried to craft the Vernal Education Program to convey the greatest amount of social change knowledge to new activists using the fewest resources possible. To ensure the program would be both useful and inexpensive it relies on: (1) having students teach each other, (2) tapping the educational resources of existing social change groups, and (3) avoiding the costs of renting, buying, and maintaining campuses or buildings. The design also incorporates a wide variety of educational methods.

At the heart of the Vernal Program would be direct, hands-on social change work, supplemented by reading, discussion, research, writing, experiential exercises (roleplays), and some lecture presentations. Though the program would include social change theory, it would focus primarily on the practical aspects of applying this theory to real social change work — especially to the work that Vernal students were presently engaged in or would be soon after graduating. As I envision it, the program would have these ten main parts:

1. Study Groups

Study groups would be the primary means for Vernal students to acquire basic knowledge about the history and theory of progressive social change. Students would conduct study group meetings in their own homes. Each study group would comprise five to nine students who lived in the same neighborhood or city. The students in four or five study groups located near one another would comprise a Vernal session of about thirty students.

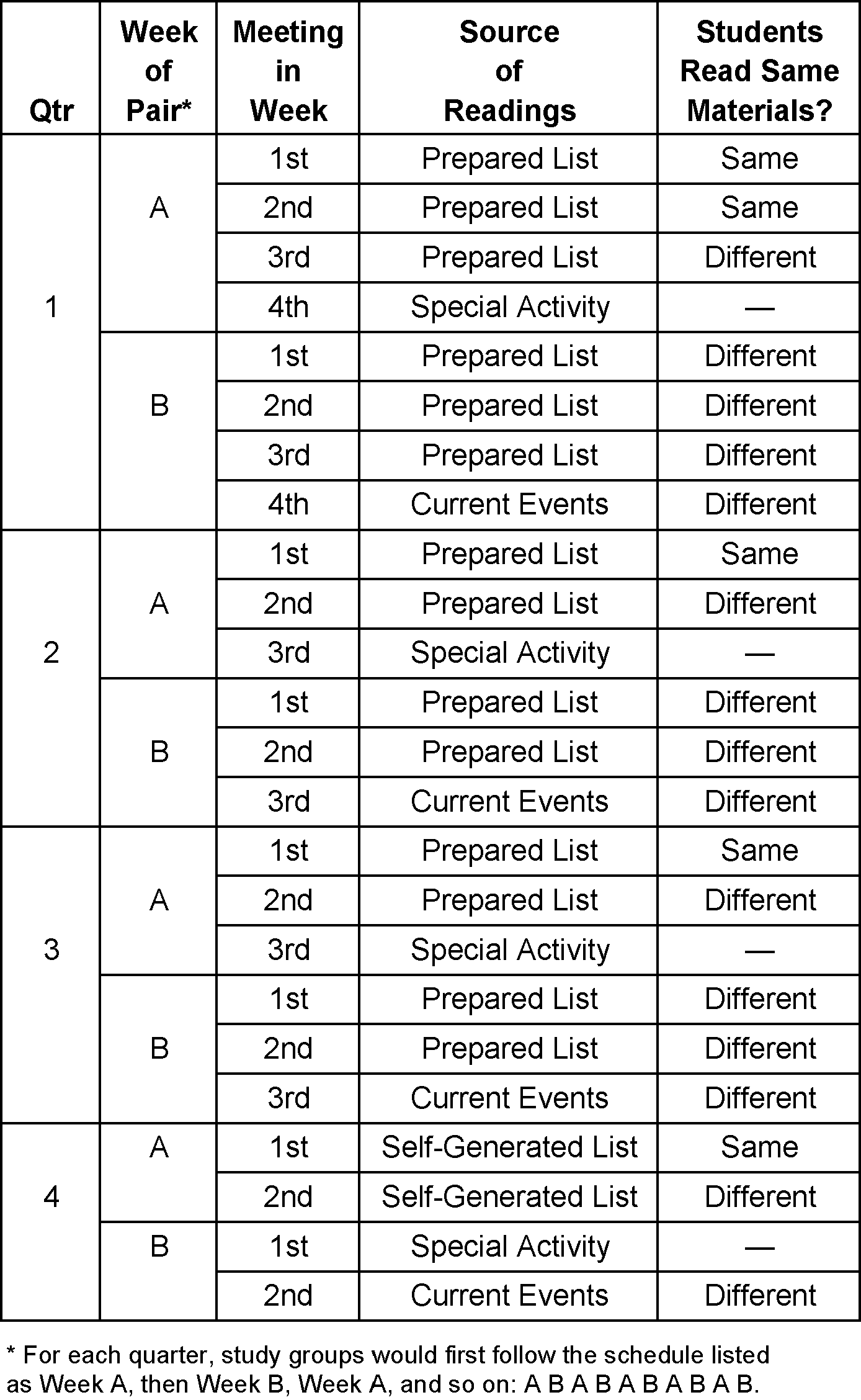

Students would meet in their study groups for three hours at a time (see Figure 6.1 for a typical meeting agenda). They would meet four times a week for the first three months of their session (the first quarter), three times a week for the next six months, and twice a week for the last three months except when they were attending workshops (as described below) and during holiday and vacation periods. Following this schedule, Vernal students would meet 116 times in their study groups.*

* In each thirteen-week quarter, students would have one week of vacation and two weeks of workshops (three in the first quarter). Hence they would meet in their study groups for nine weeks the first quarter and ten weeks in each of the other three quarters. Figure B.3 in Appendix B has more detail.

[Picture of Figure 6.1]Figure 6.1: A Typical Agenda for a Study Group Meeting

During the first nine months, students would mostly follow an established curriculum of study topics prepared by Vernal staffmembers (see the illustrative outline of topics below in the section entitled “Study Group Topics”). In preparation for most meetings, students would read an appropriate book or set of articles. Then they would discuss these readings at the study group meeting. Some readings would be introductory in nature for those relatively new to the topic, while others would appeal to those who were already knowledgeable.

Interest is the greatest teacher.

Students would focus on several different major topic areas, spending a few weeks on each one. At the beginning of each major topic area, every student would read the same book or set of articles. For the rest of the time devoted to the topic area, each student would choose and read a different set of materials and make a concise five minute presentation to the other students describing the reading and its most important ideas.[2] In some meetings, students would choose an article or two from a recent magazine or newspaper that covered some current event (on any topic), read it, and present it to the other students.

Each student would read approximately 50–150 pages (and, perhaps, listen to a recording, watch a video, or explore a website) in preparation for each study group meeting. Every few weeks, students would also read supplementary materials and prepare brief written summaries for the other students. On average, students would probably spend about six hours preparing for every study group meeting.

During some study group meetings, students might analyze a particular problem using a force-field chart, web chart, or problem-solution-action chart.* Alternatively, they might engage in a values clarification exercise, do a campaign simulation exercise, or play a simulation computer game. At other meetings, students might listen to recordings, watch videos, or invite experienced activists to talk about their work. Students might also take field trips to visit nearby social change organizations. At some meetings, particularly when world events were especially exciting, students might decide to forgo the regular topic and instead discuss current affairs.

* Force-field chart: a brainstormed list of the forces supporting and opposing a particular change campaign.

Web chart: a diagram of the various causes of a particular social situation and the causes of those causes, extending out to all the root causes.

Problem-solution-action chart: a brainstormed list of social problems (in a particular issue area), then possible solutions to one of the problems, then possible actions to realize one of the solutions.

For a more detailed description of these exercises, see Philadelphia Macro-Analysis Collective of the Movement for a New Society, Organizing Macro-Analysis Seminars: Study and Action for a New Society (Philadelphia: New Society Publishers, 1981).

For the last three months of the session, each study group would research a particular issue area of interest and then cooperatively create a reading list on this topic. Students would be encouraged to choose a topic related to the social change work they were doing or were planning to do. After graduating, they could then use this list as the basis for self-study groups for other (non-Vernal) activists working on this topic as well as by other Vernal groups.

During the last three months, students might also spend some time helping to facilitate other beginning Vernal sessions held nearby and to mentoring new students. This would give them a chance to practice what they had just learned from their Vernal studies about helping others learn.

Figure 6.2 shows a possible study group schedule. In this schedule, students would focus on each topic for two weeks. For the first part of the first week (designated week “A” here), all of the students would read and discuss the same materials. For the rest of the two week period, each student would study a different reading, present it to the other students, and discuss it. At the last meeting of the second week (week “B”), each student would choose a recent article on a current event, present it to the other students, and facilitate a discussion of it. One meeting of each two-week period would be completely devoted to a special activity such as doing an exercise, watching a video, having a guest speaker, going on a field trip, or playing a simulation game.

[Picture of Figure 6.2]Figure 6.2: A Possible Study Group Schedule

Following this schedule, students would cover fifteen staffmember-chosen topics (the first topic for only one week) and one topic they had chosen on their own. Of the total 116 meetings, they would read and discuss staffmember-suggested readings at 67 meetings, read and discuss readings they had put together themselves at 10 meetings, read and discuss articles on current events or issues at 19 meetings, and do a special activity at 20 meetings. They would all read the same materials at 24 meetings, and they would read different materials at 72 meetings.

Please note again that this is just a possible plan — Vernal students could adjust the schedule to whatever best suited them, or they might choose to arrange a completely different program of study.

Note also that students would learn not only from reading, discussing social change ideas, and engaging in exercises, but also by working cooperatively to plan their study group activities. A Vernal staffmember would periodically attend study group meetings to see how things were going and to offer information, support, and direction. As I see it, a staffmember would typically visit once a week at the beginning and then once or twice a month for the rest of the year.

2. Internships

A second key part of the Vernal Program would be internships with several existing social change organizations in or near the students’ home community. Internships would offer Vernal students practical, real-world experience and regular contact with experienced mentors.

Students would have a different internship in each of the second, third, and fourth quarters of the session. Each internship would require twelve hours of work per week for ten weeks (skipping weeks with workshops). If possible, sponsoring organizations would pay students a modest stipend. However, most groups could probably not afford to do so.

Groups offering internships would be encouraged to allow students to read the group’s literature, attend its planning meetings, and participate in the group like any volunteer or new employee. Students would perform day-to-day work for the organization and also work on at least one instructive project. Typical projects might be:

- Researching and writing an article for publication or a leaflet to be used in canvassing

- Sending out press releases and following up with reporters

- Arranging to speak to several student, labor, church, or civic groups and then doing it

- Arranging a series of film showings

- Helping plan a rally, conference, or fundraising event

- Lobbying for a bill

By carrying out a real project, students would advance the work of the sponsoring group, gain a direct understanding of the work that the group performs, and learn the skills necessary to do their project. After ten weeks, students should have a good understanding of how the organization works, why it is configured the way it is, and why it works for change in the way that it does.

Many organizations would probably seek to offer internships. Vernal staffmembers would select groups that could provide a good learning experience for students, including a supervisor/mentor who could meet regularly with the student to review the student’s work and learning experience. To ensure internships were educational and satisfying, each student would also have a designated Vernal staffmember to confer with about any problems. Whenever problems arose, the Vernal advisor would advocate for the student and negotiate solutions with the sponsoring group.

Typical organizations offering internships might be locally based peace, justice, or environmental groups; neighborhood groups; local groups working against racism, sexism, ageism, or heterosexism; chapters or affiliates of national groups such as the ones listed in Figure 6.3; public-interest law firms; church social action committees; labor unions; social change funding foundations; political campaigns; and progressive publications. Students might also work for social service agencies that have a social change component such as battered women’s shelters. Students would work primarily with locally based groups but might have one internship with a national- or state-level organization if it were nearby.

Figure 6.3: Some Progressive National Organizations

with Local Offices, Chapters, or Affiliates

| War Resisters League (WRL) | Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) |

| Peace Action (formerly Sane/Freeze) | Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC) |

| Jobs with Peace (JwP) | Greenpeace |

| Women’s Action for Nuclear Disarmament (WAND) | The Sierra Club |

| 20/20 Vision | Citizens Clearinghouse for Hazardous Wastes |

| Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) | The Toxic Waste Coalition |

| The New Party | Citizen Action |

| The Greens / Green Party | Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs) |

| Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) | The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) |

| The National Organization for Women (NOW) | The National Urban League |

| The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) | The Gray Panthers |

| Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) | The National Council of Senior Citizens |

| Clergy and Laity Concerned (CALC) | Children’s Defense Fund |

| New Jewish Agenda | Stand for Children |

| Interfaith Impact for Justice and Peace | Act Up |

| Common Cause | Food Not Bombs |

| The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) | Bread for the World |

| Alliance for Democracy | Amnesty International |

| National Lawyers Guild | United Nations Association |

| The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN) | Physicians for Social Responsibility |

In areas where there were no suitable organizations to offer internships, students might work with an individual activist who agreed to serve as a mentor. Alternatively, students might start a new organization to fill the obvious void in their area.

Students would be encouraged to work both with familiar organizations they found especially interesting and with those that were unfamiliar. By choosing three dissimilar groups, students would see several ways of working for social change, observe a variety of internal processes, and hear a range of social change philosophies. By discussing and comparing their experiences with other students, they would have exposure to even more perspectives.

For example, a student especially interested in legislation to advance women’s issues might intern first with the local NOW group and speak before civic groups about the need for day-care centers and battered women shelters. In the next internship, she might choose a very different area and work with a group trying to stop weapons shipments to repressive countries by blockading the local port. Finally, she might work with a campaign to elect a progressive Congressmember. At study group meetings she might learn from the experience of one student who helped a lawyer draft a lawsuit to force the clean-up of a local toxic waste dump and from another student who worked with a community organization demanding a police review board. At a workshop, she might compare her experiences with her support buddy who researched progressive tax-code legislation for a progressive party.

Internships would benefit both students and the sponsoring organizations. Students would have direct, personal exposure to a variety of groups and their different social change styles and philosophies. In turn, students would contribute a great deal of inexpensive assistance to the sponsoring organizations. The 120 hours of work students would contribute should be quite valuable since students would already be somewhat skilled and experienced — they would have had at least a year of prior experience before enrolling plus whatever they had learned from the Vernal Program up to that point.

Moving from one internship to the next and discussing their experiences with students who were interning in other places would produce another benefit: students would informally “crossbreed” ideas from one group to another. This could help create bonds between groups and might expedite formation of a broad coalition at some later juncture. Through their internships, students might also discover organizations with which they wanted to continue working after completing their Vernal education.

3. Social Change Work

In addition to their internships, students would work for progressive social change as a regular, ongoing member of a local change group. Typically, this would be a small, self-governing, grassroots group working on a particular issue of great interest to the student, such as reducing military spending, increasing funding for poverty programs, cleaning up toxic wastes, changing the local tax code, or exposing racist bank policies. For many students, this group would be the one with which they were working before enrolling in the Vernal Program or the one that they intend to work with after graduating. In areas where there were no suitable social change groups, students would start one.

As I envision it, students would work with their local group about three hours per week for the first three quarters and then, to help prepare them to work for change after they graduated, for nine hours per week during the last quarter. Working for only three hours a week, students would probably not be the most active or effective members of their groups. Still, they would probably partake of the full experience. Grappling with concrete problems in a real group would provide students with countless questions for discussion in study group meetings, workshops, and support group meetings. Working with a group would also provide students with an opportunity to immediately try out ideas and techniques as they learned them. During the last quarter, when they would be working nine hours per week, students should have time to accomplish a good deal of social change work.

4. Social Service Work

To be in good moral condition requires at least as much training as to be in good physical condition.

Besides their social change internships and work for change, students would volunteer a small amount of time during the first quarter (a total of 24 hours) for a social service organization helping poor, homeless, disabled, sick, hurt, or emotionally disturbed people, providing assistance to children or infirm elders, or repairing damage to the natural environment. Direct service would introduce students to some of the unmet needs of society and to the organizations that provide assistance. Direct service would also encourage understanding of and altruism towards people in need. Moreover, this service work would help to establish a positive reputation for the local Vernal center.

Though important to society, this part of the Vernal Program would be restricted to a relatively small amount of time in just the first quarter since the program primarily focuses on social change and there is not time to do more.

5. Self-Study of Current Affairs

As part of their Vernal education, students would be expected to stay informed about current affairs and social change movements through reading, listening to the radio, and browsing the internet for a total of six hours per week. Students would typically read a good daily newspaper or a weekly news magazine as well as three to six weekly or monthly progressive and alternative newspapers, newsletters, or magazines. They might also listen to a daily news program on the radio or read articles and action alerts on web pages or receive them through email. As described above, students would also spend some time in their study groups discussing current affairs.

6. Workshops

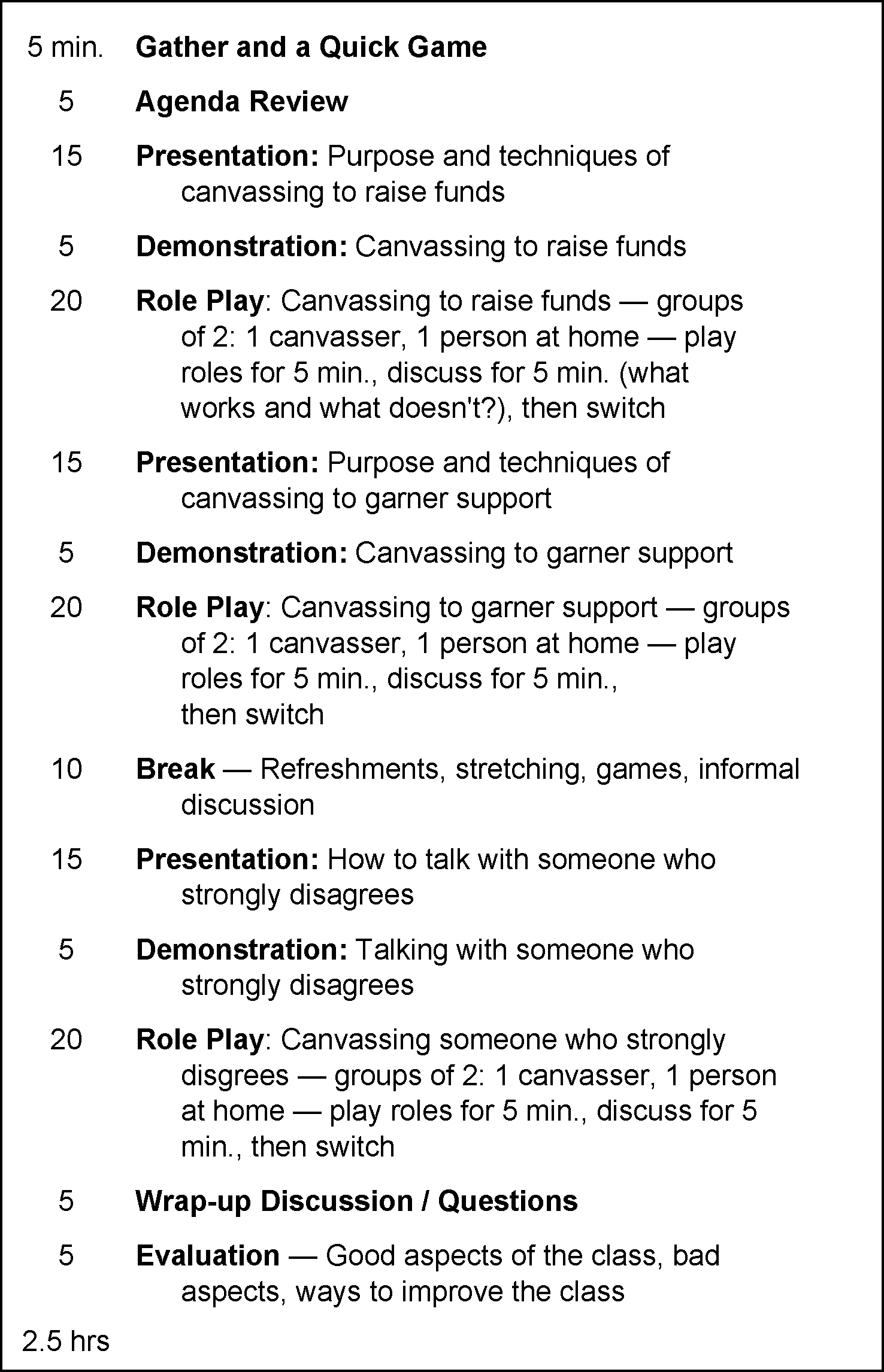

As I envision it, over the course of the yearlong Vernal session, the thirty students enrolled in that session would attend together a series of five staffmember-facilitated workshops: a five-day orientation workshop plus four ten-day workshops. Every day of each workshop would have two or three class periods each two-and-one-half hours long. During these classes, Vernal staffmembers would present basic information on important social change topics, answer questions, facilitate discussions of ideas and solutions, and facilitate experiential exercises (role plays, simulations, games). Experiential exercises would take up the bulk of the time in each class. Figure 6.4 shows an example of a typical agenda for one of these classes. The five workshops would include a total of eighty of these classes.

[Picture of Figure 6.4]Figure 6.4: A Typical Agenda for a Workshop Class — Canvassing

For each of the classes, students would receive an extensive set of notes — a simple textbook of two to ten pages — on the topic covered. These notes are described more fully below.

One class time during each workshop would be devoted to a structured discussion and evaluation of study group topics, internships, social change work, and the rest of the Vernal Program. Based on this evaluation of the session, Vernal staffmembers would then address any problems and, in conjunction with the students, modify the program as necessary.

Some time each day would be left open for students to relax, play, exercise, study, and informally discuss social change and swap their experiences. There would be a social party held one evening during each workshop for students to dance and sing together. Students would also have a designated time each day to confer and commiserate with a “support buddy” about how things were going for them — a chance for each student to express her joys, fears, and emotional upsets.

He that is taught only by himself has a fool for a master.

These workshops would provide an efficient way for Vernal staffmembers to quickly convey to students a great amount of knowledge and skills. They would also bring Vernal students and staffmembers together in a close, structured, yet relaxed environment — facilitating friendship, bonding, and honest political discussion. This would help to spawn a true community of activists.

Workshops would be held in rented or donated facilities — preferably inexpensive retreat centers in beautiful, natural environments. These retreat centers might be summer camps, ski lodges, or college campuses. To hold down costs, students would help with food preparation and cleaning. Also, if possible, students and staffmembers would perform some physical labor for the retreat center (construction, maintenance, cleaning) in exchange for reduced rent. Besides lowering costs, this work would help strengthen bonds between students and teach cooperation skills.*

* If there were no work available for students to do, they might engage in some other group activity such as a group hike.

7. Health and Exercise

Social change work is difficult and often physically demanding. It usually requires great energy and stamina. Many activists are hindered in their work by health problems, especially as they grow older. The most effective activists are vigorous, healthy, and fit.

True enjoyment comes from activity of the mind and exercise of the body; the two are ever united.

As I see it, staffmembers would set a good example with their own behavior, and they would also encourage students to exercise regularly, eat healthy food, get adequate sleep, bathe, clean their teeth regularly, and otherwise maintain a healthy lifestyle. At workshops, staffmembers would ensure that students had ample opportunities to engage in vigorous physical activity. They would prepare nutritious meals from healthy ingredients and ensure healthy snacks were always available. Every workshop class and study group meeting might also include some stretching or light exercise.

8. Support Groups/Therapy/Body Work

Social change work usually requires a great deal of intense, personal interaction — cooperating with, challenging, caring for, and struggling with all kinds of people. To be effective, activists must maintain good emotional health and minimize their own ineffectual, inappropriate, or oppressive behavior. The most effective activists are energetic, confident, clear thinking, focused, and humorous, even in difficult circumstances. To provide emotional sustenance, students would have a chance to meet weekly or bi-weekly in support groups to talk about how things were going and to get encouragement and nurturance from other students in a safe atmosphere.

A Possible Support Group Meeting Agenda

Members of a support group typically divide up the total time they have together so each person has a specific period in which to engage in whatever activity she finds most useful. In her designated time, a member might talk about a recent difficult experience or a problem she is struggling to overcome. She might ask the other members to support her by simply listening attentively, or she may want the others to ask questions, to give her suggestions, to challenge her ideas, or to praise her for her hard work. For comfort, she might want to be complimented, touched, or held.

To focus specifically on achieving her social change goals, she may find it useful to answer the following set of questions:

- How have I worked for positive social change since the last meeting? What worked well? What hasn’t worked so well? How might I have done it better?

- Considering the current situation, what should be done next to bring about positive social change?

- What are my specific plans to bring about change in the next few days, weeks, or years?

- What concerns, fears, or inhibitions do I have about implementing these plans?[3]

Let him that would move the world, first move himself.

Early in the year, students would learn about a variety of personal transformation techniques (such as journal writing, solitude, meditation, yoga, massage, peer counseling, therapy with a counselor). Staffmembers would encourage each student to choose a helpful personal transformation practice and engage in it regularly.

9. Socializing and Networking

Once a month, students and staffmembers would plan a potluck dinner for all the students in all the local sessions in the area. At these dinners students could meet each other and socialize, sing, dance, and discuss their change work. Students would also be encouraged to set up additional social networking meetings, parties, or celebrations every three or four months with other students and other activists with whom they worked. “Gathering the clan” would remind them that they are not alone in their change work and would provide a chance for activists with diverse backgrounds and orientations to meet in a friendly, informal atmosphere.

After graduating, Vernal activists would likely want to continue to socialize with, support, and learn from each other. They would probably stay in touch by arranging social events, meetings, conferences, or reunions with other graduates.

10. Other Resources

Most communities have many additional educational resources that are useful for activists. These include:

- Workshops for nonprofit organizations concerning fundraising, office management, board development, computer use, and so on

- Workshops on mediation and conflict resolution

- Various classes and workshops focused on personal transformation and emotional counseling therapy — assertiveness training, Parent Effectiveness Training, 12 Step Programs for overcoming alcoholism and other addictions, Re-evaluation Counseling, meditation, yoga, aikido, tai chi, and hundreds of others.

Rather than trying to duplicate any of these resources, Vernal staffmembers would try to evaluate, list, and briefly describe a wide range of local resources. They would recommend resources that seemed especially pertinent, useful, and inexpensive and offer tips on how to evaluate them so students would not waste their time or money.

Synergistic Learning

Individually, each component of the Vernal Program would enable students to learn and practice crucial social change skills. Combined, these components should be even more educational. Students could immediately apply what they learned from study groups, self-study, and workshops to their social change efforts and see how these ideas worked in practice. They could bring questions and problems from their internships, social change work, and social service work to study group meetings and workshops where staffmembers and other students could provide insight and guidance. Students could compare their experiences in different internships and social change groups. Throughout, they would be surrounded by other activists offering insight, support, and encouragement.

A Vernal Student’s Time

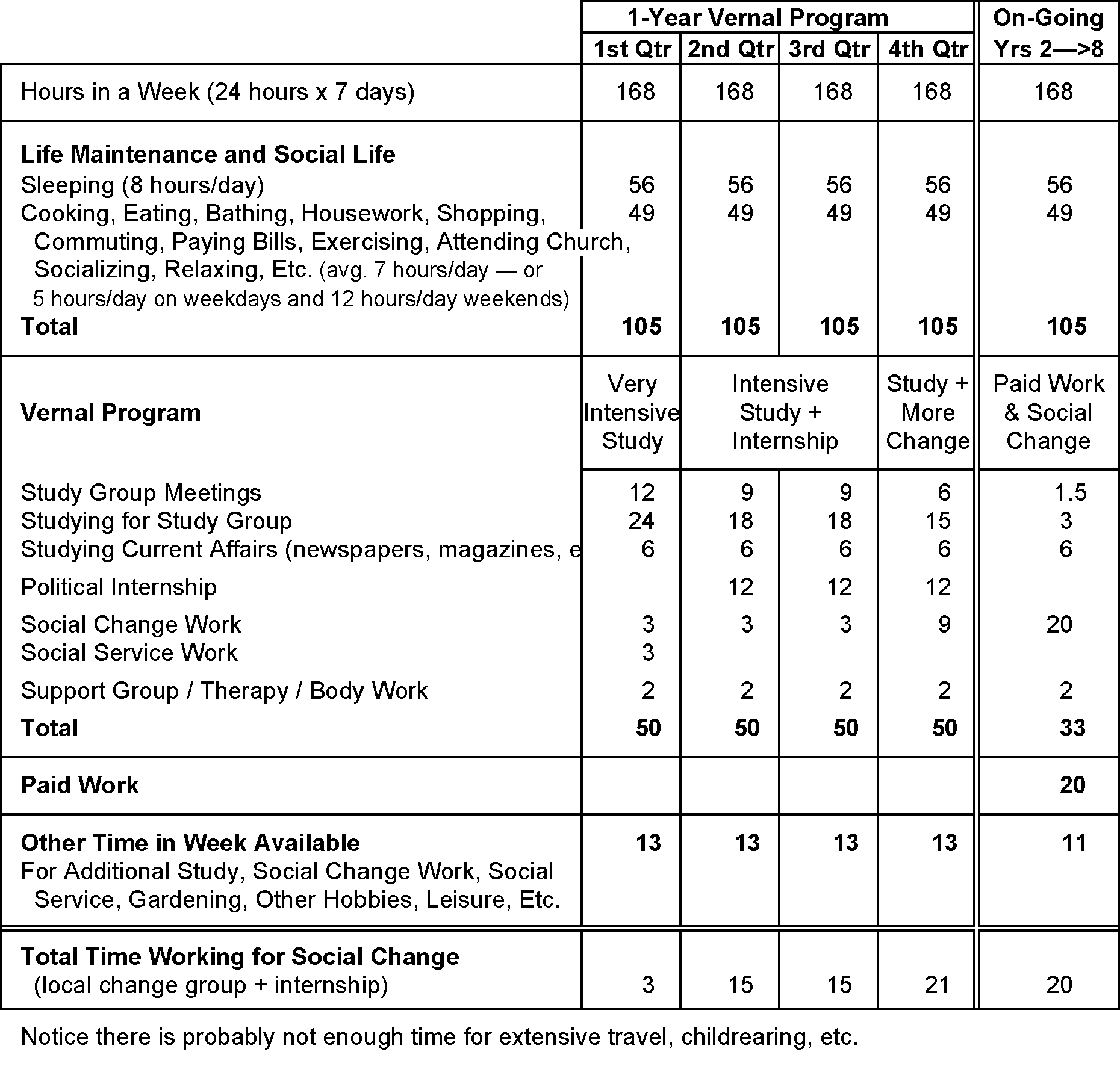

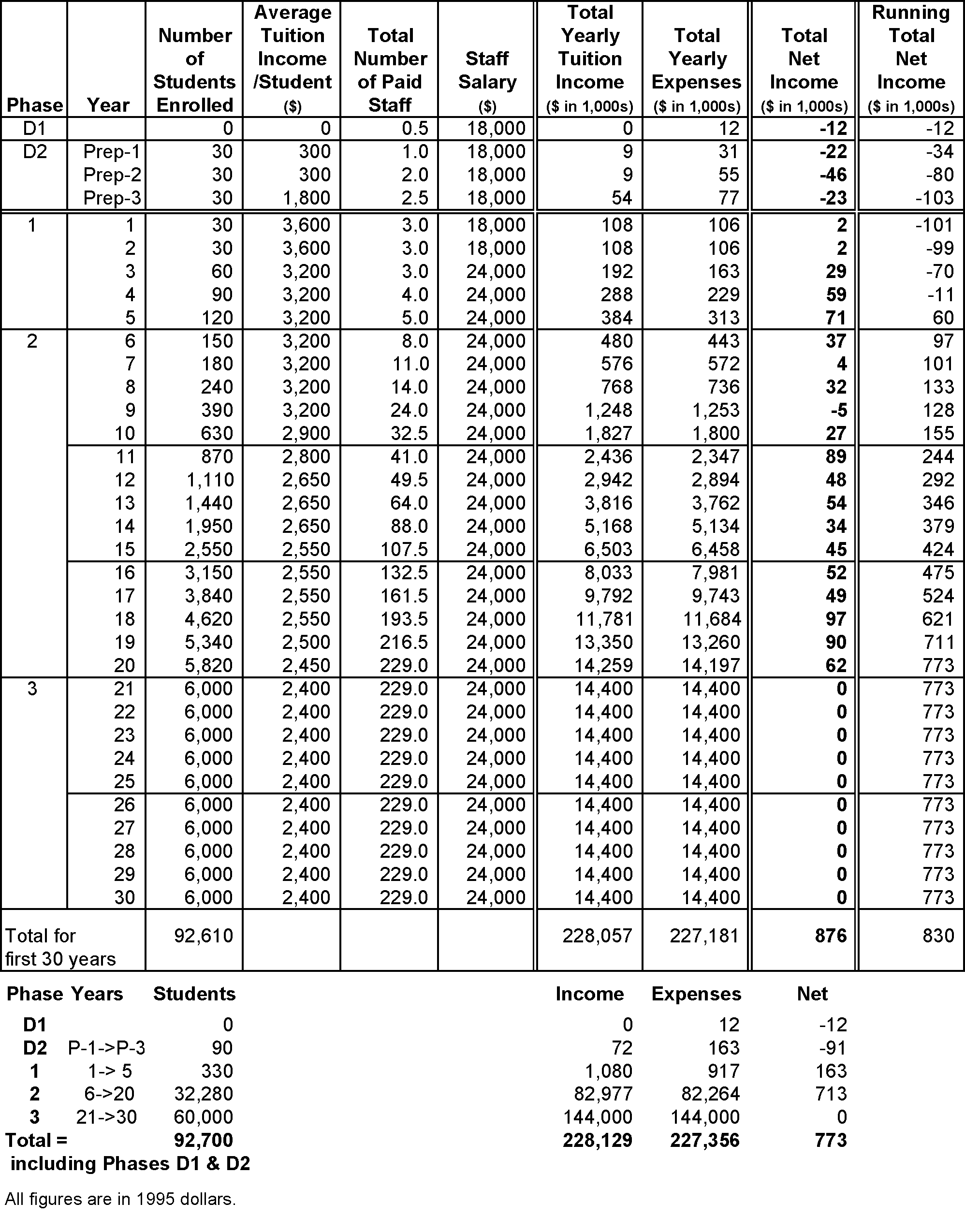

Would there be enough time for Vernal students to fit all these activities into their lives? Figure 6.5 shows how a typical student might spend her time each week of the Vernal session (excluding the weeks spent attending workshops).* Throughout the session, students would devote about fifty hours each week to Vernal activities — with this time allocated in somewhat different ways during each of the four quarters of the year.

* Figure B.3 in Appendix B shows an even more detailed week-by-week analysis of time spent in each of these categories including time spent in workshops, time spent studying for the workshops, and the week-long vacation periods at the end of each quarter. Holidays are not shown, but Vernal students would, of course, observe all the major ones — this would reduce the total hours. Overall, students would devote about 2,300 hours to the Vernal Education Program over the course of the year.

[Picture of Figure 6.5]

Figure 6.5: A Vernal Student’s Typical Week

(when not attending workshops)

As I imagine it, during the first three months (the first quarter), students would spend twelve hours each week meeting with their study groups. They would spend another twenty-four hours each week studying and otherwise preparing for their study group meetings. Students would spend six hours each week reading about current events. They would spend three hours each week working with their social change group and three more hours performing social service. They would also spend two hours per week meeting with an emotional support group or with a personal therapist (or engaging in some other similar activity). During this first quarter, they would devote most of their fifty hours each week to reading and discussing social change information.

For the next six months, students would meet with their study group less often and do no social service work. Instead, they would spend these twelve hours per week in internships. During the last three months, they would meet with their study group even less often and spend these six hours per week working with their local social change group.

I assume that basic life maintenance activities like sleeping, eating, bathing, cooking, shopping, exercising, relaxing, commuting to meetings and internships, and so on would take about 15 hours per day or 105 hours per week. Based on these figures, Figure 6.6 shows what a typical student’s week in the third quarter of the session might be like. This is a busy and full schedule, but should not be overly stressful.

[Picture of Figure 6.6]Figure 6.6: Laura’s Week — Representative of Vernal Students During the Second Quarter

The last column of Figure 6.5 shows how Vernal graduates might spend their time during their seven years of intensive activism after they graduate. Here I assume they work twenty hours each week doing unpaid social change work and another twenty hours each week at an income-producing job. They continue to read progressive publications and get emotional support for the same number of hours they spent during the Vernal session. They also continue to meet with a study group, but only once every other week and they spend much less time preparing for it.

As outlined here, this lifestyle is intensive. There is not much time for activities other than education and social change. Students generally only have about thirteen hours per week for other activities and graduates only have about ten or eleven hours per week. This would probably be enough time for socializing and simple hobbies, but not enough time for extensive travel, childrearing, or other time-intensive activities.

Although this lifestyle would be somewhat limited, it should also be quite fulfilling. Based on my own experience and what I have seen of other activists, I believe many Vernal activists could live this way without becoming weary or disgruntled for eight years (one year as students plus seven more years as very active graduates). I believe they could willingly embrace such an eight-year period of intensive education and social change work since this would comprise only about ten percent of their lives — they would still have time for many other activities in the rest of their lives.

A Possible Vernal Curriculum

It is important for progressive activists to learn about a variety of specific topics. But it is equally important — if not more so — for them to learn how and where to get information, how to learn, how to think, how to wrestle with ideas, and how to debate ideas productively with other people. As I envision it, the Vernal Education Program would devote at least as much time to these important learning processes as it would to offering specific information.

This section first describes a possible curriculum in terms of general areas of knowledge covered, then specific topics that might be covered in the study groups and workshop classes. Finally, it covers the educational methods the Vernal staffmembers would probably use to help students learn to wrestle with diverse ideas and perspectives.

General Areas of Knowledge

There are a zillion things that are useful for progressive social change activists to learn, and they cannot all be learned in just one year. However, certain basic areas of knowledge seem essential:

• Current Reality

How does the world function? What is the conventional way to view social, cultural, political, military, and business affairs? What criticisms do conventional groups have of society?

• Alternative Perspectives

What criticisms do progressive activists have of current society? What are their alternative visions?

The Ignorant know nothing. The Provincial know only the perspective of their own community. Traditionalists hear new ideas, but cling to those of their ancestors. Conformists learn of alternative perspectives, but embrace only the most conventional. Zealots know of other ideas, but accept only what they already believe. The Confused stumble across many perspectives, but don’t know what to believe. It is only the Explorers, the Curious Students, the Free-thinkers, the Scholars who seek out many perspectives and thoroughly investigate each one to dig out its truth.

• Multiple Perspectives

Why do people disagree? Why does each group believe its way is best? What criticism does each group have of every other perspective? What problem does each group’s solution solve and how does it solve it? What are the values and assumptions behind each group’s perspective? What material conditions or philosophical values underlie each group’s perspective? How do you decide who is right?

Until you can see the truth in at least three sides of an issue, you probably don’t understand it. And until you can convincingly argue all three perspectives, you probably can’t work with a diverse group of people to find a mutually satisfactory solution.

• Bringing About Change

How have activists tried to bring about change in the past? What was effective and what was not? Who opposes progressive change and why? What are the methods usually proposed to bring about social change? How do you design an effective campaign for fundamental social change? What factors make success more likely? How do you sustain yourself and others through a long, difficult campaign? What empowers and inspires others to action?

Below I have outlined a possible preliminary curriculum that covers these basics from a multiplicity of perspectives. This curriculum is only an example — staffmembers and students would develop the actual curriculum, and it would evolve over time.

Study Group Topics

Following the schedule of study groups outlined above, students would spend two weeks on each of fourteen topics and a single week on another topic. These topics would cover a variety of social change issue areas and a wide range of theoretical and practical aspects of social change. Each topic would have a list of twenty to thirty different sets of staffmember-chosen readings from which students could choose. Students could also find their own readings. These fifteen main topics might be:

- The Environment

-

- Natural systems

- Consuming natural resources (mining, drilling, logging, ranching, farming, hunting)

- Renewable resources

- Land development

- Population growth, sustainability

- Pollution, garbage, toxic wastes

- Economics

-

- Self-sufficiency, individualism

- Agriculture

- Producing goods, providing services to others

- Ownership, property

- Wealth distribution

- Feudalism, slavery, capitalism, socialism, privatization

- Government regulation

- Transnational corporations, globalization

- Cooperatives, worker-, community-, or government-controlled businesses, locally owned and controlled businesses, non-profit businesses

- Wages, working conditions, occupational safety

- Unemployment, poverty

- Taxes

- U.S. International Relations

-

- Colonialism, domination

- Armed military force

- Diplomacy

- Citizen exchanges

- Global communication

- Social Institutions

-

- Schools

- Churches

- Libraries

- Police

- Prisons

- The military

- The healthcare system

- The welfare system

- Community organizations

- Culture

-

- Education

- Religion, spirituality

- Entertainment

- Sports

- Mass media, the Internet

- Personal communication

- Ethnicity, racism, sexism, classism, ageism, homophobia, and so on

- Personal Relationships

-

- Family, childrearing

- Paternalism

- Battering, dysfunctional families

- Sexual abuse, rape

- Health and healing

- Emotional counseling therapy

- Cooperation

- Feminism

- Sex, hetero- and homosexuality

- Politics

-

- Democracy

- Elections, voting

- Theory of government, anarchism

- Libertarian pluralism

- The U.S. governmental system of making and enforcing laws

- History of Movements for Progressive Change

-

- Anti-slavery

- Populist

- Socialist (1910s and ’20s)

- Conservation (National Parks)

- Women’s suffrage

- Labor union

- Consumer

- Conscientious objectors to war

- Black freedom struggle

- Anti-Vietnam war

- Anti-nuclear power and weapons

- Environmental

- Women’s liberation

- Anti-racism

- Gay and lesbian freedom

- Anti-globalization

- Other movements around the world

- Visions of a Better Society

-

- Utopian visions

- Nonviolence

- Participatory democracy, citizenship

- Appropriate technology, simple living

- Multiculturalism

- Cooperation, community

- Theory and Practice of Social Change

-

- Analyzing power structures

- Choosing issues

- Strategic planning

- Stages of a movement

- Political, social, and cultural change

- Movement Building

-

- Developing visions of a good society

- Researching an issue

- Educating and persuading others

- Lobbying

- Lawsuits

- Campaigns for political office

- Demonstrations, struggling for change

- Designing effective campaigns

- Organizational Development

-

- Starting and developing an organization

- Recruiting volunteers

- Supporting and empowering people, team building

- Facilitating meetings

- Addressing racism, sexism, and so on

- Resolving conflicts

- Fundraising

- Administration

Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.

- Being an Activist

-

- Personal growth and emotional therapy

- Critical thinking

- Internalized oppression and liberation

- Building a supportive community

- Personal finances

- Repression of Activists

-

- Spy and intelligence agencies

- Police, red squads, FBI

- National Guard, Marine Corps

- Private security agencies

- Death squads, Ku Klux Klan, other terror groups

- Public relations firms

- Movement-breaking consultants

- Honesty, trust

- Building a safe community

- Teaching Others

-

- Theories of adult education

- Teaching styles

- Mentoring activists

- Developing curricula

Workshop Class Topics

As I see it, the eighty workshop classes (each two and one-half hours long) would cover many of the same topics as listed above, but would focus on aspects that are more easily learned through workshop presentations and experiential exercises than through reading and discussion. Below is a possible list of topics. The numbers in parentheses indicate how many classes might be devoted to each topic. Note that topics are listed in logical categories. However, classes would probably not be conducted in this order but in an order that matched the study group schedule, students’ needs, or staffmembers’ schedules.

- Choosing One’s Values (4)

-

- Personal change, social change, and values clarification, developing a vision of a good society (1)

- Becoming informed — newspapers, magazines, radio, TV, the Internet, and other news and communication media (1)

- Deciphering and overcoming media propaganda (1)

- Appreciating other perspectives and developing truths to live by — creating, testing, and challenging models of reality, thinking clearly, debating different perspectives, critical argumentation (1)

- Being an Activist (12)

-

- Self-esteem and assertiveness — being bold and nonviolent (1)

- Internalized oppression and liberation (2)

- Emotional and physical sustenance in tough times (1)

- Building a supportive community — daily interaction, concern, support, humor, singing, massage (2)

- A range of counseling therapy and personal growth techniques (1)

- Living lightly on the earth every day (1)

- The many roles of an activist — rebel, citizen, reformer, social changer, scholar, manager, facilitator, worker, secretary, counselor, minister, spokesperson, teacher (1)

- Personal finances — toward financial independence (1)

- Money and class on a personal level (2)

- Developing a Social Change Organization (15)

-

- Starting and developing a social change group (1)

- Organizational forms and structures (1)

- Discussing, debating, and struggling with ideas (1)

- Encouraging diversity and dissent, avoiding groupthink, mind-control, and cult-like behavior (1)

- Addressing racism, sexism, homophobia, ageism, and other prejudices (2)

- Addressing classism and money issues (2)

- Dealing with emotional trauma and craziness — emotional support (2)

- Resolving conflicts (2)

- Dealing with infiltration, provocateurs, harassment (1)

- Helping other activists learn new skills (2)

- Meeting Together and Making Decisions (7)

-

- Leadership and management theories (1)

- Parliamentary procedure and voting (1)

- Making cooperative decisions (1)

- Facilitating a group meeting (2)

- Effective problem solving in groups (1)

- Working in large, dispersed organizations (1)

- Running a Social Change Office (4)

-

- Basic office management skills — filing, accounting, communication, computer use (2)

- Basic organization maintenance skills — fundraising, membership, personnel management (2)

- Social Change Methods (17)

-

- Researching an issue (1)

- Developing visions of alternatives (1)

- Writing, publishing, and distributing leaflets, pamphlets, newspapers, books, and web pages (1)

- Persuasion techniques and methods (1)

- Speaking out publicly (1)

- Canvassing (1)

- Outreach to the news media (1)

- Political film and video (1)

- Political music, art, and theater (1)

- Protest demonstrations — rallies, vigils, fasts, pickets, marches, confrontations (1)

- Strikes and boycotts (1)

- Civil disobedience and direct action (2)

- Risking arrest and going to jail for a cause (1)

- Electoral politics and lobbying (2)

- Lawsuits, referenda, and other legal action (1)

- Social Change Campaigns (6)

-

- Strategic planning for social change — force field analysis (2)

- Designing effective campaigns — constituencies, issues, and action (2)

- Campaign simulation (2)

- Working with Others (7)

-

- Addressing special constituencies — racial/ethnic minorities, religious groups, elders, young people, labor union members, lesbians and gays, women, rural folks, and so on (3)

- The diversity of social change groups — their ideas and practices (2)

- Working in coalitions and federations (1)

- Local grassroots groups and how they relate to national social change organizations (1)

- Social Change Movements (3)

-

- Types of change movements and their goals: resistance, liberation, democracy, and stewardship (1)

- Evaluating and choosing ten important areas of focus for social change in the next few decades (2)

- History of Social Change Movements (4)

-

- Overview of world movements for change (1)

- Oral history of recent local movements presented by active participants (2)

- Lessons we can learn from earlier social change efforts (1)

Reading Lists

Vernal staffmembers, working in conjunction with students, would continually revise the list of reading materials for study groups, adding new books and articles and retiring weak and outdated materials. They would also maintain a library of all these materials to loan to students.

The Vernal Education Program Curriculum Checklist:

- Why are we studying this?

- Why are we using these methods?

- Is there a more educational or empowering way?

Workshop Notes and Agendas

Vernal staffmembers would also prepare detailed workshop notes on the topics outlined above. Generally, for each topic, the notes would include major points of interest and discussion, the range of perspectives held by progressive activists (and others), active areas of contention and debate, and references to books, articles, web pages, and other sources of information. They would also include lists of questions and discussion topics to challenge and stimulate students to learn and explore new ideas. They might include provocative quotations or koans (paradoxical Zen Buddhist riddles to ponder in order to attain intuitive knowledge). For some topics, the notes might simply be annotated bibliographies of important books, articles, and web pages. Some notes might include a sample workshop agenda.

The notes would give students more information than they could absorb in workshop classes. After graduating, Vernal activists could review the notes when they were actually faced with difficult situations in their change work. Graduates could also use the notes and agendas to develop evening or weekend workshops for other activists, and when appropriate, they could pass copies of the notes to others. Moreover, these notes would be broadly distributed outside of activist circles — posted on the Vernal Project website http://www.vernalproject.org — to help advance social change more widely. “Information is power,” and these short, clear, and understandable summaries of progressive change theory and practice could be very powerful.[4]

Researching and Developing the Curriculum

With help from students, Vernal staffmembers would continually update the curriculum, incorporating new social change issues, new social change methods, and new change philosophies. They would draw on magazine articles, books, web pages, their own social change experience, and the experiences of other activists.[5] Vernal staffmembers would share their research and coordinate the development of new curricula with other Vernal teams around the country.

Educational Methods and Style

The curriculum of the Vernal Program would be very important, but the way that it was presented would be just as important — students learn as much by watching their teachers and mentors as they do from studying. I expect that the Vernal Program would refrain from using the cruel and disempowering techniques common in many traditional schools.

What you are speaks so loudly I can’t hear what you say.

Though public and church schools have the admirable goal of educating children, they also usually have a more sinister goal: to mold students so they will conform to societal norms and accommodate themselves to the ruling authorities. To accomplish this unsavory goal, schools usually employ four main processes:

• Selective information

Schools present a limited amount of information, usually from a narrow spectrum of perspectives and declare “this is the way it is.” If mentioned at all, alternative ideas are usually explained badly and belittled. Standardized textbooks ensure that everyone receives the same one-sided information.

• Indoctrination

Schools repeatedly present the same information as fact until “the Truth” seems self-evident and all other ideas seem ludicrous.

• Manipulation

Schools use grading and tracking to control and steer students into acceptance of the status quo. Those who best adopt conventional dogma are encouraged and rewarded; those who do not are held back, criticized, and even ostracized.

• Demoralization

Students are controlled and restricted. They are forced to attend (often boring) lectures. This steals their initiative and demoralizes them.

Social change schools teach a more progressive ideology, but some actually employ the same mind-numbing and manipulative teaching processes as conventional schools. As I see it, the Vernal Program would empower students to explore a variety of ideas and develop their own ideology by using these alternative methods:

• Comprehensive Information, Diverse Perspectives

The Vernal Program would present a wide array of information and perspectives including age-old wisdom, conventional thought, and a range of alternative perspectives: “Here’s what different people think and their reasons for thinking it.”

• Questioning

Take from others what you want, but never be a disciple of anyone.

The Vernal Program would encourage questioning: “How do we know this is true? How do we find out? How else do people look at things? Why do some people disagree? Whom can we believe? Are there other ways of looking at an issue that no one has ever considered?”

• Discussion and Problem Solving

The Vernal Program would show students how to gently and productively discuss divisive topics and resolve conflicts by clearly summarizing all perspectives, sorting ideas into categories, and synthesizing new, more comprehensive perspectives.

• Scientific Method

The Vernal program would encourage students to ascertain truth by evaluating evidence — not to accept dogma based on blind faith. “What works? What doesn’t? What is useful? What might work better? How can we test this? Do our hypotheses seem to predict future events accurately? If not, what new postulate can we test that might predict it better? Which entities and postulates seem useless and can be discarded?”

An ideology that cannot withstand intense challenge is invariably anti-progressive. Through questioning, ideas grow to be more robust and compelling. Question Authority!

• Open Education, Collegial Atmosphere

The Vernal Program would have no requirements for participation in any activities. Students would not be graded, and every student who completed the session would receive a diploma. Staffmembers would assist students to learn whatever the students thought was best for themselves (within the constraints of the overall Vernal Program). Staffmembers would strive to maintain their role as helpful resource people rather than as leaders or controllers of students.

Students would be encouraged to collaborate with, help, and teach each other — passing on what they had learned through their years of experience or what they just learned the day before. Staffmembers would also ask students to help them to evaluate and modify the curriculum, materials, and educational methods.

The Vernal Program would in no way be value-free — the curriculum would clearly be quite progressive and the staffmembers’ various progressive views would permeate the program. But as much as possible, when staffmembers expressed their perspectives, they would try to make their ideological bent explicit, allow it to be discussed, and encourage it to be challenged.

The true teacher defends his pupils against his own personal influence.

• Humane, Gentle Struggle

The Vernal Program would also encourage staffmembers and students to acknowledge that they are each human beings with feelings, desires, and limitations. The program would encourage them to respect their differences and to treat each other well even as they struggled over ideas.

Vernal Staffmembers

Background and Skills

Vernal staffmembers would be chosen for their experience as social change activists and for their educational skills, especially their ability to use alternative, student-centered education methods. When hiring new staffmembers, existing staffmembers would try to recruit people with whom they could easily work. They would also seek demographic and ideological diversity.

Each staffmember in a Vernal team would have similar responsibilities, differing according to need and according to each staffmember’s interests. Those with more experience and skill in education might focus more on facilitating workshops; those with more administrative skill might work more on setting up internships, handling finances, and hiring. Optimally, every staffmember would be skilled in all the areas required for educating students and administering the program. More likely, though, staffmembers of each Vernal team would have complementary skills that could address everything necessary.

Staff Hiring and Pay

Given all that would be expected of them, staffmembers would likely work quite hard. The work should be rewarding, but the amount of it might still be exhausting. Since staffmembers would be experienced and skilled in many areas, disgruntled staffmembers could probably find other lucrative jobs without much effort. In order to induce staffmembers to work for years without burning out or leaving, they would need to be paid reasonable wages and benefits. On the other hand, wages could not be too generous or the cost would threaten the overall viability of the Vernal Project.

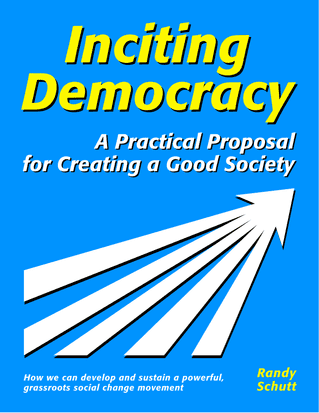

Aiming for a prudent balance, I assume the Vernal Program would pay full-time Vernal staffmembers $24,000 per year (in 1995 dollars) and offer generous benefits that included paid vacation, holidays, and health and dental care coverage.[6] In addition, the Vernal Program would put $2,000 per year into a retirement account for each staffmember. Part-time staffmembers would earn a proportional share of salary and benefits.

Dedicated Vernal staffmembers with few obligations should be able to live reasonably well on this salary. However, it would probably be too small an amount for staffmembers to support a spouse and children or for them to save much during their tenure. Still, I expect many activists would be eager to work as Vernal staffmembers since the work would be quite satisfying and the organization would be very supportive.

Hiring and integrating new staffmembers would require a great deal of effort, so people would be hired who planned to stay with the Vernal center for at least five years. But staffmembers who stayed too long could become stale and stodgy, so they might be encouraged to move on to other endeavors after ten or fifteen years. Staffmembers would be evaluated each year by their peers and the local center’s board of directors (see below).

Vernal Students

Admission Requirements

The main purpose of the Vernal Project would be to bring about fundamental progressive transformation of society. However, it is possible that over time the Vernal Program might be seen as a surrogate business school by those seeking an inexpensive entrance to the executive ranks of corporate America or as an inviting intellectual sandbox for those seeking an inexpensive place to play with philosophical ideas.

Admissions must therefore be quite selective to ensure that the limited resources of the Vernal Project would be used wisely. The program must be available only to those most open to learning and most interested in using what they learn to work for progressive change. These would be the minimum requirements:

• One-Year of Experience with Active Social Change Work

It would be important that applicants already have some activist experience so they would know the joys and disappointments of working for change and how this work affected them. After doing it for a while, many activists discover that social change work frustrates, bores, or frightens them. Other activists realize that other activities are more important to them, at least at that particular point in their lives.

After a year of social change work, applicants should have a good sense of what social change work is all about, and they could knowledgeably decide if they wanted to work long-term for fundamental change. In addition, by having at least a year of experience, students would have a much better idea of what they needed or wanted to learn. Moreover, they would have accumulated some valuable experience to share with other students.

• Academically Capable

The Vernal Program, as I envision it, would be similar to college, requiring extensive reading and studying. Students would need to handle a fairly heavy academic workload. Many people do not enjoy this kind of academic work and the Vernal Program would be inappropriate for them. Non-academically oriented activists would probably learn better with an activist mentor who could assist and guide them “on the job.”

• Willing and Able to Work Primarily for Fundamental Social Change for Eight Years

Applicants would have to seriously intend to make social change work their highest priority for eight years (one year in the Vernal session plus seven years after graduating). During this eight-year period, they would be expected to work at least twenty hours per week for fundamental change. They must also be willing to work to end their own oppressive and addictive behaviors, support and encourage other nonviolent activists, and as much as possible, serve as a good role model for others by living in an exemplary way.

By making fundamental change their highest priority, Vernal activists might be forced to delay for eight years many of the pleasures and activities of their peers: partying nightly, traveling, raising children, pursuing a conventional career, saving money for a house and retirement, and so on. Older activists who had already done most of these things might find it easier to make this commitment, though some might have a difficult time adjusting after years of a more conventional lifestyle.

Respectable men and women content with good and easy living are missing some of the most important things in life. Unless you give yourself to some great cause you haven’t even begun to live.

Also, since social change work usually pays little or nothing, Vernal students and graduates would likely need to live modestly and inexpensively. Since they would probably be able to work no more than half-time at a non-social change job or full-time at a change job, most could probably earn only $10,000 to $30,000 per year. This limitation would probably not be very important for those financially supported by spouses or family members, those living on retirement funds, or those relying on independent wealth. However, those relying only on their earned income would be forced to have a frugal lifestyle: living in shared housing; riding a bicycle, taking public transportation or having an older car; doing without fancy clothes, expensive furniture, and expensive appliances; and so on.

• Oriented Toward Behind-the-Scenes Support of Other Activists

Priority for admission would also be given to applicants who indicated interest in doing the kind of basic support work that the Vernal Program most encourages. Vernal graduates would generally be helpers, facilitators, and supporters — providing leadership from below — rather than designated powerholders or leaders who controlled or directed others.

• Able to Pay Tuition and Support Themselves

Applicants for admission would have to indicate how they would plan to pay Vernal tuition and how they would sustain themselves during the one-year session. The nature of the Vernal Program would probably prevent students from tapping conventional Federal and State education grants or loans. Loans of any kind might be problematic since most Vernal graduates would earn little money.

Some of the students’ internships might pay stipends, and some internally generated scholarships would be available (see below). However, most students would need to tap their savings or rely on their spouse, parents, grown children, friends, or other supporters for financial support. As part of the application procedure, each indigent student would be encouraged to assemble a group of personal supporters who could contribute financially to her education and could then share in the glory of her accomplishments.

• Positive Recommendations

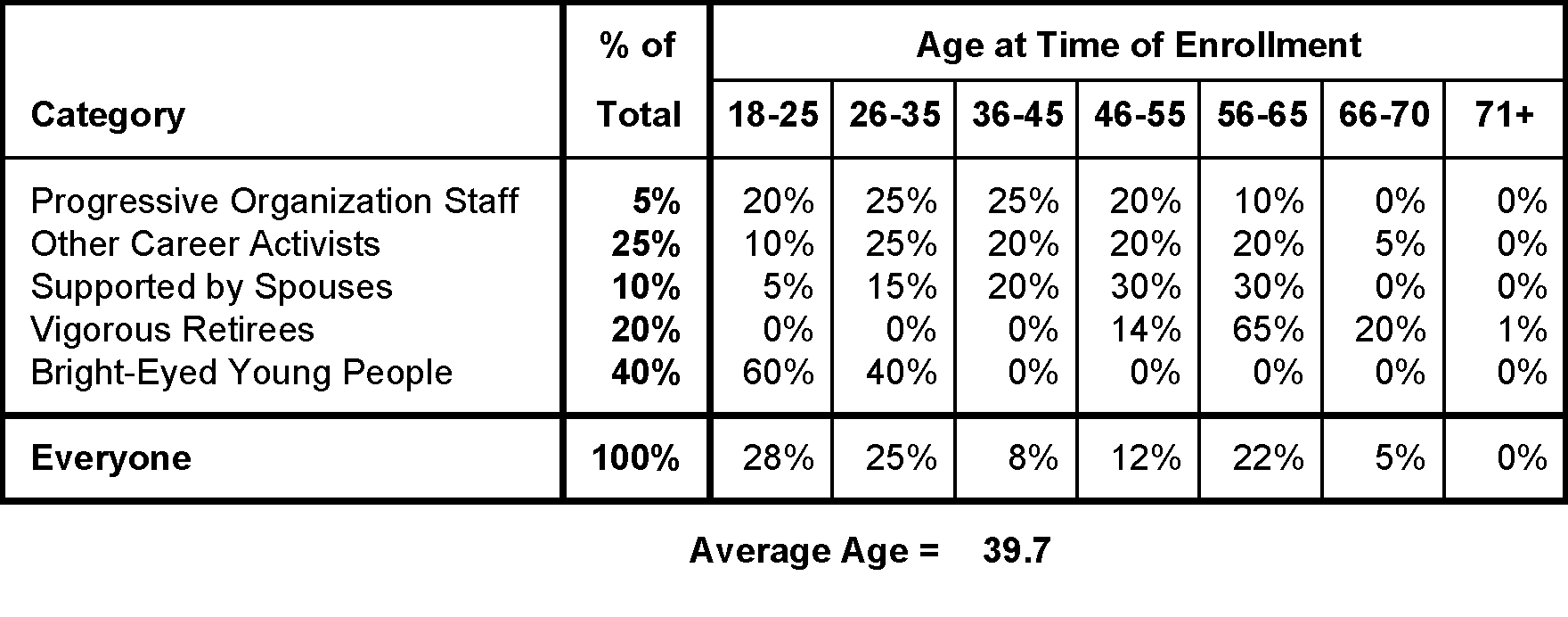

Applicants would need to have very positive written recommendations from three activists, professors, clergypeople, or others who knew them well and could honestly evaluate how well they work as progressive social change activists.